One man’s meat is another man’s poison, or so goes the ancient Roman adage. It’s a premise that the upcoming Disgusting Food Museum in Sweden was designed to explore.

Take haggis as an example. Many who have tried Scotland’s national dish – made from sheep heart, liver and lungs and traditionally cooked inside the animal’s stomach – think it’s delicious. Yet it is one of the 80 food exhibits at the museum because a lot of people, mainly those who have only heard about it, think it’s repugnant.

The same goes for the other exhibits, some of which include sheep eyeballs in tomato juice (a Mongolian cure for headaches); century eggs from China aged until the yolks are cheesy and the whites are jelly; spicy rabbit heads, complete with eyeballs, tongue and a pate-like brain; natto (bacteria-fermented soybeans from Japan), Greeland’s kivak (little auk birds stuffed in a disemboweled seal); and kopi luwak (or cat-poop) coffee. All are “real foods eaten today or of great historical significance somewhere in the world”.

According to founder Samuel West: “Disgust is individual - the thought of eating a spider makes some people hungry, but makes others want to vomit. It is contextual - many consider milk from a cow less disgusting than fresh milk from a lactating human friend. And disgust is cultural – we [tend to] like the foods we have grown up with.”

But he says that ideas of disgust can change with time. Two hundred years ago, lobster was so undesirable that it was only fed to prisoners and slaves. Today it is a delicacy. The museum invites visitors to challenge their notions of what is and what isn’t edible. West also notes that when he first moved to Sweden, he hated salty liquorice, but now he loves it.

On another level, human beings are fascinated with disgust, which is one of the six fundamental human emotions. “Just as a roller coaster offers us a safe experience of danger, we humans are fascinated with disgust from a safe distance. We are intrigued by slimy slugs, gory movies, and watching someone on the verge of vomiting trying to eat something awful. The evolutionary function of disgust is to help us avoid disease and unsafe food, and our ideas of disgust influence our lives in many ways, from our choice of foods to our morals and laws,” says Andreas Ahrens from the museum.

Shock value and philosophical musings aside, West and team also have a more important agenda in place. “Our planet cannot sustain current meat production, and we need to consider alternative protein sources such as insects and lab-grown meat. [Maybe] changing our ideas of disgust help us embrace the environmentally sustainable foods of the future. It could help us transition to more sustainable protein sources,” explains Ahrens.

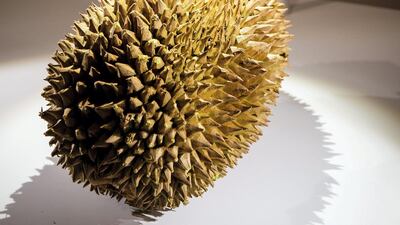

Most of the exhibits are real food, while some are replicas and others are displayed as video. Most of the real foods can be smelt, even Thailand’s durian fruit, which one writer described as “turpentine and onions, garnished with a gym sock”, while a few others are available for tasting should you dare.

Alongside the description that accompanies each item, some come with tasting instructions. For example, a warning for the Casu Marzu (maggot and fly larvae) cheese, which comes from Sardinia in Italy, reads: “Diners need to protect their eyes from jumping larvae, and eating live maggots is risky, as they can survive inside their new host and can bore through intestinal walls.”

The exhibit opens on October 31 in Malmö, Sweden, across the bridge from Copenhagen, Denmark

____________________

Read more:

Could eating insects save the world?

10 delicious dishes to dine on this World Vegetarian Day

Dickey’s BBQ is coming to Abu Dhabi: ‘I have seen grown men struggle to get through our side dishes’

____________________