It all started with a quote from The Voyage Out by novelist Virginia Woolf. It's a passage where, as Olivier Saillard points out in his delicious French accent, "she is describing the man she loves through the pants he threw on the floor". A veritable fashion polymath – historian, artistic director, curator and on the list of the Business of Fashion's most influential people – Saillard is the man behind A Short Novel on Men's Fashion in Florence, Italy.

The exhibition opened at Palazzina della Meridiana on June 12, and includes 110 brands that participated in the runway shows or were featured in special events at the annual Pitti Uomo menswear event between 1989 and 2019. After all, a journey through 30 years of modern menswear inspired by the words of a modernist female writer from 1915 is the perfect inspiration for a fashion retrospective.

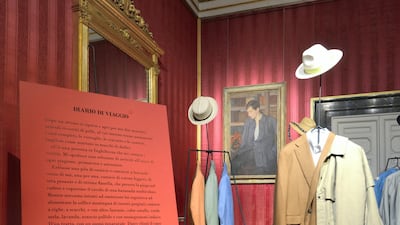

I gained access to the brand-new exhibition accompanied by a special chaperone, curator Saillard himself. Upon entering the baroque halls of the galleries on the second floor of the Museum of Costume and Fashion, it is immediately obvious that this is no ordinary show. For one, there are no mannequins in sight. I remember reading that Saillard doesn't like them, and he confirms this by pointing out that fashion is, literally, "more alive without mannequins".

Instead, many of the outfits appear to be jumping off the pages of oversized, custom-created books bound with decorative ribbon ties. The title of each book – Travel Journals, Journal of a Man and so on – fits with the theme and colours of the room in which it is placed.

The 30-year history of Pitti Immagine and its Discovery Foundation, the organisation that appointed Saillard as artistic consultant in the summer of 2018, is told through the outfits, which were donated by the brands themselves, as well as through men's portraits on loan from the Palazzo Pitti Gallery of Modern Art. They are accompanied with quotes by the likes of Woolf, Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, American author F Scott Fitzgerald, and Italian poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. About the latter, Saillard reveals: "Actually, I'm seeing every movie from Pasolini because we have a good project with Tilda Swinton with the costumes of Pasolini." Incidentally, Saillard first appeared on my fashion radar at Pitti Uomo in 2015 when he and Swinton brought a performance piece titled Cloakroom to the fashion fair.

The items that are on view in the current show, which is running until September 29, will become part of the permanent collection of the museum. A Short Novel on Men's Fashion is also a book, featuring essays by Italian Hearst editor Antonio Mancinelli, Vogue's Suzy Menkes, French fashion journalist Frederic Martin-Bernard and Saillard himself. Both the exhibition and the book are dedicated to Marco Rivetti, who was the president of Pitti Immagine from 1987 to 1995.

Saillard explains that it is meant as an homage to Rivetti’s vision, which was to “create a relationship between culture and men’s fashion”. The vibe felt all around Florence, particularly in the days of Pitti Uomo, is a result of Rivetti’s foresight. I wouldn’t be surprised if this latest effort finally manages to put the city on the fashion map alongside London, Paris, New York and Milan.

A novel display

The exhibition benefits from a dreamlike feel, created by the combination of the fluidity of clothes housed within brocade-wallpapered rooms, hanging from oversized dark steel valets or draped over those giant blank book pages. Frescoes on the ceilings and gilded chandeliers add to the anti-establishment, whimsical sensation that has become Saillard’s trademark, where an 18th-century taffeta suit with silver embroidery sits alongside a Vivienne Westwood maxi cardigan with cutouts, just as easily as jeans go with a T-shirt.

Saillard's aim was to create in the visitor a sense of passion for menswear. Needless to say, he succeeded. When I walk the halls on my own, I feel like I can almost reach over and grab the luscious Brioni golden jacquard jacket from the 1971 collection, put it on and feel like James Bond. In fact, the Brioni atelier was responsible for making some of the suits donned by the British spy as well as for Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni's character, Marcello Rubini, in Federico Fellini's film La Dolce Vita.

And yet, by his own admission, of the 120 or so fashion exhibitions Saillard has helped put together in his 25-year career, only three have been devoted to men's fashion. When I ask why, Saillard explains that "men's fashion is always the enfant pauvre, the poor cousin, compared to women's fashion". He welcomed this challenge because "it's easier to provoke desire, to provoke dreams [by] presenting an evening dress from Christian Dior or Balenciaga, but to present a grey costume, then a black costume, it's not very easy", he says, and consequently, menswear is often termed boring. However, he is quick to add: "Men's fashion is a frame, but within that frame there are endless possibilities."

The man who changed the game

Some of brands on show include Trussardi, Valentino, Romeo Gigli, Antonio Marras, Raf Simons, Brunello Cucinelli, Viktor & Rolf, Burberry, Dries Van Noten, Dior Homme and Giorgio Armani, all of which will become part of the museum’s permanent collection. “You will see a very nice room devoted to Armani and Hedi Slimane because they are the two pillars of men’s fashion,” adds Saillard. While Armani dictated the silhouette in the late 1980s and 1990s, Slimane changed everything at the start of the new millennium when he took over as creative director of Dior Homme.

“Although I don’t always agree with him, I have to say he changed the way of history,” says Salliard, pointing out that “every boy found it interesting to buy, to wear Hedi Slimane, and more or less every boy in Milan or Paris, who is working in a bank is now wearing a costume inspired by him”.

“Costume” is the French word for “suit”, and Saillard’s way of referring to men’s outfits. He alludes often to the “black costume” as a basic, and loves telling the story of an English dandy he once met in the home of Madame Carven, the couturier.

"He had a very nice costume from Savile Row and inside the pocket he had a paper where he would have written the day when he would need to wash the costume," Saillard recalls. "He didn't move too much, this English dandy, so as not to damage or wrinkle his suit. And in the areas where moths had got to the wool, the dandy had embroidered the holes, with the dates of the year. How poetic is that?"

I find myself agreeing. Fashion is a dream, and the fantasy can indeed consist of embroidering over the imperfection in our clothes or finding hidden inspiration within an exhibition such as the one Saillard has so thoughtfully curated.