While some select clothes to project an air of respect or perhaps authority, others wear them to make a stand.

Whether you wave placards at demonstrations or prefer the anonymity of online petitions (my past was limited to badges supporting the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and Nelson Mandela), the outfits we choose – or refuse – to wear are the front we offer the world. Clothes have long been used to denote social rank or group. From the robes worn by kings and the tiny slippers covering a Chinese lady's bound feet, to the leather jackets of the rebellious 1950s teenager, what we wear tells everyone who we are.

Likewise, clothing can also be employed to opposite effect, and to group people in a negative, discriminatory manner. In medieval Europe, striped clothes were thought to be "ungodly", and were used to mark out those considered to be on the lowest rung of society, such as prostitutes, criminals, and hangmen. The Russian emperor Peter the Great viewed beards as backward, so put a tax on them and had men forcibly shaved in the streets. The German Third Reich of the 1930s used attire to devastating effect, dividing society by forcing Jews to wear a yellow star. When the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 1996, one of its first moves was to control women by making wearing the burqa compulsory.

During the 1960s, those that were part of the counterculture movement in the United States grew their hair long and wore loose, flowing clothes in opposition to the rigid uniforms of the US military and, by extension, the Vietnam War. African Americans adopted the dashiki – a traditional piece of clothing from West Africa – as a reclamation of stolen heritage.

Today, it seems that there is a crackle of political tension in the air once more. As western culture is being rocked by scandals across the Hollywood film industry, the Catholic Church, governments and even the president of the United States, it is no surprise that people feel the need to express their displeasure.

When Maria Grazia Chiuri took over at the house of Christian Dior in 2017, the first woman to do so, she opened her debut spring/summer show with a T-shirt that read: "We should all be feminists". Inspired by the book of that name by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Chiuri seemed to plug into an awakening of social conscience, as her models wore black berets reminiscent of the Black Panthers of the 1960s in the finale.

The next season, a swathe of labels followed Chiuri's lead, such as at Prabul Gurung with T-shirts emblazoned with "The future is female" and "This is what a feminist looks like", while Public School took a sassier tone with "Feminist A.F". Designer Ashish Gupta seemed to take a swipe at Donald Trump's fondness for social media with a top that read: "More glitter, less Twitter". Missoni, not to be outdone, decided to forego the slogan tee altogether, and had its models wear pussy hats.

For autumn/winter 2018, Dior stayed with a message of revolt, with Chiuri using French students of the 1960s as her inspiration, while in London, veteran agent provocateur Vivienne Westwood took to the runway for her autumn/winter 2018 show wearing a "Climate Revolution" T-shirt.

Of course, the slogan tee is nothing new for Westwood who, as part of the punk movement of the 1970s, had tops covered in words such as "Destroy". In 2005, she created T-shirts that read: "I am not a terrorist, please don't shoot me" – photographed on a baby, while in 1989, she was the cover star of Tatler, dressed as British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, under the headline: "This woman was once a punk". The stunt brought Westwood infamy and cost the magazine editor her job.

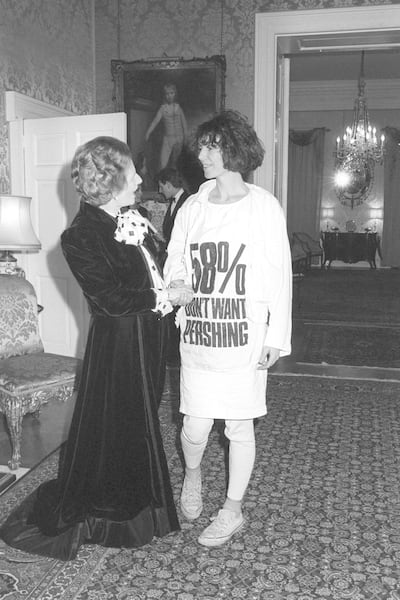

Perhaps inspired by the early punk days of Westwood, in 1984 fashion designer Katharine Hamnett put politics on the front page when she met Thatcher while wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with “58% don’t want Pershing”, in protest against the introduction of the US’s Pershing II missile to Europe.

Her simple execution of large, easy-to-read letters on a plain white background had many copycats, including the band Frankie Goes to Hollywood, who the same year, when told their debut single was banned for inappropriate content, printed T-shirts that read: “Frankie says relax”. Simple yet provocative, those garments helped make the song, despite not being played on television or radio, the UK’s seventh bestselling single of all time.

Yet clothes can provoke in more subtle ways. In 1997, when Princess Diana stepped into an Angolan minefield, she displayed not only courage, but also a deep understanding that the sight of her – then the most famous woman on the planet – dressed in body armour and a head protector, would gather more attention than any number of written articles. Such silent protest was seen more recently, when a young woman named Ieshia Evans was photographed being arrested in Baton Rouge in Louisiana, in July 2016.

At a Black Lives Matter protest, Evans was immortalised in a photograph of her standing calmly as two heavily armed officers rushed towards her. While the officers are dressed for a riot, in full armour and visors. Evans, in contrast, is wearing a summer dress. Just as the officers look menacing and imposing, the intention of such a uniform, Evans looks vulnerable, like a butterfly that could be crushed in one hand.

The US witnessed another show of passive resistance a few months later when, on January 20, 2017, Donald Trump was inaugurated as president. Despite Trump having boasted on television of sexually assaulting women, many were upset he had not been held to account, triggering the Women's March the day after he took office. With an estimated crowd of more than one million compared to the estimated 600,000 at the inauguration, the striking thing was that many in the crowd wore pink pussy hats. The brainchild of Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman, following the US election the previous November – with a name taken from Trump's description of assaulting women – the idea was to unite supporters, who were all wearing the hand-knitted pink hat.

Although no figures exist for how many hats were worn across the subsequent 600 events attended by 4.2 million people, many are clearly visible in the documenting photographs. Such was the power of the pussy hat, which even appeared on the cover of Time magazine in March 2017.

By October 2017, America was rocked again by tales of exploit when the Harvey Weinstein sexual assault scandal broke, triggering a bout of soul-searching across Hollywood and the film industry. With the hashtag #MeToo for victims to speak up, it had the unexpected effect of prompting the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, the national farmworkers alliance, to publish an open letter asking that poor farm and factory workers who faced sexual exploitation not be forgotten.

Perhaps shocked at the scale of abuse facing women, Shonda Rhimes, Natalie Portman, Ashley Judd and America Ferrera were galvanised to create the Times Up campaign and, most crucially, establish funds to help women fight sexual predation in the workplace. Keen to bolster support, a request was made that those at the Golden Globes Awards held in January 2018 adhere to an all-black dress code. In a remarkable show of strength, the likes of Penelope Cruz, Margot Robbie, Nicole Kidman, Jessica Biel and Angelina Jolie all walked the red carpet in head-to-toe black, as did men such as Chris Hemsworth and Ewan McGregor.

A few weeks later, the Times Up team asked that those attending the Grammys wear white, or carry a white rose, resulting in Lady Gaga, Heidi Klum, Miley Cyrus and Zayn Malik turning up with white roses in hand. Singer Lorde went one better and wore the words of American artist Jenny Holzer as a sign on the back of her dress, which read: “Our times are intolerable. Take courage, for the worst is a harbinger of the best. Only dire circumstance can precipitate the overthrow of oppressors”.

Most recently, at the Academy Awards in Los Angeles, many turned up wearing Times Up badges, but possibly the most revolutionary moment was not on the red carpet, but the stage when Tiffany Haddish and Maya Rudolph shuffled on wearing comfy slippers, carrying high heels in hands. With women in Hollywood routinely expected to wear dresses that – though beautiful – are difficult to walk or sit in, jewellery that pulls at earlobes and weighs down necks, and shoes that crush toes (with some actresses resorting to injecting feet with Botox to numb the pain), for two prominent women to joke about what women normally suffer in silence, and on such a big stage, was an eye-opening moment.

Usually Hollywood actresses are required to wear vertiginous heels and dresses held together with sheer will power, while smiling and being charming. A wardrobe malfunction makes a woman memorable for all the wrong reasons, and heaven forgive any female who slips, trips or falls – except Jennifer Lawrence, who has turned tripping up stairs into a signature move. Faced with this, for a woman to declare she will no longer do it, is a brave move in a town where red-carpet dressing is part of the job. Perhaps now, in the aftermath of all the scandals and the social reappraisal taking place on the runways, finally women might be in a position to choose.

___________________

Read more:

With more fashion brands declaring themselves fur free, what's next for the fur industry?

The power of modern protest ... writ large on a T-shirt

The fashionable face of female empowerment: #MeToo at NYFW

___________________

Hollywood may be grabbing all the headlines, however, a much quieter uprising has been taking place in Iran. Since December, more than 30 women have been arrested for removing their headscarves in public, in defiance of the law. Unlike many other countries, the wearing of the headscarf is a legal requirement in Iran, and when Vida Movahed, better known as the Girl of Enghelab Street, took off her scarf in Tehran and waved it on a stick, she was arrested. Other women followed and were also arrested, and while most have been released on bail, one as-yet-unnamed woman was sentenced in early March to two years in jail as punishment for encouraging "corruption through the removal of the hijab in public".

While it may feel as if the Hollywood protests are mundane in comparison, it does seem, seen as a wider picture, that there is a groundswell of support for change. Whether big or small is clearly up to the individual; however, it does seem to appear that now, more so than ever, it is time to wear our hearts on our sleeves.