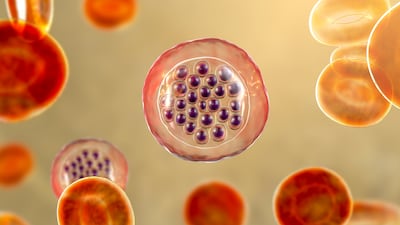

Some people living in ancient Eastern Arabia developed resistance to malaria about 5,000 years ago, a study has found.

The adaptation is believed to have coincided with the introduction of agriculture in the region, a period that possibly fostered conditions conducive for the spread of malaria.

The study, led by Dr Rui Martiniano from Liverpool John Moores University, delved into the DNA analysis of the remains of four people from the Tylos period in Bahrain, who lived between 300BC and 600AD.

This mutation, called G6PD, is most prevalently observed in the UAE, hinting at a long-standing genetic adaptation within the populations of this area.

“Most of what we know about this variant derives from genetic studies of present-day populations and, therefore, the distribution and spread of this variant in prehistoric times was poorly understood,” Dr Martiniano told The National.

“Our finding is very significant given that we are the first to observe this variant in ancient DNA samples, in this way directly demonstrating evidence of past malaria adaptation.”

The study marks the first investigation into the ancient genomes of Eastern Arabia, revealing the presence of the G6PD Mediterranean mutation in three of the samples.

The researchers did not discover the variant in the ancient samples they examined from Europe and the Levant.

“These insights offer some information regarding future prevention of malaria,” Dr Martiniano said.

“During the last decade, malaria was eradicated from many regions in Arabia but it still persists in others.

“Our study highlights the association between malaria proliferation and agriculture, alerting to the importance of water and environmental management for preventing malaria transmission.”

The G6PD Mediterranean mutation offers protection against malaria, suggesting that a significant portion of the ancient population in this region might have been protected from the disease.

“The mutation's rise in frequency around five to six thousand years ago aligns with the onset of agriculture in the region,” Dr Martiniano said.

“This agricultural revolution likely provided the perfect breeding ground for the proliferation of malaria.”

An analysis of Tylos-period Bahraini DNA revealed that their ancestry was closely related to ancient groups from Anatolia, the Levant and the Caucasus part of Iran.

It put them genetically closer to present-day populations in the Levant and Iraq than to modern Arabs.

This discovery adds a new dimension to our understanding of the historical population dynamics in Arabia and offers insights into the genetic predispositions of these ancient populations.

“Our findings improve our understanding of malaria adaptation as a complex process involving an interplay between genetic [G6PD mutations], cultural [agriculture] and environmental factors [such as settlements near water],” said Dr Martiniano.

“This has an impact on the choice of anti-malarial treatment, some anti-malarial drugs.”

In contemporary samples, this variant is found at a significantly high frequency among the Emirati population with substantial South Asian heritage, as well as in Pakistan and neighbouring areas.

This suggests the possibility that the variant may not be of Mediterranean origin but rather linked to South Asian or possibly Mesopotamian lineage.

Marc Haber from the University of Birmingham Dubai remarked on the significance of the findings.

“By securing the first ancient genomes from Eastern Arabia, we've opened a new chapter in our understanding of human history and disease evolution in the region,” Mr Haber said.

“This information extends beyond mere historical curiosity, equipping us with predictive insights into disease susceptibility, spread and potential treatments.”

The attempt to sequence DNA dating back to ancient Arabia faced challenges because of the region's hot and humid climate, which is not conducive to preserving it.

Nevertheless, the successful analysis of the four DNA samples, from the Bahrain National Museum's archaeological collections, represents a breakthrough in the study of the region's genetic history.

“Our study also paves the way for future research that will shed light on human population movements in Arabia and other regions with harsh climates where it is difficult to find well-preserved sources of DNA,” said Salman Almahari, director of antiquities and museums at the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities.

Diminishing immunity: Unravelling the decline in malaria protection

The mutation responsible for protecting against malaria has since weakened.

“Migration and admixture from different regions are possible causes for the introduction of variants into Arabia, and then through natural selection some mutations may be removed while others are selected,” Dr Martiniano said.

“Other mutations exist in different parts of Arabia. For example, in Oman [but also in other Arab countries], the Mediterranean mutation also occurs quite frequently, but there are other mutations too, such as G6PD A-, which is African, probably reflecting African admixture in these regions.”

In the UAE, efforts to combat malaria and its spread are exemplified by significant contributions and initiatives such as the “Reaching the Last Mile” fund, which aims to eradicate the world's deadliest diseases through a $100 million commitment over 10 years, highlighting the nation's proactive stance in the global fight against this infectious disease.

The research involved experts from Liverpool John Moores University, the University of Birmingham Dubai and the University of Cambridge, as well as various regional institutions such as the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities, the Mohammed bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dubai, and European research centres such as Universite Lumiere Lyon 2 and Trinity College Dublin.

The findings have been published in Cell Genomics.