Uncertainty surrounds the future of a world-class gold mine in Pakistan due to poor handling of the project by regional authorities.

Reko Diq is a copper and gold mine in Chagai district of Balochistan province with a value up to $500bn. It holds about 5.9 billion tonnes of ore, making it the world’s fifth largest deposit of gold and copper.

But the huge project has ground to a halt over a dispute between the provincial government and the miners.

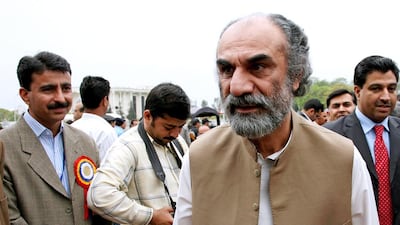

Tethyan Copper Company (TCC) – a joint venture of Barrick Gold of Canada and Antofagasta of Chile – had been awarded a licence for exploration in the Reko Diq area in 2006. In 2011, TCC’s application for a mining lease for the project was rejected by the Balochistan government of then-chief minister Aslam Raisani, which decided to run the project on its own.

TCC took the case to the international arbitration court claiming damages because it had invested more than $500 million in exploration and feasibility studies.

“There is potential … for multiple mine developments over the next few decades. By refusing a mining licence without good grounds, it’s sending quite a negative signal to the exploration/mining community,” said Tim Livesey, the chief executive of TCC, in 2012.

The rejection of a mining licence to the company after an exploration permit had been granted was an unusual decision by the government. Mr Raisani abruptly closed off communication with the company and even refused to meet its executives.

Mr Raisani rejected the TCC bid in the name of protecting the legitimate interest of Balochistan, but did his decision really help the least developed province and its people?

Balochistan has always been on the country’s political periphery, and has suffered years of neglect. The Baloch nationalist parties had reservations about the Reko Diq deal – signed with a foreign firm by the government of former president Pervez Musharaf without taking local leadership into their confidence.

Soon after the rejection of TCC’s bid, the Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC) came with a counter proposal for a mining lease for Reko Diq and offered Balochistan a larger share in income and royalty.

In 2002, MCC had acquired a lease the Saindak copper and gold project in the same district as Chagai, which expired in 2012. If the Raisani government was serious in its desire to develop deposits using local firms, why did it not oppose the five-year extension in the lease period of the Saindak project?

The Reko Diq project became controversial after news stories alleged that the Reko Diq gold mines were being secretly sold to foreign firms for peanuts.

The dispute between TCC and Balochistan began after the resignation of Mr Musharraf in 2008. Under his administration, TCC was awarded the project with mining rights and it signed a joint-venture agreement with Balochistan holding 25 per cent interest in the project. But in December 2009, Balochistan said it was cancelling the TCC deal.

That triggered a blame game, with each side accusing the other of violating mineral rules. In January 2013, former chief justice of the supreme court Iftikhar Chaudhry declared the Reko Diq contract between the Balochistan and TCC void.

Crucially, the general elections of May last year brought a new government to Balochistan, with Abdul Baloch replacing Mr Raisani as chief minister.

Mr Baloch’s government is now considering renegotiating the deal with the TCC. Both the federal and provincial governments now wish for an out-of-court settlement with the TCC. If a deal with TCC is now the best choice, why did the previous government reject the company’s bid for a mining lease?

In early 2013, Mr Raisani was removed from the post as the law and order situation in Balochistan broke down. After stepping down, he linked his removal to his decision to scrap Reko Diq deal.

In fact, the former chief minister failed to serve the interest of Balochistan when he tore up the TCC deal.

For instance, how would the cash-strapped province, which is unable to pay even the fee for legal experts, pay the damages if the international court rules in favour of TCC? In case of an out-of-court settlement, TCC would be in a stronger position to bargain over the issues related to the development of the gold mine. The Reko Diq project could lead to the development of a modern mining industry and change the destiny of the country’s least developed province.

Arbitration proceedings have further delayed the mine’s development, which has not been worked since 1993 when BHP Billiton signed a deal with Balochistan. While BHP had an exploration deal, it did no practical work and sold its 75 per cent interest to TCC in 2000. In 2006, TCC was taken over by Antofagasta and Barrick Gold.

TCC deserves credit for the discovery of the huge Reko Diq deposits. The company was willing to make an investment of $5bn over five years. It could have been the biggest foreign-financed project in the country’s history. But the short-sighted policy of the government meant this potential game changer never got off the ground.

What has been the outcome of the dispute so far? The country has missed a huge foreign investment. It has closed the door on technology transfer in mining into Pakistan and discouraged foreign firms eyeing up its mineral deposits.

Meanwhile, prospects for this world-class mine lie dormant until the final ruling of the international court.

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter