Much has been written about “the rise of the machines” and the “passive rotation” edging out active managers in recent years. While there are no signs of the debate ebbing, as the market itself has started to return to a more typical economic cycle, we have seen robust alpha generation by truly active managers. This has resulted in a renewed interest in active management.

Undeniably, the environment for active management was poor in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. For seven years through mid-2016, passive management benefited from tailwinds such as very low volatility, high correlations, slow growth, fewer stand-out performers, reduced fiscal spending, and intervention by central banks whenever any bad news emerged, all of which worked against active management.

The result has been that fundamental analysis - the backbone of active managers - was severely challenged. Meanwhile, passive investments attracted assets through dramatically lower costs, putting pressure on active management to represent true value.

According to Bloomberg Intelligence, there are now more indices than there are stocks in the US market. Despite the popularity of index investing, however, indices are in general a poor representation of the opportunity set, restrict investors' investment choices, weaken the commitment to responsible investing and carry exposure to parts of the index that are less attractive in relative terms. Passive investors buy these stocks regardless of quality, value, sustainability or return.

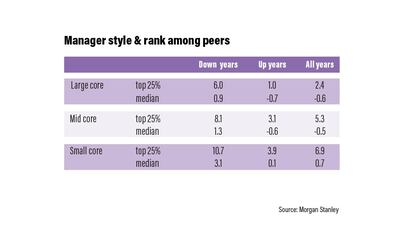

When indices are used as benchmarks, they are not subject to the same conditions and costs as the investments in a portfolio, making comparison skewed. They also can distort markets by artificially hiking prices as large numbers track the same indices. In a falling stock market, passive investors will ride the falling indices down just as they rode them up, which helps explain why top-quartile managers have significantly outperformed their benchmarks in down years.

Index providers generally focus on easily investible countries and are traditionally market-cap weighted, so larger companies dominate even if their price is high or quality low. There is a huge range of mid, small and micro-cap stocks beyond the reach of the index, though they have sufficient investable liquidity and been shown to outperform large caps over the long term.

So, what has changed?

We are now in the early stages of a major regime shift, from monetary to fiscal policy, deflation to inflation and low volatility to high volatility. Central banks are looking at normalisation, correlations are crashing and we’re starting to see “shakeout” pressure on low-alpha active managers, which reduces competition for alpha among the winners. As a result, alpha generation has been very robust in the last 12 months.

Active managers can use qualitative judgement to screen the best opportunities that may be expected to outperform over the long term—stocks that may be undervalued, particularly high quality or from less efficient parts of the market. They can offer downside protection and even capital growth during a downturn. And they can concentrate capital in big ideas. As authors Kristian Heugh and Marc Fox have written in TK: “Conviction reduces the possibility of being shaken out of undervalued ideas based on short-term noise.”

Most things in finance are cyclical. Now the tide seems to have turned in favour of active management, with stock selection again adding alpha in rising markets while dampening volatility in down markets. That said, the requirements for active managers will likely become more stringent, requiring more reliable alpha generation. Successful managers will be those that have the “active DNA” that leads to sustained performance.

This means high active share - no closet index hugging while purporting to be active - lower turnover, diversification by geography but with a focused strategy and an ability to operate in the most inefficient parts of the market.

The silver lining of the passive dominance over the past few years is that as passive has grown, there may be more alpha available. That has helped give rise to a new paradigm in the active management industry.

Paul is the global head of distribution for Morgan Stanley Investment Management