James Martin’s debts were once so bad that he took a week off work to stay in bed because he couldn’t afford to eat.

At his lowest point, he owed about £12,000 ($16,700). James found himself with about £10 a month to spend on food, sustaining himself on 6-pence packets of noodles, and unable to buy new clothes after losing about 38 kilograms of weight.

“It was easier just trying to sleep through the week until I got paid, rather than just constantly be hungry,” he says.

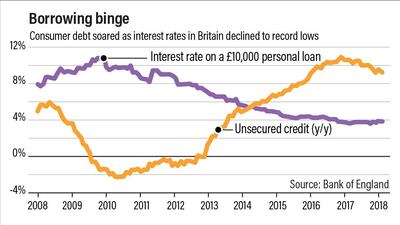

While Mr Martin was eventually able to clear his liabilities, the prospect of more Bank of England interest-rate increases this year threatens to add pressure on the more than 3 million Britons already in severe debt. At the end of January 2018, unsecured debt in the UK was about £208 billion, according to the BOE, the highest since 2008.

The BOE has warned that limited and gradual interest-rate increases are required to keep a lid on inflation. At its policy decision on Thursday, it may lay the groundwork for another move as soon as May.

A new class of employed, but struggling, debtors has been created by weak wage growth, benefit cuts and work contracts that don’t guarantee minimum hours. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, a London-based think tank, said this month that 57 per cent of people in poverty are in a household where at least one person has a job, up from 35 per cent in 1994.

As savings dwindle and budgets stretch, some households become reliant on credit to make ends meet, particularly with interest rates at a record low. That’s happened even as the unemployment rate fell to the lowest in four decades.

_________

Read more:

Britons' gloom deepens as concern over higher inflation bites

London house prices drop at the fastest pace in almost a decade

UK holiday spending squeezed by Brexit-fuelled inflation

'Brexit squeeze' on consumers to continue in 2018

__________

After more than 70 years of austerity, Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond hinted in his Spring Statement last week that he wants to soften the squeeze. The Resolution Foundation and IFS have warned that’ll be hard to achieve given the government’s budget goals.

While debt servicing costs are lower than they were a decade ago, real wages are also lower and Brexit and slower economic growth mean the outlook for pay is bleak.

In forecasts released alongside last week’s fiscal statement, the Office for Budget Responsibility said annual wage growth won’t breach 3 per cent by 2022, staying below the pre-crisis average of more than 4 per cent. In the meantime, growth in unsecured consumer borrowing is slowing, but it’s still increasing at almost 10 per cent a year.

The tipping point for debtors comes in many surprising forms, from life-changing events such as illness, to seemingly mundane mishaps like a broken boiler.

Even a single interest-rate increase could prove to be the final straw. Following the BOE’s November hike, debt charity StepChange estimated that a £20-a-month increase to the average mortgage would be enough to push about one in 10 of its clients with home loans - the equivalent of more than 10,000 borrowers - into a deficit budget.

The BOE’s Financial Policy Committee has noted the issue of high debt, but its overview of risks to the economy shows that the problem is broadly contained. While that may be true on a macroeconomic level, focusing on the big picture misses the impact on deeply indebted households.

Those borrowers are certainly a concern of Jonathan Davidson, a director of supervision at the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. At a summit in London last week, he warned that “there are a significant number of households that are in so deep that the slightest sign of rough weather could see them in over their heads.”

Charities argue that out-of-control spending isn’t the main factor.

In Mr Martin’s case, it was a housemate who lost his job and abruptly left their Manchester flat. Locked into a contract and struggling to pay rent, he relied first on his overdraft, then credit cards to cover bills. From there, it was pay-day loans and 2am calls from debt collectors. He ultimately sought help from StepChange and got a plan that allowed him to slowly clear his debt.

It’s a story that would be familiar to Lorraine Cook, who oversees 10 debt centres across the UK for the Salvation Army.

“The prospect of interest rates going up scares me,” she says. Beyond the impact on homeowners, she’s concerned about higher costs being passed on to renters and companies, who lose workers as they absorb higher costs.

About one in six UK adults are currently classed as over-indebted. StepChange alone has about 620,000 clients, while the average amount owed has edged higher to more than £13,000.

The charity is dealing with an increasing number of younger people. The typical borrower has more than five creditors, from credit-card firms through to utility companies and even local government.

There are also wider consequences. Charities report that about half of those in severe debt receive medical treatment for finance-related health issues, and many hide money problems from their families.

The issue has caught the attention of UK officials. Parliament has held hearings that focus on debt, while Andrew Bailey, the head of the FCA, last year said firms may not be doing enough to protect consumers.

Peter Tutton, head of policy at StepChange, agrees. “Struggling households will need support and protection,” he says. “We need action to ensure credit cards, overdrafts and high cost credit do not trap people in persistent debt.”