The countries of the GCC are on a path of transition and transformation to more diversified, higher-value added economies. Fiscal consolidation through expenditure rationalisation has been initiated, along with tax measures – notably the upcoming introduction of value-added tax and increases in excises, fees and charges - aimed at government revenue diversification. Energy use reforms - through higher utility charges and prices, reduced subsidies and energy efficiency measures - are expected in 2018 and beyond.

But fiscal consolidation has exacerbated the negative effects of lower oil prices by transmitting the oil shock to the non-oil sector of the economy. To counter the negative effects of fiscal austerity, GCC governments need to undertake structural reforms to remove barriers to greater private sector economic participation, public private partnerships, privatisation and digital economy activities to generate jobs. Structural reforms and incentives to support the private sector are varied, from reforms to reduce the cost of doing business, to attracting FDI and new businesses into the region, to labour market reforms and anti-discrimination measures to increase female labour participation.

Saudi Arabia’s National Transformation Program and Vision 2030 initiatives to move away from exploitation of natural resources are very ambitious (especially the recently announced US$500 billion Neom city project. The UAE’s strategy meanwhile is increasingly focused on services, high tech and the digital economy.

These strategies are critically dependent on the availability of a stock of human capital with the knowledge, skills and innovative talents suited to digital economies, adaptable to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the more fundamental upheaval that will be wrought by AI, blockchain, and associated technologies.

___________

Read more:

Corruption must not destroy the future for the Arab world

Saudi Arabia and UAE’s leap into the future

Blockchain and cryptocurrencies herald the demise of traditional banking

___________

An important part of the answer is building the human capital of UAE and GCC nationals. But this is the work of several generations and should be complemented by attracting select, foreign human capital.

The GCC is home to a large, but transient expatriate community. Residence is linked to job visas tied to a sponsor. This immigration policy impedes and leads to very low internal labor mobility, which reduces the flexibility and resilience of the economy to shocks. High-skilled labour gains experience and on-the-job training, only to migrate to more attractive prospects in other countries, with the host countries of the region bearing the cost of labour turnover with a new set of expatriates.

This is a deadweight loss to both parties. With little incentive offered to retain high-skilled, high-productivity labour, the countries of the region are losing out as other countries compete to attract them.

The UAE announced earlier this year that committees would be set up to identify “the vital sectors that will be open for specialized visas, and to draw a plan to attract the most notable, exceptional regional and international talents”. This is indeed a step in the right direction. But much more needs to be done to attract high-skilled, high-productivity labour; they need to be provided with well-designed incentives to stay long-term.

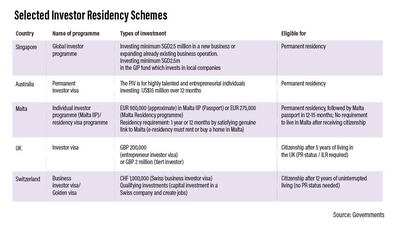

An effective policy tool for the GCC countries and the UAE is to develop and institute a long-term investor residence programme, to attract investors, human capital and technology. Many countries currently run successful long-term investor residency programmes, ranging from Singapore’s “Global Investor Programme” to Estonia’s innovative E-residency programme (where the e-resident is a non-resident person with an Estonian digital identification, who is able to use Estonian online services, open bank accounts, and start companies without ever having to physically visit Estonia).

A quick overview of select, existing residency/ citizenship programmes is given in the table below:

There are multiple benefits to a long-term investor residence program. The UAE would attract and retain qualified human capital and increase the inflow of FDI and transfer of technology. It is estimated that residence-by-investment programmes attract at least $5bn a year in fresh FDI, and citizenship by investment another $2bn annually. In addition, long-term residents would retain their saving and increase their investment in the UAE and reduce remittances.

The impact on the balance of payments of reducing remittances would be substantial. For example, UAE expatriates sent $43.81bn in outward remittances in 2016, compared to $45.56bn in oil exports. Government could issue bonds or sukuk for infrastructure or development projects for permanent residency investment, helping develop a long-term government debt market.

The UAE would specify which sectors or activities could qualify for the investor residency program. Qualifying investments could be high tech, knowledge sectors such as AI, life sciences, fintech or other priority sectors identified for diversification. Given the current large real estate overhang, introducing a permanent residency linked to property and real estate investment, including holiday and retirement homes, could attract large inflows.

Retirees would be both investors and consumers, including on health and related services while attracting family members to visit, increasing the flow of tourists. The bottom line is that a permanent residence program can be a major contributor to the success of diversification and transformation strategies.

Nasser Saidi, the former chief economist of the Dubai International Financial Center, is a former vice governor of the Bank of Lebanon and has served as Lebanon’s minister of the economy and industry.

He is the author of the OECD report on Corporate Governance in the Mena Countries.