The US Fed will be normalising monetary policy in 2018, reversing the loose, unconventional policies it has pursued since the onset of the financial crisis 10 years ago. This means rising interest rates and monetary tightening.

The UAE and other GCC countries (with the exception of Kuwait), whose currencies are pegged to the US dollar, will therefore have to follow suit and raise domestic interest rates, their monetary policy driven by the Fed's actions rather than their own needs. Higher interest rates mean the cost of borrowing (on debt, loans, credit facilities and so on) for government, businesses, households and consumers will become more expensive.

Tighter monetary conditions will also result in lower spending and investment. This will dampen economic activity and growth prospects in the UAE, and elsewhere around the region, exacerbating the negative effects of fiscal austerity, recently imposed taxes (VAT and excise duties), geopolitical risks and uncertainty.

US monetary policy, which is geared to the needs of the US business cycle, is not suitable for the economies of the UAE and GCC, which are facing a period of lower growth. The current mix of monetary tightening and fiscal austerity is pro-cyclical, and directly conflicts with the need for GCC countries to conduct a counter-cyclical policy, including monetary loosening and lower interest rates, together with structural reforms in order to adjust to the "new oil normal" of lower prices.

The peg to the US dollar in the past provided an anchor for local currencies, imposed monetary discipline and led to moderate inflation rates. However, it is no longer appropriate for maintaining macroeconomic stability and addressing the GCC's economic development and diversification objectives to transition away from oil-based economies.

A new exchange rate regime

Economic analysis and country experience suggests that exchange rate flexibility is appropriate to address real domestic or external shocks (for example, terms of trade fluctuations) or foreign nominal shocks (foreign inflation shocks), whereas fixed exchange rates are more effective in achieving macroeconomic and financial stability in reaction to domestic nominal shocks.

The strict dollar peg is counter-productive and is no longer the appropriate exchange rate regime for the UAE and other countries in the region for two major reasons. Firstly, a flexible exchange rate regime is required for adjustment to address the real economic shock of the new oil normal, which imply a deterioration in the terms of trade and lower real incomes. Secondly, the peg does not reflect the deep structural changes in the GCC's economic, trade and investment patterns and financial links since the 1980s and the growing shift to the east, to Asia and China (see table).

Greater exchange rate flexibility across the GCC is required to maintain international competitiveness of the region's expanding non-oil sector, whether it is tourism, or industry. GCC states need a more independent exchange rate regime linked to dealing with the business cycle conditions of their main trade and investment partners, which are now the Asian countries and no longer the US and Europe. Other oil exporting countries, such as Russia, have allowed their exchange rates to depreciate, easing adjustment to lower oil prices by contrast to the GCC countries which maintained fixed rates.

Moving to a currency basket

Many options are available in moving from a tight US dollar peg to greater exchange rate flexibility. Pegging to a currency basket allows for some monetary policy independence and exchange rates that respond to macroeconomic shocks. Adopting a currency basket with a band (movements of 5 per cent on either side of a central rate) would provide exchange rate flexibility and enable central banks to deduce a monetary policy that is aimed at regional macroeconomic and financial stability.

Macroeconomic volatility can result from trade shocks and technological disruptions, as well as inflation, oil and non-oil output (business cycle) shocks. For internationally financially integrated economies, financial shocks can also lead to macro volatility. An optimally designed currency basket should take account of the trade, inflation, output and financial linkages between the GCC and its major partners.

_______________

Read more:

Why the GCC should adopt the petroyuan

Why the UAE should institute an investor residency programme

Corruption must not destroy the future for the Arab world

_______________

Based on this analysis, the GCC (individual or common) currency baskets should include the dollar, the euro, and Asian currencies such as yuan, given China's status as the region's top trade partner. The individual currency weights in the basket can be adjusted over time to reflect structural changes in trade, output, inflation and financial linkages.

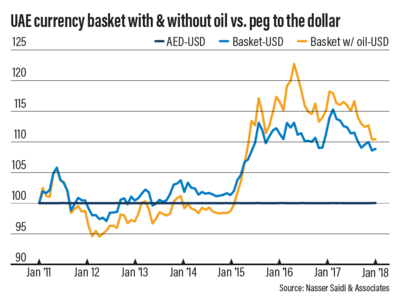

Given the region's dependence on oil exports, an oil-price augmented currency basket would also be an option. For example, including oil prices with a weight of 10 to 15 per cent in the basket would automatically allow adjustment in terms of trade shocks and real shocks, and imply a depreciation (or appreciation) of GCC currencies given a decline (or rise) in oil prices.

The chart above shows a simulation for a UAE currency basket without and with (more fluctuations) the oil price. The UAE dirham would have depreciated since 2014, smoothing adjustment to the oil price shock, and favouring the growing non-oil sector, notably tourism and services industries.

There are some important caveats for introducing a currency basket-based exchange rate mechanism. Policy sequencing is particularly important. Exchange rate regime change should be preceded by fiscal reforms (revenue diversification, targeted subsidies) for fiscal sustainability, and to anchor exchange rate expectations. Similarly, monetary policy independence requires policy tools for market intervention to accompany greater exchange rate flexibility. The GCC region needs to develop broad, deep and liquid local currency money markets and government debt markets to provide instruments for the conduct of monetary policy and exchange rate market interventions.

As the UAE and GCC economies mature, they require an arsenal of economic policy tools to diversify their economies, for macroeconomic stabilisation, economic diversification and fiscal development. Currency basket-based exchange rate mechanisms would certainly be a step in the right direction.

Nasser Saidi is the former chief economist of DIFC and has served as Lebanon’s minister of economy