The scooter rental company Bird Rides has quietly begun abandoning its practice of paying independent contractors a per-vehicle rate to fix its scooters in several cities.

In late February, mechanics working in San Diego received an email saying their services would no longer be needed, and that they should repair any vehicles in their possession and return them to the company immediately. Last week, mechanics in Phoenix and the Los Angeles area said the feature in Bird’s app they used to find work had been unceremoniously disabled. “In order to better serve the community, we are expanding our in-house repair facilities,” the company explained in its email to mechanics in San Diego.

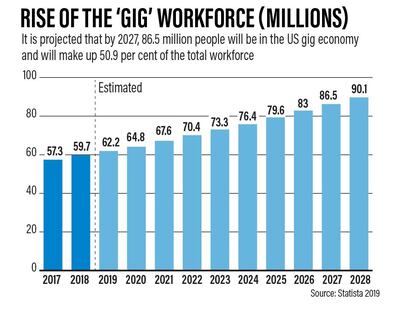

Over the past several years, many start-ups have pursued a controversial alternative to using employees to provide the services they’re selling. Instead, they establish short-term, smartphone-based labour marketplaces where workers compete to, say, drive someone across town, or deliver a burrito. Scooter companies have become one of the big new venues for such work, sometimes called the gig economy. As they spread electric scooters out across dozens of cities, companies like Bird and Lime began paying people a piecemeal rate to recharge them and, in Bird’s case, repair them.

The company’s recent move illustrates the difficulties of such a decentralised operation, and the suddenness of the pivot also hits home the uncertain economic prospects for people relying on gig economy platforms for income.

Bird confirmed that it’s abandoning the idea of dispatching independent mechanics through a smartphone app. “We have found the independent contractor side doesn’t work as much there,” said Travis VanderZanden, the company’s chief executive. “What we’ve decided to do is move it all to service centres.” The company didn’t say it would hire its own employees at these service centres; it uses staffing agencies for some hourly repair work already. Bird will continue to pay people a per-vehicle rate to charge scooters.

The new model will give Bird tighter control over its repair operations. It exerted very little influence over its gig economy mechanics. After applying online, doing a phone interview, watching training videos online, and getting a small set of tools in the mail, they’d get access to a feature on Bird’s app to find broken scooters. They’d fix those that could be repaired, and take the rest to Bird facilities, where Bird hired hourly employees to make more significant repairs. As with other gig economy jobs, pay varied according to the number of scooters needing repair and the number of mechanics available to fix them. Mechanics said they’d average $15 per repaired scooter, and could bring in as much as $400 on a good day.

Four mechanics who went through the vetting process said it left them feeling uneasy. “It wasn’t like a regular job. It was like, ‘You have the skills? We’ll take your word for it.' It was kind of sketchy,’” said Ozzy Lagunas, a 25-year old San Diego resident who used his earnings to supplement the wages he earned helping prepare health exams for people applying for life insurance. On a busy day, he said, he’d make $300.

Mr Lagunas felt like he was on his own. He said Bird didn’t supply sufficient spare parts, so he’d harvest badly damaged scooters to get more lightly worn vehicles back on the road quickly. The next rider would often hop on before anyone else had checked his work. Once, Mr Lagunas said he fell while testing a scooter he was repairing. He hit his head and scraped his knee, and considered going to the hospital. He called the company to see what help it could provide, but it didn’t offer any. He said he decided to make due without medical care. Bird didn’t respond to questions about Mr Lagunas’ account.

The scooter craze has inspired questions about safety. Many people have suffered serious injuries riding scooters, and several lawsuits charge that the negligence of Bird and its competitors is to blame. “These companies are putting profit over safety,” Catherine Lerer, a lawyer representing one group of plaintiffs, said in October. At the time, Bird issued a written statement saying class action attorneys would do better to focus on safety issues related to cars.

Mr Lagunas said he saw Bird’s decision to bring repairs in-house as a prudent safety move. There’s evidence that not all of the company’s maintenance issues can be attributed to the gig model, though. A lawsuit filed in January by a mechanic who worked an hourly job through a contracting agency alleges that Bird instructed workers to ignore safety problems. Court filings show internal messages telling workers that scooters with loose handlebars and missing screws shouldn’t be considered damaged. The case is pending. Bird has yet to respond.

There is also increasing uncertainty about whether the gig economy is legal. Last spring, the California Supreme Court made it harder for companies to classify workers as independent contractors. Since then, at least four people who worked for Bird as chargers or mechanics have filed separate lawsuits, alleging the company has mis-classified them as contractors. They claim the company has used this practice to avoid paying minimum wage and granting its workers other benefits of full-time employment. In court filings, Bird has denied charges that it mis-classified workers.

“While we are not able to comment on the specifics of former contractors or ongoing litigation, we can share that as a transportation company the safety of our riders, chargers, mechanics and all others who interact with our vehicles is our utmost concern,” said a Bird spokeswoman.

The way Bird handled the change left some mechanics feeling blindsided. By last October, a San Diego-based mechanic named Alex Frost said he was making enough money to quit his job in sales at an auto body detailing shop. He made at least $130 most days, and on busy days would work over 10 hours and make as much as $400. Mr Frost said Bird gave him no notice, and didn't offer him a chance at a conventional job. “I’ve invested my time into the business, to learn what they want, and to do what they need to have done,” he said. "So why wouldn’t they just retain us as employees?"

Another mechanic working in Riverside, California, said his experience with Bird had followed a pattern he recognised from other gig economy jobs. They’re all lucrative and flexible at first, but the earnings erode over time as competition increases and the platforms look to squeeze out better margins. The man, who asked to be identified by only his first name, Mike, said the same thing had happened when he ferried riders around for Uber and other similar firms.

Mike described the routine he developed over five months working for Bird. Each evening after putting his kids to bed, he would drive around town, picking up damaged scooters and piling them up in his garage. He’d wake up and take the children to school in the morning when his wife went to work, then spend a few hours fixing flat tires and broken brakes until it was time to pick them up.

As time went on, it became harder to find enough scooters to justify the time. Also, an increasing proportion of the vehicles he did find would be too damaged to repair; he’d drive those to a storage facility about 20 minutes from his home. This made financial sense so long as he could get a full load.

One Monday, Mike dropped off a batch of scooters at the storage facility. When he opened the Bird app to find some more, the section for mechanics had just disappeared. He wasn’t surprised.

“It always sucks to lose money, no matter who you are, no matter how much you make,” said Mike. But he also knew he couldn’t count on any form of income security.

“Doing the gig economy,” he said, "you learn that.”