Myanmar risks losing billions of dollars of foreign direct investment and diminished growth prospects after the South East Asian slipped back into military rule this week.

The country, which is already reeling from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic that halted several projects, risks an exodus of international investors.

"We're going to get a situation where there's going to be a knee-jerk natural reaction where investors just stop. They don't need to be encouraged," said Stephen Innes, chief global market strategist at Axi.

"Any further investment is just going to halt and there will be outflows, people will be rushing to get their money out," said Mr Innes, who is based in neighbouring Thailand.

Capital flight will deal a significant blow to Myanmar's economy, which has been heavily reliant on foreign direct investment to revitalise certain critical sectors. Trading on the four-year old Yangon Stock Exchange, which has six listed companies, was suspended after the benchmark fell 6 per cent following the coup.

The power and infrastructure sectors have been the biggest beneficiaries of foreign investment following the end of the military junta rule in 2011. The sector drew more than $21.8 billion, accounting for a fifth of overall FDI in the financial year 2019-20, according to Fitch Analytics.

Myanmar, which also has significant gas reserves estimated at 23 trillion cubic feet risks $2bn worth of projects reaching final investment decision, according to consultancy WoodMackenzie.

Companies with longer-term infrastructure or exploration deals must be "nervous", said Tim Dobermann, an economist covering Myanmar.

"Renegotiating existing gas export contracts is likely to prove contentious and may not be a fight the military government wants to take up at this point in time," he added.

The country, formerly known as Burma, is likely to see a backlash from investors as international sanctions are likely to be applied against the military regime.

G7 foreign ministers of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US and the High Representative of the European Union, condemned the coup in Myanmar.

They called upon the military to immediately end the state of emergency, restore power to the democratically-elected government, to release all those unjustly detained including Aung San Suu Kyi and to respect human rights and the rule of law.

The 10-member Asean bloc, which comprises South East Asian nations that Myanmar belongs to, called for peaceful dialogue.

Most of the big investors in Myanmar come from the surrounding region as the country straddles both South and South East Asia.

China, for instance is the biggest foreign investor in the power and infrastructure sector, accounting for 29 per cent of all investments.

Other key foreign investors in the infrastructure space are India with a 14 per cent share, followed by Japan with an 11 per cent interest.

Following the end of the junta rule, Myanmar had become an exporter of gas to Thailand and China.

There may be pressure on the country's exports, Mr Innes said.

However, gas projects that are Chinese-led are unlikely to face cancellations as Beijing has previously co-operated with the military and Ms Suu Kyi, according to WoodMackenzie.

Myanmar's Asean neighbours are also likely to be cautious, factoring in the economic impact on the country and the region as a whole before taking a political stand, said Mr Innes.

"For Asean [countries], it becomes more of an economical impact because trade barriers are more closely linked in this area," Mr Innes said.

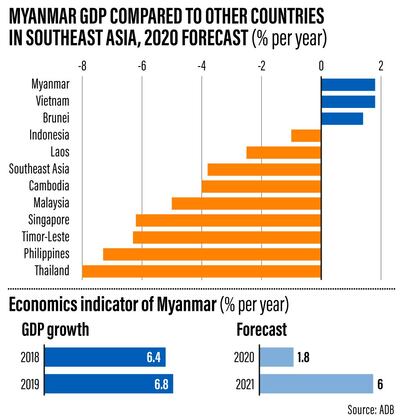

South East Asia's economy as a whole is set to have contracted by 4.4 per cent in 2020, according to the Asian Development Bank. The region is set to rebound to growth of 2.2 per cent in 2021, which is significantly lower than forecasts for South and Central Asia, which are expected to see 4.5 per cent and 6.5 per cent growth rates, respectively.

Myanmar, touted as Asia's last frontier economy managed to avoid a contraction last year, expanding 1.8 per cent. Prior to the coup, the ADB projected the economy would grow 6 per cent in 2021.

The political turmoil is likely to have a significant impact on the country's power and infrastructure sectors, which have already been weakened by the pandemic, making access to finance challenging.

The political unrest in the country has already led to the suspension of work across construction sites in Yangon, Myanmar's largest city and the former capital.

Fitch Solutions also warned of higher Covid-19 infections in the country following mass protests against the government. The analytics firm revised its forecasts for the power and infrastructure sectors over the near and medium term on the basis of significant headwinds.

Project developers and financiers are likely to withhold final investment decisions on projects due to the "elevated risks in the market", the report added.