As they look to ease monetary policy, central bankers are also singing from the same songsheet when it comes to government support for their economies. They want more of it.

With the global growth outlook darkened by trade wars and borrowing costs already low, central banks say they can't dispel the clouds on their own. From Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell to European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, the demands are mounting for governments to loosen their budgets if the slowdown takes hold.

Markets are flashing a green light. It's rarely been cheaper for governments to borrow - in many cases, investors end up paying them, since yields are negative. All kinds of economists, including the ones at the International Monetary Fund, agree that fiscal support is probably the way forward.

The questions are: which finance ministries have room to help and which are listening?

It's harder to track fiscal stimulus than the monetary kind. There are more instruments, with taxes and spending split across national or local levels that are hard to condense into a single number. (And different calculations can produce different results - here, IMF numbers are used throughout). The greater complexity is one reason why fiscal policy, while critical to understanding the economic outlook, gets less attention than central banks.

Following is an overview of the fiscal state of play in the world's most important economies - what governments are doing and what they're talking about doing.

US: loose - but gridlocked?

* 2018 Budget Balance: -4.3 per cent of GDP (deficit)

* 2019 Forecast: -4.6 per cent

The US has been loosening fiscal policy under President Donald Trump. His combination of tax cuts and higher spending is unorthodox in an economy that’s been expanding for a decade. It did deliver a bump in growth last year, which is now fading. It also left the US looking a bit like Japan a few years earlier - with a deficit above 4 per cent of GDP and forecast to stay there for a decade.

Markets seem to be fine with the Trump stimulus. The president's problem is that he has no easy way to repeat the trick. His Republican Party lost control of Congress and therefore the purse strings as of this year. America has a debt ceiling that has to be increased before spending can rise and there's usually a political row. The latest one just got resolved, in a deal that suspends the ceiling for two years and edges spending higher. But there's little incentive for Democrats, who want to beat Mr Trump in next year's presidential election, to juice the economy in ways that might help him.

What the economists say

Fiscal hawks are a rare breed in Washington at the moment, and economic momentum is in any case not sufficiently robust to endure any meaningful austerity - after all, the Fed has deemed the economy frail enough to warrant renewed policy accommodation. The chance of additional stimulus being incorporated ahead of the 2020 election is remote, given the nearly insurmountable hurdle of crafting a package that would appeal to both House Democrats and Senate Republicans.

Carl Riccadonna, Bloomberg Economics

Euro zone: Germany says 'nein'

* 2018 Balance: -0.6 per cent (deficit)

* 2019 Forecast: -1 per cent

Budget politics in the euro zone make the American debate look friendly. Europe is hobbled before it comes to the fiscal starting line because there’s no authority parallel to the European Central Bank that can tax and spend on the continent’s behalf - while individual members lack the flexibility that comes with printing your own currency. Plus, the most powerful country, Germany, is obsessed with balanced budgets.

What the economists Say

For the first time in many years, the euro area is loosening fiscal policy but not by much. Some countries, such as Germany, have considerable fiscal space and, when the next recession hits, the debate on government spending is likely to heat up considerably.

The new ECB president, Christine Lagarde, will try to convince policymakers that monetary policy can't be the only show in town. However, politics may end up preventing any significant loosening of the purse strings.

David Powell, Bloomberg Economics

It's at the national level that budgets get decided, though the EU's central authorities can intervene to cap deficits. Out of the three biggest Euro economies, one is injecting stimulus; one wouldn't dream of it; and one is desperate to do so but has been told it's not allowed.

France: Yellow-Vest boost

2018 Balance: -2.6 per cent (deficit)

2019 Forecast: -3.3 per cent

President Emmanuel Macron's tax cuts in response to the Yellow Vest protests are lifting the economy just as the euro zone slumps. They'll amount to a stimulus of around Dh69.92bn, or 0.5 per cent of GDP. That's on top of a one-off boost for businesses this year from changes in tax credits.

France isn't the obvious candidate for belt-loosening in the euro zone. With debt already near 100 per centy of GDP, the national auditor has warned that Mr Macron's largesse has derailed efforts to repair the public finances from the last global crisis, and won't leave much room if there's another one.

France plans to resume tightening next year, with spending cuts and the removal of corporate tax-breaks, to get the deficit down to 2.1 per cent of GDP. It’s hoping Germany will pick up the baton of fiscal stimulus, and has proposed a deal along those lines known as the “growth contract.” So far, Berlin hasn’t responded.

Germany: balancing act

2018 Balance: +1.7 per cent (surplus)

2019 Forecast: +1.1 per cent

The German government's own numbers show the budget in perfect balance for a sixth straight year – as it's constitutionally required to be, outside of recessions. (The IMF calculates that it's actually in surplus.)

Zero deficits have been a hallmark of Chancellor Angela Merkel's government and not one that's likely to be abandoned easily, even as economic sentiment at home worsens and external pressure grows. When analysts calculate which countries have "fiscal space,'' Germany is usually top of the list – and it's likely the main target of ECB chief Mario Draghi's increasingly

loud demands for some spending support.

But the government brushes off such calls. The public argument is that current economic problems aren't too severe yet, and are global in nature anyway. Behind the scenes, finance ministry officials are wary that a deep slowdown could be on the way - and their mantra is that Germany needs to keep its fiscal powder dry so it can pull itself and maybe all of Europe out

of a recession.

Italy: battling Brussels

2018 Balance: -2.1 per cent (deficit)

2019 Forecast: -2.7 per cent

Italy, with a long-stagnant economy, wants to kickstart growth by widening its deficit, but it's run up against EU rules. Twice in six months, it's had to compromise over budget

targets to avoid giant fines.

The populist government in Rome may yet have some cards to play, though. It's seeking to avoid implementing an already legislated sales-tax increase next year, while speeding up cuts in income and corporate tax rates - and leaving income-support and early-retirement programs intact.

To avoid another blowup with Brussels, the government may have to consider taking away a host of tax breaks enjoyed by various groups, which won't make voters happy. And it has a couple of other avenues for raising revenue – like squeezing more dividend payments out of state-owned companies, and extending a crackdown on evasion that has already netted settlements from UBS and the Gucci fashion empire.

Japan: taxing time

* 2018 Balance: -3.2 per cent (deficit)

* 2019 Forecast: -2.8 per cent

Japan has a big budget landmark coming up: a proposed increase in the sales tax in October. It's been in the pipeline for a long time, and the government says it's essential to trim the world's biggest national debt.

But as the date nears, some policy makers are getting edgy.

They're arguing that Japan has got burned this way before - by withdrawing fiscal stimulus too soon, with tax increases that tipped the economy back into recession. Some policymakers want a spending boost alongside the tax, to make sure that doesn't happen again.

Japan has been tightening policy after running some of the world's biggest budget deficits in the five years after the financial crisis - averaging almost 9 per cent of GDP. It's often cited

by Modern Monetary Theory, an economic school which backs active use of fiscal policy, to show that deficit-spending needn't trigger inflation or scare bond vigilantes. Now Japan is having a lively domestic debate about MMT, whose advocates say the sales-tax increase is a mistake.

What the economists say:

Victory for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's ruling coalition in the upper-house election will reinforce Abe's plan to go ahead with a sales-tax hike in October. The hike could add about ¥5

trillion(Dh173.71 billion) in revenue, according to government estimates.

But much of that will go on funding free education and providing subsidies for the low-income elderly, not to reining in the budget deficit. This will be a short-term positive for growth, but a negative for Japan's debt trajectory in the longer term.

Yuki Masujima, Bloomberg Economics

UK: austerity over?

* 2018 Balance: -1.4 per cent (deficit)

* 2019 Forecast: -1.3 per cent

Britain has spent the years since the financial crisis bringing down the biggest budget deficit in peacetime history. It stood at 10 per cent of GDP when the Conservatives took office in

2010; last year it fell to little more than 1 per cent, the lowest for 17 years.

New Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his chancellor, Sajid Javid, appear intent on throwing off the shackles with promises of income-tax cuts and money for health, education and policing.

It's part of what the government calls economic "boosterism" as it prepares for Brexit on October 31 and even a possible general election. Mr Johnson's tax cuts could lift GDP by 0.3 per cent but the benefits would be dwarfed by a no-deal Brexit, according to Bloomberg Economics.

What the economists say

After nearly a decade of austerity, the tide appears to be turning for UK fiscal policy. Boris Johnson, the new prime minister, has touted £20bn (Dh88.32bn) of tax cuts (about 1 per cent of

GDP) and has made a series of spending pledges. Delivering on those promises will be made all the more difficult if the UK crashes out of the EU without a deal. We think that could blow a £30bn hole in the public finances.

Dan Hanson, Bloomberg Economics

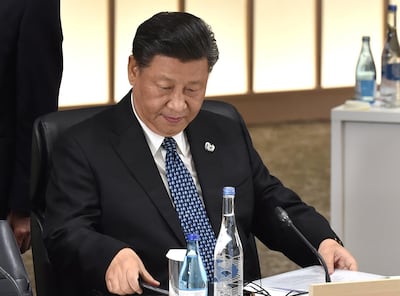

China: quietly loosening

* 2018 Balance: 4.2 per cent (deficit)

* 2019 Forecast: 4.5 per cent

China has stepped up its use of fiscal firepower this year, rolling out tax cuts estimated to be worth 2tn yuan (Dh1.02tn). At about 4.5 per cent of GDP, the official deficit covers only part of the government-led expenditure planned for 2019. When off-balance-sheet spending is taken into consideration, the actual deficit forecast widens to at least 6.2 per cent of GDP.

The whole system in China is different, though. The central bank has few claims to independence and the government officials who control policy can boost the economy by pumping loans into chosen sectors, as well as direct spending. (They also might face pressure to rein that credit in). So the fiscal numbers only capture part of what the government's doing to

stimulate or cool the economy.

The splurge has increased debt but it's also alleviated some pressure on China's central bank, enabling the People's Bank of China to refrain from broad-based easing for now. How well this year's massive fiscal stimulus can feed into the economy is unclear. Infrastructure investment growth is still hovering at a low level, and a considerable part of government- bond proceeds have been used for reserves, not in projects that can generate steady cash flow or drive production along the supply chain.

What the economists Say

Facing the escalation of the trade war and the slowing in the growth, the government has pledged to run a proactive fiscal stance. So far this year, it has cut taxes and increased the quota for local government bond issuance. There is still room to use fiscal policy to stabilise growth. Although we do not expect the government to widen the general budget deficit, the special government bond issuance quote could be increased to provide stronger support for infrastructure spending. Regulatory relaxations such as controls on public-private partnerships could also provide a meaningful boost to demand.

David Qu, Bloomberg Economics