There was a surge of optimism in South Africa in February, when Cyril Ramaphosa was elected as president to replace Jacob Zuma, whose name by then was synonymous with corruption and who is now standing trial in the South African High Court.

Promising to reverse a decade of economic decline and inequality, President Ramaphosa vowed to introduce business-friendly reforms to stimulate investment and halt unemployment, which stands at around 27 per cent. He also pledged to stamp out corruption and strengthen inefficient state systems.

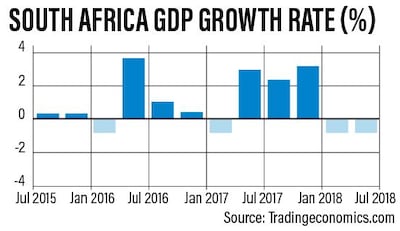

Yet within months, South Africa’s future had clouded over again. The country’s economy entered a recession in the second quarter of this year for the first time since 2009, prompting the International Monetary Fund to lower its growth forecasts, citing political and economic uncertainty.

After contracting 0.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter by the end of July, the economy is now expected to expand by 0.8 per cent in 2018, down from a forecast of 1.5 per cent in July. It is expected to grow 1.4 per cent in 2019, down from a previous estimate of 1.7 per cent, the Washington-based lender said in October.

The rand has plummeted nearly 20 per cent this year, sovereign debt is junk-rated and international investors remain skittish following corruption scandals such as that of the Guptas, a family of Indian-born businessmen accused of influencing the awarding of state tenders during Mr Zuma’s reign. A public investigation is underway and the Guptas deny wrongdoing.

Meanwhile, President Ramaphosa’s attempts to attract foreign direct investment are being undermined by controversy around his land reform initiative, a populist programme to redistribute land to the country’s black majority.

While he told Bloomberg in September there would be “no mayhem and no land grabs”, investors are fearful of the potential for unrest, which could cause the economy to slide further. Credit Suisse, Switzerland’s second-largest bank, last week pulled out of South Africa after 13 years. Deutsche Bank has scaled back operations in the country.

“The euphoria around President Ramaphosa’s election this year has subsided because he initially focused on policies less conducive to growth, such as the land reform programme, while only launching structural reforms by the end of the third quarter,” Dubai-based Arqaam Capital said last week.

Such reforms include the 50 billion rand ($3.5bn) stimulus package announced by the government in September, comprising “reprioritised expenditure and new project-level funding” to boost economic growth, and a 400bn rand medium-term infrastructure fund. Mr Ramaphosa aims to attract funding from development institutions, banks and other investors.

Despite the stimulus, Arqaam projects South Africa’s debt to GDP ratio to rise to 55.7 per cent by the end of 2018 from 53 per cent last year, and said cutbacks equating to around 1 per cent of GDP are needed to stabilise the situation.

Amid the turmoil, policymakers hope to seed green shoots of recovery.

“The South African economy has had a decade of very slow growth,” said Paul Currie, chief investment officer of the Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA), a development finance institution wholly owned by the South African government with 30bn rand of capital and an 80bn rand loan book.

_______________

Read more:

Africa courts investors with reforms, but challenges remain

Exclusive: EFG Hermes steps up coverage of frontier markets in Africa and Asia

South African rand rallies ahead of Ramaphosa address

_______________

“We’ve had significant political wobbles over this period and there’s been evidence of governance challenges across the public and private sectors. As a result, we haven’t seen much growth above 2 per cent for 10 years.”

Optimism at the election of President Ramaphosa "has subsided and nothing much has happened in the year since he came in”, Mr Currie added.

While South Africa has a robust formal economy – its banks are well capitalised with adequate liquidity, its stock exchange is the largest on the continent and South Africa accounts for 80 per cent of total African pension fund assets – there is a growing informal economy comprising the livelihoods of its most vulnerable populations, which is not being serviced by current job creation efforts, he said.

“There is a unique opportunity for courageous decisions to stimulate growth and allow the economy to kick start – if you can create the confident and transparent environment for that investment to take place.”

DBSA is working with banks and other institutions to develop new funding platforms that draw in private sector capital to finance initiatives "for the common good", Mr Currie told The National, during the Africa Legal Network forum in Dubai last week. Those vehicles will invest in underlying infrastructure projects, from housing to logistics and, ideally, sit within an umbrella programme to give confidence to investors.

The first such fund DBSA is coordinating aims to finance the construction of 3,000 beds of student accommodation in South Africa. Mr Currie hopes similar funds will gain traction over 2019.

He noted that previous programmes such as the South African Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Programme has mobilised around 200bn rand from the private sector since 2010 to build renewables infrastructure in the country. “If the environment is predictable, simple and transparent enough, it can work.”

The Gupta affair, he said, “was an unfortunate manifestation of a culture that was starting to develop [under Mr Zuma]. What is necessary is to move away from that and show that those processes have stopped and there will be no reward for people who involve themselves in that type of thing.” The establishment of public-private investment funds is one way of doing this.

Mr Zuma caused “a lot of reputational damage that does not represent the reality on the ground”, added Barnaby Fletcher, senior analyst for Southern Africa at consultancy Control Risks.

He said the land reform issue could be less controversial than feared, but any threat to the agricultural industry – one of the biggest contributors to South Africa’s GDP – could have a knock-on impact on investment.

The land debate has also clouded people’s perceptions of President Ramaphosa’s more business-friendly policies, he added. Among the sectors South Africa wants, and is well placed, to open up to private sector investors are manufacturing, technology, and power and utilities.

“Government rhetoric must focus on reclaiming South Africa’s status as the gateway for the rest of southern Africa,” Mr Fletcher said. While Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and others are jostling for a piece of the foreign investment pie, South Africa remains the financial and judicial capital.

“Recent reforms in South Africa, such as measures to tackle corruption, strengthen procurement and eliminate wasteful expenditure, are welcome,” the IMF said in October. “However, further reforms are needed to increase policy certainty, improve the efficiency of state enterprises, enhance flexibility in the labour market, improve basic education, and align training with business needs.”

South Africa's opposition leader Mmusi Maimane told The National he concurs with the above and believes the country should go further – by privatising or part-privatising its ineffectual state bodies, including airlines, energy and utilities companies.

“South Africa needs change, and part of that is to move from a state-led to a market-based economy,” he said. He also called for more robust efforts to attract investment.

“South Africa has gone through a missed decade and desperately needs reform.”

South Africans, and prospective investors circling one of the continent’s most sophisticated countries, will be hoping for a smoother ride in 2019.