Follow the latest updates on Afghanistan here

Political turmoil in Afghanistan risks reversing economic gains made in the already fragile country, which depends on foreign aid and international support.

The Taliban have seized control, 20 years after they were ousted in a US-led invasion.

“We have every reason to be extremely pessimistic about Afghanistan’s economy. I don’t see economic stability in the country for many years to come. For that, one must have law and order,” said Talmiz Ahmad, a former Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE.

Afghanistan’s economy has been primarily dependent on foreign aid with domestic revenue sufficient to finance only around half of budgeted expenditures, according to the World Bank.

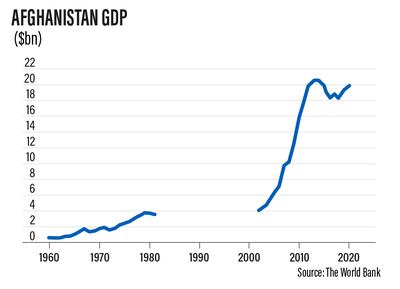

The country's economy grew an average 9.4 per cent between 2003 and 2012, driven by a booming aid-supported services sector and farming output.

Economic activity slowed to about 2.5 per cent per annum between 2015 and 2020, according to the Washington-based lender.

As a result of Covid-19, the onset of a drought, lower remittances, declining trade and growing instability in the country, the International Monetary Fund revised its growth forecast in June downwards to 2.7 per cent this year from an earlier 4 per cent estimate.

Inflation in the country had increased and was forecast to reach 5.8 per cent by the end of this year. With the collapse of the government, food prices are set to rise as borders with neighbouring countries close and panic buying sets in leading to a further surge in inflation.

“Our business got drastically affected in the last one month and we had to shut down our operations temporarily,” said Abdul Momin, chief executive of Momin Group, a Dubai-based company that produces and markets edible oil in addition to distributing electronic products and sugar.

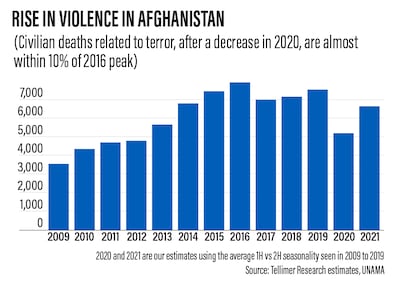

Political turmoil and security concerns are likely to dent economic activity further as foreign embassies, non-profit organisations active in the country and other entities involved in reconstruction relocate their staff.

“Legal and illicit capital flows out of Afghanistan [are] likely [to] accelerate amid the ongoing upheaval,” Hasnain Malik, emerging and frontier markets strategy analyst at Tellimer Research in Dubai, said.

“Non-government foreign investment into Afghanistan likely remains minimal until such time as a new government is in place and if it is dominated by the Taliban then the main sources of that investment are likely to be China and Russia.”

The fluidity of the situation could also lead to an exodus of workers, according to Nihar Ranjan Das, a specialist on South Asia and a former Indian Council of World Affairs official.

A complete takeover of the country by the Taliban could lead to half the country's workforce being driven out “especially because they will probably not allow women to work,” Mr Ranjan Das said.

“Foreign direct investment is now going to be very difficult to come by. No company will want to invest in a country with no assurance of any returns.”

“UAE companies with operations in Afghanistan may not suffer that much,” Mr Das said. "The Taliban may be slightly supportive of the investments made in Afghanistan by the UAE.”

Dubai could benefit “in terms of both bank deposits and real estate, [we] should see some inflows from Afghanistan”, said Mr Malik of Tellimer. “But this has likely been going on for some time and the change is not material,” he said.

China, Russia and Pakistan are likely to have a wider role to play due to their investment and security ties with the country.

Before the Taliban seized power, as a sign of support for Afghanistan’s development and reforms, international donors had pledged $12 billion in civilian grants over 2021–2024 at the Geneva conference in November 2020.

That support was 20 per cent lower than what was pledged at a 2016 conference and is unlikely to make its way to the country until confidence returns through the restoration of security, political and economic reforms, anti-corruption measures and adherence to international laws.

Any emerging government under the Taliban needs to “maintain better international relations” to help the economy grow and attract investment, said Haji Obaidullah Khail, chairman of Afghan Business Council in Dubai.