Rounds one and two of the energy contest go to the western alliance: Europe has survived the Russian gas cut-off, and its ban on Moscow's crude oil imports has driven down their price, although not volume. The third round began on Sunday, as it prohibits imports of refined products. This is a much more complex, and potentially disruptive, stage.

Russia has historically been a major exporter of petroleum products, the result of refining crude into diesel, petrol, jet fuel and other outputs suitable for end users. In 2021, it sent 149 million tonnes of crude oil and 99 million tonnes of refined products to the G7 countries and Europe. 56 per cent of its crude, but 70 per cent of its product exports, went to the countries now imposing the ban.

In combination with the ban, EU states have agreed a price cap for Russian refined product sales to other countries using European shipping or insurance: $100 per barrel for high-value outputs such as diesel, $45 per barrel for the low-value by-products, mostly fuel oil and naphtha. While crude oil is currently trading around $80 per barrel, the market price for non-Russian diesel is $110-120 given the costs of refining.

The crude oil sanctions have so far barely affected Russia’s volume of exports, but its markets have been diverted from Europe to Turkey, China and, especially, India. Now a few other customers are emerging, but not many are technically able to process large amounts of Urals, Russia’s main export blend.

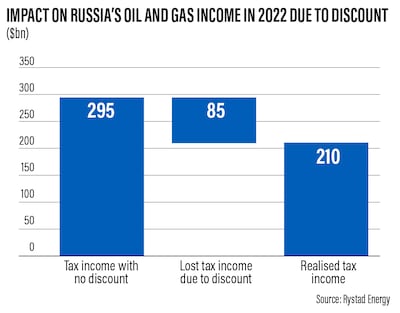

The shrinking pool of buyers, and the increased shipping costs of longer journeys with fewer willing vessels, have led Urals to trade at hefty discounts, more than $30 per barrel below the Brent benchmark last month. That means Urals was selling for about $50 per barrel, well below the $60 per barrel cap. All the capped prices will be reviewed every two months after March. If actual sales prices remain below the ceiling, it could be lowered as if to force Russia to its knees.

Now the Western alliance hopes they can repeat the trick with petroleum products. The aim, as before, is to cut the Kremlin’s revenue without denting its volume of exports too much and causing a politically and economically-damaging spike in prices. Russian diesel is already selling about $20 per barrel under market levels for other countries’ output.

The global refining market has been very tight over the past year, because of the post-Covid rebound in demand, shutdowns of refineries in Europe and the US during the previous few difficult years, and Chinese government restrictions on fuel exports. Last year, the benchmark margin for refining US crude oil reached $60 per barrel, far above the historic average of about $10; it has fallen back but recently rebounded to $42.

Diesel is the key workhorse fuel of the global economy, powering lorries, many trains and ships, factories and backup generators. While air travel was restricted by Covid, refineries could shift their output from jet fuel to the chemically similar diesel, but passenger flights continue to recover, especially in China. Worldwide diesel inventories remain unusually low.

Russia is Europe’s major supplier of vacuum gas oil (VGO), an intermediate product used to make petrol and diesel. It is not clear how the price cap will classify VGO, what other markets Russian VGO could go to, or where Europe’s refineries would find alternative supplies.

Against this, large new refineries are opening or gearing up in China, Kuwait, Oman, Iraq and Nigeria this year, and China has raised its product export quotas. Recessionary fears and the imminent end of the Northern Hemisphere winter may ease diesel and heating oil demand.

Russia’s task in minimising the impact of the oil product ban and cap is both easier and harder than for crude.

More countries can buy Russian products – they can go straight to end users, rather than sophisticated refineries. Latin America and Pakistan have emerged as likely purchasers. Products can be blended to disguise origin, and fuel oil can be burnt in power plants or ships who may not be too inquisitive about the source.

But oil products are typically shipped over shorter distances than crude. Sending large volumes of fuel to Asia will strain the tanker fleet, and vessels cannot switch between “dirty” (crude, fuel oil) and “clean” (diesel, petrol, jet fuel) cargoes without extensive cleaning. Russia could refine less and try to export more crude, but that would risk domestic shortages and require pushing even more Urals into a limited market.

China and India are net importers of crude but net exporters of refined products. Logistical and quality specification issues may prevent them from importing more Russian fuels for domestic use, or processing higher quantities of Russian crude, to export more of their product output to Europe.

If the cap for certain products is set too low, and if the jury-rigged replacements for the complex machinery of Russia-Europe petroleum logistics prove inadequate, shortages will pop up unpredictably – whether in petrol, diesel or jet fuel – and prices for non-Russian alternatives will soar. The complex new Middle Eastern and Asian refineries, producing fuel of European specifications, will benefit.

Some of the extra costs of this hasty replumbing disappear into the pockets of Russian intermediaries – shippers, traders, brokers and insurers. At any rate, most of this probably does not reach Moscow’s tax authorities. And a large part represents the very real costs of overcoming the new frictions in petroleum trade.

Sanctioning oil products is the next step in the Western alliance’s economic counter to Moscow. It is going to be harder to administer and harder to work around than the measures on crude – and that is threat and opportunity for both sides.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis