Art critic Jack Bankowsky once complained that art-fair art is “at least as enthralled with the shop window as it is sceptical of its tyranny”.

In a now infamous essay from 2005, he wrote of an ennui within the art set, who ricocheted between Miami, New York and London, promulgating “the sensational over the substantial”.

Twelve years on, there was little sign of art-fair fatigue at Art Basel Hong Kong (ABHK), where more than 70,000 visitors, museum curators and collectors poured through the doors over five days.

They snake around the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, queuing for hours for the sold-out show in scenes akin to a rock concert.

Art sales globally might be down – sales fell by 11 per cent last year, according to the first Global Market Report released on March 22 by ABHK and Swiss finance firm UBS – but the Asian market has proven more buoyant with collectors looking further afield and becoming increasingly sophisticated in their tastes – a fact that has drawn UAE galleries and those exhibiting Middle Eastern art to the Hong Kong fair in the hope of luring new clients.

ABHK, which ended yesterday, followed hot on the heels of Art Dubai. It is a very different proposition to the Dubai affair. While Art Dubai attracted 95 galleries and is the biggest art fair in the region, ABHK is an international juggernaut pulling in 242 galleries and collectors from around the world.

It is enough of a pull for Dubai galleries, Lawrie Shabibi and the Third Line to pack up their wares and set up shop for the second time in two weeks, this time for a much bigger crowd.

Sunny Rahbar, co-founder of The Third Line, admits: “We are running on empty”.

Her booth contains a mini retrospective of one of her longest-established artists, Iranian Monir Farmanfarmaian, whose mirrored mosaics and 1980s flower drawings attract crowds of snappy-happy visitors.

While there is plenty of interest, closing a deal for works costing up to US$600,000 (Dh2.2 million) is a slower process. “We’ve been thinking of doing this fair for a while and it feels like the right time to introduce the artists we work with to this market,” says Rahbar.

“One reason we hadn’t done it before was its proximity to Art Dubai, as they are back to back.

“We have a very focused programme of contemporary Middle Eastern artists and we did not know if this was something that would work in Asia.

“I am very happy we made the decision to come. We have met a lot of people we would not have met otherwise and there is a huge interest in art here.”

She had noticed more Asian collectors on the scene in Dubai showing interest in work from Middle Eastern artists. “Initially collectors buy the work of artists where they are from but as they become more seasoned and go to see more fairs, they collect outside their nationality,” she says.

Asmaa Al Shabibi and William Lawrie, of Lawrie Shabibi, are suffering from actual fatigue rather than art-fair fatigue, having packed up their Art Dubai booth at 10pm on the final day and flown to Hong Kong less than 12 hours later to start again.

Now in their second year at ABHK, the pair are better versed in what to expect from a big international fair – but playing with the big boys can, nevertheless, be daunting. “I walked into the collectors’ lounge and thought, ‘I don’t know anyone here,” admits Al Shabibi.

Their booth in the Insights section featured seemingly varied artworks from Pakistani artist Hamra Abbas and Iranian Shahpour Pouyan, but united under common concepts of truth, integrity and storytelling.

Abbas's marble inscribed flying carpet, called Please Do Not Step: Loss of a Magnificent Story, begins as a mournful account of a long, arduous journey, a thread that is never concluded at the end of the story.

It is juxtaposed with her miniature paintings of labourers, first captured on camera during her residency in Singapore and then painted on silk, while Pouyan's revisionist digital works on paper from the Persian 10th century epic Shahnameh, known as the Book of Kings, obliterates characters in a bewildering retelling of ancient tales – something the gallerists thought would appeal to the east Asian market. They sold four of Pouyan's digital works on paper on the first day.

“We wanted to do something that is interesting to east Asia and links to this place,” says Lawrie. “There was a lot of east Asian influence in Iran at the time [of the Book of Kings].”

He admits it is always a gamble knowing what visitors will buy. “You chuck something in the air and see where it lands,” he says.

In Dubai, they know who their collectors are and where their interests lie. Hong Kong, where their buyers have hailed from Switzerland, France, China and the US, is less quantifiable.

“It is a completely different experience,” says Al Shabibi, who adds that it takes three years to become established in a market.

Elsewhere in the fair, there was a strong showing of Middle Eastern artists, from the Zilberman Gallery exhibiting a series of sculptures and paintings from Iraqi-Kurdish artist Walid Siti to Tunisian gallerist Selma Feriani showing Nicene Kossentini’s finely inscribed 13th century poetry, where layers of Arabic written over one another become so dense they seem almost abstract.

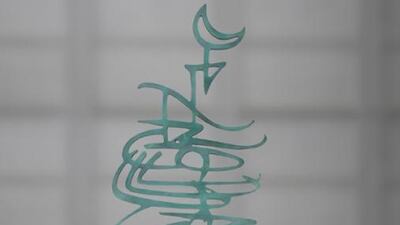

Often, as with Kossentini’s work, Aicon Gallery’s giant Ming-style vases inscribed with Arabic by Rachid Koraichi and Kalfayan Galleries’ ceramics by Lebanese artist Raed Yassin, they seem to blur the line between the Middle East and east Asia.

“We have a very eclectic crowd in Hong Kong, which is very open to works from that part of the world,” says ABHK’s Asia director Adeline Ooi. “We always considered the Middle East to be part of Asia. There is so much in common and we are all quite versed in each other’s forms.”

Projjal Dutta, a partner at Aicon says that just as with any travelling fair, “art is becoming increasingly like music”.

“You do not make money with the album, you make money with the concert tours,” he says.

artslife@thenational.ae