It was a year ago tomorrow - July 24, 2010 - when at least 81,000 people from dozens of countries ranging from Australia to Zambia were doing exactly the same thing - making a short video that captured some aspect of their personal lives on camera. Their hope in doing this was that their video would be seen and shared by the world. For some of them at least, their dream has come true.

The best of their efforts, most of them edited down to one or two scenes, have been compiled in a remarkable film called Life in a Day. By necessity, the selection process was ruthless - the film is 90 minutes long, but the submissions from all those 81,000 people totalled 4,500 hours.

Films: The National watches

Last Updated: 20 June, 2011 UAE

Film reviews, festivals and all things cinema related

Life in a Day is a joint project by the video-sharing website YouTube and Scott Free UK, a company run by the Oscar-winning film-maker Ridley Scott (Gladiator, Blade Runner, Thelma & Louise). The task of assembling and shaping the footage fell to the highly rated British director Kevin Macdonald (The Last King of Scotland).

The documentary would technically be defined as "a user-generated feature film", but that phrase fails to convey what a moving piece of work it is. It's touching and life-affirming; it tells us we have much in common with people everywhere, no matter how far away they live or how different from our daily routines theirs may be.

"There's a touch of We Are the World about the film," Macdonald says with a broad smile when I visit him at his London office.

Through YouTube, Macdonald told people interested in submitting videos: "It will be like a time capsule that people in the future, maybe 20, 30, 40, 50, 100, 200 years, could look at and say wow, that's what life was like." As a starting point, he came up with three simple but telling questions they might like to address: "Who or what do you love most? What are you most afraid of? And what's in your pockets?"

What most surprised Macdonald was the sense of community that can exist on the internet: "I came to realise how generous people were with their time and effort in sending material in. They all seemed incredibly lovely people. It made you feel, hmmm, the world's a pretty good place. There are nice, decent people out there."

Yet the most remarkable aspect of Life in a Day is the ability of ordinary people, untrained as filmmakers, to tell their personal stories so memorably and movingly. The film is full of such examples, and when you talk to people who have seen it, the conversation quickly turns to your favourite segments and theirs.

These include a 90-year-old cowboy in the US state of Colorado, talking colourfully about his life experiences. We watch a barefoot skydiver hurtling towards earth. A man repeatedly dives into a pool, each time with his camera strapped to a different part of his body.

A Japanese father and his young son live together in a chaotic flat - and it becomes clear why it's just the two of them only when the boy says "Good morning" to a small shrine of his dead mother.

An Australian man in a hospital bed, looking gravely ill, struggles to speak, but is desperate to record his thanks on film to his medical carergivers. We see glimpses of the lives of Ukrainian goat-herders, a Peruvian shoeshine boy and a maid in Bali.

This wide-sweeping international dimension was important to Macdonald. Before he requested submissions, he had already guessed it would be relatively easy to attract video content from the western world, especially younger, relatively affluent, technology-savvy internet users, many of whom had already posted videos among themselves. But he insisted that Life in a Day should try to be representative of the planet's different populations, and it was thus necessary to reach out actively to the developing world.

"We bought 400 cheap Fuji cameras, about £80 [Dh470] each," he recalls, "and sent them through various aid organisations. We wanted to be in touch with people who might not hear of the project, who maybe weren't connected to the internet - and in some cases had never handled a camera before. We sent those cameras out to parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America. They were distributed to people in quite remote parts of the world. They got the cameras, and simply sent back the chips.

"Some of the most beautiful material in the film came from all that. It's really extraordinary because it comes from remote parts - the shoeshine boy in Peru, the footage from Bali and a sequence about a Masai woman in Kenya, which I love."

The film's opening scenes swiftly confirm the inter-national nature of Life in a Day. The film's producers chose July 24, 2010 as the day for people to shoot their videos for pragmatic reasons. It was a Saturday - a day off work in many countries. The World Cup, a major global attraction for TV viewers, had just ended. And it was early enough in the summer for many potential contributors not to be on holiday.

But what the producers hadn't realised was that July 24 was a day with a full moon.

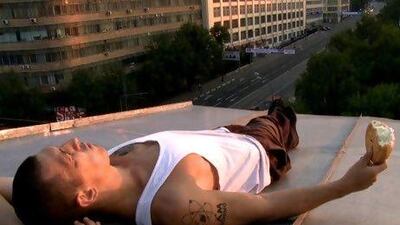

"Of course, wouldn't you know, we got hundreds of clips of it," says Macdonald, pictured above. "So we started the film at midnight, with a dozen or so images of the full moon, shot in different countries." These, he said, included Malawi, South Africa and Australia: "It was a strong, unifying image - the idea that we're all under the same moon."

It then seemed logical for the film to broadly follow the course of the day across the planet. So its earliest scenes show people waking up, stretching, brushing their teeth and preparing breakfast.

Life in a Day flows beautifully and apparently seamlessly - yet the time and effort taken to assemble all the clips submitted was enormous. The film's producers had anticipated about 15,000 submissions and were overwhelmed on receiving more than five times that number. Joe Walker, Life in a Day's British editor, observes: "We had about seven months to get it all done, and no one person can see all that material."

The response to YouTube's invitation had been astonishing. "It was a much bigger task than we'd envisaged," says Macdonald.

So the production hired 23 people, all either film students or people in the media, to go through the submissions and evaluate them.

"Most of these people spoke several languages," recalls Macdonald. "Luckily, London's full of them. We had Chinese and Japanese speakers, and one person who spoke five Indian dialects. For two or three months they all sat in a stuffy little room, and watched the videos for 12 hours a day.

"They'd catalogue them and enter them into a database, noting the visual quality and subject matter. They'd supply some key words and give them an overall rating from one to five." One or two were best, and six was a special category - a clip that was so bad it was amusing. Macdonald and Walker confined themselves to watching the ones, the twos and the sixes.

But the database was a vital tool. If the two men decided they wanted a specific clip, for example, of people brushing their teeth, they'd consult it and find up to 100 contenders among the videos.

Macdonald admits he was not the director of Life in a Day in any normal sense of the word: "Obviously I made a different film from what another director would have. It's about selection. You're always going to express your personal prejudices. But it's more like curating. That's why I share the credit with everyone who sent videos in." (Indeed, the film's end credits contain hundreds of names.)

Intriguingly, Macdonald made his name with documentaries - One Day in September, about the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics (for which he won an Oscar), and Touching the Void, a recreation of two mountaineers high up in the Peruvian Andes who find themselves in mortal danger.

"To me, as a student of documentaries, Life in a Day is very novel and obviously it could only have been made in the last few years," he says. "But it's part of a long line of archive-based films. You take newsreels and archives and shape them into the story you want to tell."

His idea of a shape is meeting with approval, certainly judging by the response to Life in a Day from festival audiences at Sundance, Berlin and South by South West in Austin, Texas.

That's not surprising, given the film's strong feel-good factor. Yet Macdonald insists this was not something he had planned: "Some people have been cynical and said: 'Oh, you've just chosen the nice bits.' But it's not true. We could only work with material that people chose to film, so it was dictated by the kind of people who wanted to take part in this and wanted to be part of the community that made it."

In fact, there's sobering material in Life in a Day. Notably, the production received many submissions from people attending the Love Parade concert that very day in Germany, where a stampede caused the deaths of 21 people and hundreds of injuries. Other people in the film are suffering from chronic illness or even dying. But death and darkness are not the tones that pervade the film. Instead, there's a joyous, almost giddy sense of being alive - even in parts of the world where poverty and hardship look insurmountable to those in more affluent regions.

"It's an unironic film," Macdonald says, "and it somehow allows you to feel empathy for all these people. They all appreciate the same aspects of life - family, children, love. And once you strip life down to those basics, you can't be cynical or ironic about it. Because those things are the building blocks of all of our lives - no matter how sophisticated we think we are."

Life in a Day may be an idea whose time has come. Macdonald recently returned from Jamaica, where he has been putting the finishing touches to his documentary about Bob Marley, and there is already talk about a Jamaican Life in a Day.

And in the UK, he says, the BBC is interested in applying the format to a film about Britain, perhaps to tie in with next year's Olympics in London.

"You never know," he says, smiling, "we may be on to something here."

The UAE segment

The film Life in a Day features an extended clip telling the story of Ayamatti, an Indian gardener living in Dubai. From his modest single room, he talks about how he moved more than 1,600km away from his family to find work, and his gratitude for the life he has found in the city.

"A lot of the submissions were from people who were in positions of power in the world. He was someone who was not," the director, Kevin Macdonald, told The National last month. "He was a very lowly, presumably quite poorly paid migrant worker living away from his family, so he was the kind of voice that probably wasn't that well-represented in the film and is never heard in cinema."

But while Ayamatti might seem like an unusual candidate for film fame, the director says his hopeful outlook was common.

"Largely, what we found was that people were optimistic, even people going through terrible illnesses," Macdonald said. "Ayamatti was somebody who seemed to be at peace with himself and his lot in life - that attitude is what made him attractive."

Life in a Day did not play in UAE but was released on DVD this month.