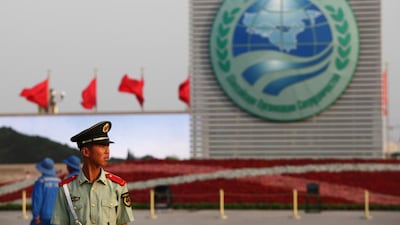

Ten years ago, an unexpected and abrupt rejection of Pax Americana in an obscure part of Asia led to much discussion in foreign policy circles about a “new Nato of the East”. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), made up of Russia, China and four former Soviet Central Asian republics – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan – had originally been formed in 2001, but it was four years later that the outside world sat up and took notice.

In 2005, the United States applied for observer status. This was granted to Iran, India, Pakistan and Mongolia. Not only did the SCO turn America down, however, but at the Astana Summit that year the group issued a communiqué calling for the withdrawal of US forces from Central Asia – and one month later Uzbekistan gave them notice to pack up their airbase at Karshi-Khanabad.

"The leaders of the states sitting at this negotiation table are representatives of half of humanity," said Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev at the opening of the summit, signalling an ambition that regional experts acknowledged. The Washington Times quoted David Wall, of Cambridge University's East Asia Institute, saying that if the SCO expanded to include Iran and other countries, it could be "an enormous power" which "would control a large part of the world's oil and gas reserves and nuclear arsenal. It would essentially be an Opec with bombs".

By the end of the decade, however, as the Russia expert Mary Dejevsky puts it, the SCO seemed “to have vanished from the scene”. In 2007 the US State Department official who oversaw Central Asia, Evan Feigenbaum, was describing the SCO’s list of goals as “ambitious”, and showed how much attention the group was receiving in Washington by admitting to an audience at the Nixon Centre that the SCO “seems to make a lot of Americans’ blood just boil”. Two years later Feigenbaum concluded that “it is hard to point to concrete achievements in many of these areas”.

It appeared, ultimately, to be yet another international organisation that had lots of meetings and made lots of pronouncements but didn’t actually do anything of great significance– until recently, that is. For at this week’s summit in the Russian city of Ufa, the group was due to admit two new members – India and Pakistan. One Chinese official said it was a “milestone” for the SCO, justly, as it was the first expansion in the organisation’s history. And this, according to a commentary on China’s state Central Television website, was just the beginning, saying that “Iran and Mongolia are expected to become full members” while 18 other countries apparently “also hope to become SCO dialogue partners”.

On paper, the SCO could already point to some impressive statistics: its member states occupied “three fifths of the Eurasian continent” and made up about “a quarter of the planet’s population”. With India and Pakistan in the club, Nazarbayev’s grandiloquent “half of humanity” is no longer far off the mark.

In the past, the SCO had cooperated over security, boundary disputes – one of its original purposes – and countering terrorism and extremism, but divisions held it back from becoming the authoritarian counterweight that America feared. When Russia embarked on a short punitive war against Georgia in 2008, China expressed its “concern”, and the then president, Dmitri Medvedev, failed to win the group’s backing at that year’s summit. “Russia wants to be top dog,” comments Dejevsky, and by then it was clear that “it wasn’t going to be top dog in the SCO”.

Since then, however, the two leading members of the SCO have had greater reason to draw together. As the Indian diplomat KC Singh wrote in The Asian Age earlier this month: "Both Russia and China have looming stand-offs with the US and its allies, the former over Ukraine and the latter in the South China Sea. Both wish to redefine the Asian power structure and diminish America's role. Russia's proposed Eurasian Economic Union can mesh with China's 'One Belt, One Road'."

Sino-Russian convergence thus appears to make sense across the board on political and economic levels. The joining of India – historically close to Russia – and Pakistan – to China – helps keep both countries out of too American an orbit, with the possibility of an added peace bonus in the sub-continent. As the former Bangladeshi foreign minister Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury says, the SCO “provides yet another venue for the both of them to interact in. That in itself could be useful”.

On the surface, it might seem entirely possible that, in the words of China’s president, Xi Jinping, “SCO members have created a new model of international relations – partnership instead of alliance”. This would fit with China’s establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a pattern of replacing what a former Russian deputy foreign minister calls “dinosaur structures of the Cold War past”.

Yet there remains a deep scepticism about how much flesh will be put on these new, non-prehistoric bones. Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese Politics at the University of Sydney and a former head of the Asia Programme at Chatham House in London, is doubtful that the revival of the SCO will come to much.

“It was their first stab at building a ‘world away from the US’ in their own backyard,” he says, “but the world has moved on from the SCO. China’s ambitions are now larger and more multifaceted, although I’m sure it will continue to give the SCO all sorts of rhetorical support.

“If it does have a second lease of life, it will be because China lacks a proper entity within which to have a security dialogue with many of its neighbours. This might be a benign way of achieving that. But this would be a hugely difficult, long, hard slog because in security terms, China and its neighbours don’t speak the same language at the moment, and there is no reason to see that problem disappearing any time soon.”

Some analysts believe that Russia is keen to use the SCO to further its ambition of reclaiming “great power” status. But Dejevsky thinks that beneath the glossy talk, there may be little of substance. “Russia has paid more diplomatic attention to China recently, but that seems to be more for appearance – to show ‘the West’ that it has other friends and other options – rather than signalling any sort of serious realignment.”

Ian Bremmer, president of the global political consulting firm Eurasia Group, agrees that the SCO’s influence will remain limited. “It exists as one of many interesting multilaterals where countries can discuss and coordinate away from the western powers,” he says. “But in terms of actually building alternative or competing architecture, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation is not where the action is.”

In truth, the “Nato of the East” label was always hyperbole. The SCO’s joint military exercises were never meant to be construed as aggressive, as Chinese officials pointed out years ago. Indeed, they are on a mission to counter suspicion that there might be anything militaristic about China’s rise.

As Senior Colonel Zhou Bo, director of the Centre for International Security Cooperation at the National Defence Ministry, told the audience at ISIS Malaysia’s Asia Pacific Roundtable in Kuala Lumpur last month: “China is not assertive. China is not aggressive. China just wants to be loved by the international community.”

If the SCO ends up being “seen as little more than a talking shop”, says Chowdhury, “that has its value”. That is true in a continent where peace is still a prize. The SCO may be viewed as primarily a vehicle to serve the interests of its two leading members. But if it also helps promote “jaw-jaw” over “war-war”, we may learn to value it in years to come.

Sholto Byrnes is a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia.