The only voices you hear in Poggio Santa Cecilia are those of the birds. Jays, magpies and flocks of sparrows that start up in surprise as we enter through the town gates. They’re used to having this place to themselves but, on this misty October morning, a small group of us intrude on their space.

Francesco Carlucci, owner of luxury development firm Essentis Properties, is showing me around this ancient hilltop village, which has been deserted since the 1960s. “This is one of the most incredible properties in Italy,” he says, leading me past the red-roofed, stone-and-brick buildings. “The chance to buy a real piece of Italian history.”

For centuries, Poggio Santa Cecilia bustled with life. Blacksmiths worked the forge, farmers came to the grain market to sell their produce, and olives were brought to the town’s press to be turned into oil. But, by the mid-20th century, lifestyles were changing.

The older members of the community began to pass away or moved to modern accommodation elsewhere, and young residents left to look for work in the cities or overseas. The village gradually fell empty and silent, and that same silence still blankets this sleeping beauty today.

That the area has remained so peaceful and undeveloped is astounding, as it is in one of the world’s prime tourism spots. The historic city of Siena, famous for its black-and-white marble cathedral and annual Palio horse race, is just 25 minutes away. Florence is just over an hour’s drive and the beautiful countryside of the Chianti region is on the doorstep.

Owned by a group of five friends for the past 50 years, Poggio Santa Cecilia is now on the market in its entirety for €40 million (Dh166.7m). The price includes the whole village, 20 separate farmhouses with outbuildings, and 1,730 acres of agricultural land, orchards and olive groves, vineyards and woodlands, and two lakes. Having been organically farmed for decades, the land is not only rich and productive, but also offers employment to the local area.

“We first started buying the farmland surrounding Poggio Santa Cecilia with the intention of raising organic cattle,” says Fabio Menegoli, one of the owners. “By the time we had finished we had our own kingdom, and though we never developed the village to its full potential, we have worked hard to maintain it and keep the property together.”

With the owners now ageing and finding the running of the farm harder, they hope to see a new buyer take over the agricultural business and restore the 16th-century buildings. They are adamant that the estate can only be sold as one lot, rather than split, though they understand the challenge and investment needed will be substantial.

Restoration will indeed be a big job, take time and require a committed buyer. The buildings, both those dotted around the farm and in the central village, or borgo, as it is known in Italian, are in varying stages of decay. Many are structurally intact but suffer from crumbling stonework, missing windows, damp and rot. In some areas nature is taking over and the courtyards, alleys and outbuildings are becoming overgrown and undermined by roots and weeds.

Carlucci, whose company specialises in historically accurate construction and restoration work, has been engaged not only to market the site, but also to advise potential buyers on the possibilities of renovation. He will also cost out and undertake the work if required by the new owners.

A developer who builds luxury bespoke villas in Italy, Carlucci is committed to recreating authentic-looking historic architecture, and employs a team of trained craftspeople, including stonemasons and carpenters, interiors specialists and landscape architects. All are dedicated to using local materials and maintaining the essence of traditional design.

Believing that quality work can only be done slowly and with attention to detail, he worries that artisanal skills are being lost. As a result, he has set up an academy for stonemasons in the Basilicata region of southern Italy.

Carlucci believes that it may take around €200m (Dh833.5m) to fully renovate the estate, to repair and rebuild walls and roofs, reinstate windows and doorways, clear and restore the grounds and convert the outdated, unkempt and basic interiors into spaces that are high-spec, contemporary and comfortable. But he thinks the outcome would be well worth the investment.

“The village, once restored, would make the most astounding boutique hotel complex or a fabulous self-contained family home with guest accommodation,” he explains. “It’s not only the space and heritage of the estate that makes it special, but the location, so close to Siena and in the most prime part of Tuscany.”

The borgo is enclosed by the ruined walls of an original 12th-century castle, which once stood on this site. The central buildings date back to the 1500s, and were home to the local estate workers and aristocratic Buoninsegni family, who once owned Poggio Santa Cecilia.

The family became rich through land acquisition and farming and were, according to local historian Doctor Doriano Mazzini, the largest landowners in the Siena region by the 16th century. Poggio Santa Cecilia was also one of the most important Tuscan villages at that time. “The family owned the estate continuously from the 1500s until the 1960s, when it was sold,” he says.

I ask if he would like to see the borgo restored, and he smiles. “Locals are still attached to this place. Many families came from here and we all feel we are suffering while it remains a ghost town. Of course we want to see it live again.”

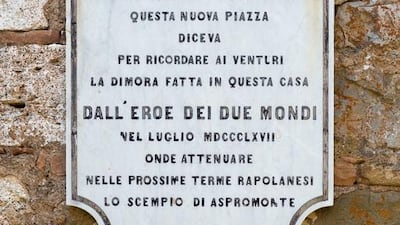

One of the historic high points in the estate’s life was the visit in 1867 of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the celebrated Italian general and politician. A friend of the Buoninsegni family, he stayed at the borgo during one of his campaigns to experience the thermal waters of nearby Rapolano Terme, now a pretty spa town.

A piazza in Poggio Santa Cecilia is named Piazza Garibaldi in his honour. There are also preserved letters from the general to the Buoninsegni family that will be included in the sale.

At the heart of the borgo is the palatial main villa, once home to the Buoninsegnis. The house remains astoundingly intact, with so many original features that it is hard to keep count. Most rooms have panelled or coffered ceilings, some of which are decoratively painted; the main lounge has a stone fireplace large enough to sit in; and, throughout the property, there are arched stone doorways, wooden shutters and tiled floors. Antique furniture and family photos, left in situ when the house was vacated, make it feel as if the owners might arrive back at any time.

The villa is designed with a central vestibule that leads on one side to a two-storey wing with four bedrooms on each floor. To the other side is a series of living areas, including a drawing room and dining room with a dumb waiter. A grand stone staircase leads to the first floor where a vast salon adjoins a glass-walled solarium that runs the full length of the room and overlooks the formal terraced garden, kept neat and lined with citrus trees and oleander bushes.

The basement area of the house is extensive. Carlucci leads me down steps and through dark passageways, which seem to go on for miles, past alcoves and secret rooms, to the cellar where enormous vats, which are more than a century old, still sit. From here there is an escape tunnel, long blocked up, that reaches the edge of the estate. “Think of the possibilities of a space like this,” he says, brushing cobwebs from his face. “It could be a fantastic spa, for example.”

Next to the villa is the church and bell tower, and there is an impressive stable block and carriage room with grand stone columns and large arched windows with lovely views. Carlucci envisions this as a cafe or restaurant with an outside terrace.

As we walk around, the grassy vegetation underfoot gives off the scent of wild mint, and from almost every angle of the village there are stunning vistas across the surrounding fields and rolling Tuscan hills. The main street leads between stone buildings to what was once the central square with its communal well. Sloping off on either side are small passageways and terraces of two-storey houses, some with external relaxation areas, known as loggias, others with far-reaching views. “Imagine these properties fully restored and interior designed. Wouldn’t they be incredible hotel rooms or guest apartments?” Carlucci asks, somewhat rhetorically.

Across the fields, workers tend the fruit trees, heavy at this time of year with plums and apples; the grapes have already been harvested. On our walk to the lake we spy wild flowers that have long since disappeared from many rural areas, and Carlucci says the woods are habitats for boar and deer.

The farmhouses that are included in the sale are in varying stages of disrepair, but all could become fabulous individual homes or holiday villas. We stop to look at one, with a grand arched entrance and decorative rooftop pigeon loft. Where I see overgrown grassland and a house that is falling victim to encroaching brambles, Carlucci sees a spectacular driveway lined with cypress trees and a beautifully restored, elegant villa with a luxurious interior and swimming pool.

What Poggio Santa Cecilia needs is an owner who shares this vision. “Any buyer must have the heart for this project,” says Carlucci, whose desire to see the property restored is evident. “They need to have true passion for it.”

He places his hand on the left side of his chest. “They have to feel it here.”