Here's a question for you: who is the British journalist who has lived in Lebanon for decades, knows the region inside and out, writes weighty and influential tomes about regional politics, takes positions that are controversial in the United States and is not terribly fond of Israel? Most people would point to Robert Fisk, the hot-headed correspondent for The Independent, who has been lionised (and demonised) for his jeremiads against American and Israeli policy. But Fisk isn't the only ageing Briton to have made Lebanon home: David Hirst, in fact, has been there longer, written more books, and - among journalists, anyway - attracted more admiration than the divisive Fisk. Hirst is one of the most respected journalists of his generation, recognised by his peers as an eminently meticulous chronicler of Middle Eastern affairs.

In his recent memoir, Dining with al Qaeda, Hugh Pope - another veteran foreign correspondent in the region - says Hirst was one of the correspondents he respected most, particularly after witnessing a scene in which Hirst, "a slight and utterly unphysical man, evaded his would-be kidnappers in the vital first few minutes by kicking and shouting as they tried to force him from the street into a basement."

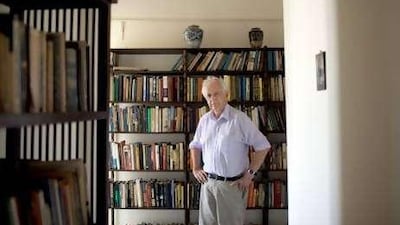

Hirst's demeanour - a slight frame, donnish oversize spectacles on a round head, a quiet, lilting voice and a very English self-effacement reminiscent of John LeCarré's unlikely spymaster, George Smiley - is also the opposite of Fisk's. Max Rodenbeck, the Middle East correspondent for The Economist, says:, "David is the kind of person who will stay silent throughout an animated political conversation for an hour, and then quietly come out with a statement of devastating insight." Still waters run deep, it seems, and Hirst's writings betray a quiet but relentless outrage on behalf of the region he has made his home for over half a century.

Born in 1936 to a middle-class family in England, educated at Rugby, a posh boarding school, at 18 Hirst was sent to do his military service (then still compulsory) in Egypt and Cyprus. Living there between 1954 and 1956, he took the opportunity to travel around the Levant, leaving shortly before the Suez War. "I was a blank slate," Hirst recalls. "I knew nothing about the Middle East and hardly knew the difference between Israelis and Arabs."

Nonetheless, he must have caught some bug. After completing a degree at Oxford, he decided to return to Lebanon, enrolling at the American University in Beirut in 1959, and stayed there when he was offered a job as The Guardian's Middle East correspondent. "In those days, it was a natural progression," Hirst says of his move from the university to the press. Lebanon was "the listening post of the region," and he became fascinated by Arab politics. He would also go on to visit almost every country in the Middle East, get banned from six of them and escape two kidnap attempts. But it may be his coverage of the region's framing story, the Arab-Israeli conflict, that has had the most lasting influence.

At the time, The Guardian was a left-of-centre newspaper with a middle-class perspective, in contrast to the more establishment Times or Telegraph; it had just moved from Manchester to London. Hirst filed his first dispatches to a foreign desk that was still in the northern industrial town, the move still incomplete. The paper was generally pro-Israel, as the British left tended to be at the time, but its new correspondent would play a key role in changing his country's perception of the region.

The Gun and the Olive Branch, Hirst's first book, was a history of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Published in 1977, it was received to a "puzzling silence" in the UK and US and derision by the few reviewers who dared to take a look at it - in part because it came out just after the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's historic trip to Jerusalem. The New York Times even canned a positive review, on orders from on high. Hirst's sin was to have recounted, in great detail, the story of the Zionist project as it had been experienced by the Arabs who necessarily suffered from the ambition to carve out a Jewish state in Palestine. At the time, such criticism of Israel was unheard of in the West, with affection and admiration for Zionism and the narrative of a plucky little state, triumphant against multiple Arab armies only a decade beforehand, the dominant orthodoxy.

As Hirst says in a long essay introducing the third edition - The Gun and the Olive Branch having since become something of a modern classic - he had "set out to 'tell the other side of the story', for the simple reason that, as it seemed to me, it had not been properly told, or won anything like the attention it deserved; I wanted to help redress a balance that was strongly, if not outrageously, tipped in the opposite direction."

More than this, Hirst can claim to have blazed a trail where others - notably Israel's "New Historians" would follow. The nature and extent of Palestinian and Arab suffering at the hands of Israel and the profound destabilisation engendered by the Zionist project are now fairly well understood, and even in the United States it has recently become more permissible to counter the dominant pro-Israel narrative.

In his second book, a biography of Sadat (written with Irene Beeson), Hirst argued that Egypt had sought peace with Israel at the expense of a wider regional resolution to the conflict. The book echoed Arab perceptions of Sadat's "betrayal" of the Palestinians, a view practically absent in the West - particularly when the book was published, shortly after Sadat's assassination, when he was still glorified as a martyred peacemaker. That view of Sadat still persists today, but time has caught up to Hirst's argument, and it is increasingly common to hear laments that Sadat - who originally sought a comprehensive peace deal - mistakenly settled for a bilateral deal or was misled by his Israeli counterpart, Menachem Begin, who was never interested in dealing with the Palestinian question.

The roots of the Hirst's latest book, Beware of Small States: Lebanon, Battleground of the Middle East, came in late 2006, after the war between Hizbollah and Israel that ravaged Lebanon. A publisher asked Hirst to write something on that sad episode, but he demurred. "I quickly gave up the idea, and kept thinking instead of a phrase I had once read: 'Beware of small states'. I looked for the source but did not find it until I searched for it in French, and found out it had been written by Bakunin." With that guiding idea in tow, Hirst wrote yet another broad history of the Arab-Israeli conflict, this time from the perspective of his adopted home, Lebanon.

The warning to which Hirst refers was enunciated by the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin in 1870, in the midst of the Franco-Prussian war, which would lead to the unification of Germany. "Beware of small states," Bakunin wrote, eyeing the German advances, "that are unfortunate enough to possess Germanic minorities in their midst, such as the Flems." Bakunin's context does not transpose straightforwardly to the Middle East, but his warning against the exploitation of identity politics does have resonance.

Before the Great Palestinian Rebellion of the late 1930s galvanised Arab opinion against them, the early Zionists sought an alliance with Lebanon's Maronites, with whom they shared a nervousness about being surrounded by Muslims. Lebanon, a country that now does not even officially recognise Israel, then published tourist guides in Hebrew, and Zionist leaders dreamed it could become "a listening post and propaganda platform for the whole Arab world". The dream of an Israel-Maronite alliance persisted until 1982, when it expired amid the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and the massacre, by Israel's Christian Phalangist allies, of Palestinian refugees at Sabra and Chatila.

But Lebanon's weakness is only one part of the story. For Hirst, the history of Israel has been one of consistent aggression, driven by the need to reassert its "deterrent power" - the ability to inflict wrath on its enemies as to make any resistance not just futile, but positively suicidal. This, at least, has been Israel's standing theory of war since Jabotinsky's Iron Wall. Its current iteration, the Dahiyeh Doctrine - elaborated in Lebanon in 2006 and fully deployed, to results chronicled in the Goldstone Commission's report, in Gaza in 2009 - offers much of the same.

Beware of Small States ends with both a warning and a glimmer of optimism. The warning is that the next conflict in Lebanon - what he dubs the "seventh Arab-Israeli war" - will not be confined to the country. With the prospect of a strike against a nuclear installation, Israel's refusal to discuss the comprehensive peace offered by the Arab League and Iran in 2002, and Iran-backed non-state actors such as Hizbollah and Hamas showing a resilience and defiance long beaten out of the now mostly "moderate" Arab states, the next war may be the first regional one since 1973. This pessimism is only moderated, in the book's epilogue (written in 2009), by a cautiously positive reception of the Obama administration's initial moves in the Middle East.

Speaking last week from Beirut, Hirst tempered that optimism. "Obama has turned to be something of a disappointment," he said resignedly. "He seems to have abdicated and now follows the same failed pattern." Hirst has said his piece - and he'll leave it to others to kick up a fuss. Issandr el Amrani is a writer and analyst based in Cairo. He blogs at www.arabist.net