Looking at her artistic career, it would seem that Monir Farmanfarmaian had two lives – one before exile and another after repatriation.

Born in Qazvin, Iran, in 1922, the artist made a name for herself in the 1960s and 1970s, producing mirror mosaics that fused Islamic geometry and craftsmanship with elements of Western abstract art. When the Iranian Revolution broke out in 1979, Farmanfarmaian and her husband were forced to live in self-imposed exile for almost three decades in New York, where she found it difficult to produce the works she wanted.

Her homecoming in 2004 signalled the rebirth of her artistic career. Over the next decade and a half, she gained recognition as she returned to making elaborate mirror works. This culminated in a 2015 show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and, in 2017, the establishment of her own museum in Tehran. Both were firsts – for the Guggenheim, it was the first solo exhibition for an Iranian artist; for Iran, the first museum dedicated to a single female artist.

By the time she passed away at the age of 96 in April this year, the artist’s legacy was cemented.

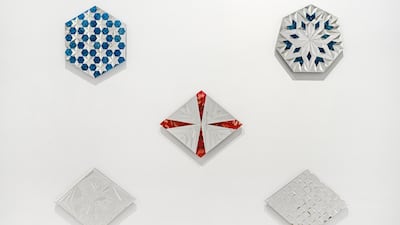

Today, that legacy is being celebrated in an exhibition at the Sharjah Art Foundation, titled Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Sunset, Sunrise, an iteration of a 2018 retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, curated by Rachel Thomas. It presents her famous mirror mosaics, but also her drawings, collages, jewellery and mixed media works, some shown for the first time.

Farmanfarmaian grew up in a progressive family and found she had a penchant for drawing at a young age. She studied fine arts at the University of Tehran and made her way to New York in 1944, enrolling at Cornell University and Parsons School of Design. A career in fashion illustration soon followed. She drew designs at Bonwit Teller, where she worked with and befriended Andy Warhol. Her time in New York was also marked by friendships with other artists, such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Frank Stella.

It was also in the Big Apple that she met and married fellow artist Manoucher Yektai in 1950. The two divorced after three years, and Farmanfarmaian became a single parent to her first daughter, Nima Isham. She eventually remarried in 1957 and moved back to Tehran that year with her second husband, Abol-Bashar Farmanfarmaian, with whom she had another daughter. She set up her studio and continued creating the kinds of floral drawings she had been making since childhood. The next year, her monotypes were awarded the gold medal at the 29th Venice Biennale.

Her trips around Iran proved to be largely influential in her art. Most notable was a visit to the Shah Cheragh mosque in Shiraz, where the interiors are covered in mirror mosaics known as aineh-kari. As light from the hanging chandeliers hit the reflective surfaces, it radiates throughout the space. Farmanfarmaian borrowed from these architectural elements and translated them into sculpture and wall-hung works that took on the form of Islamic geometric patterns.

In 1969, she began producing her mirror mosaics. These pieces seem to emanate light, and the reflections of those looking into them splinter and multiply across these finely-cut fragments. The shimmering, hypnotising works boosted her career as they made their way to the New York art scene in the 1970s. She and her husband frequented the US and were there when they heard news of the revolution. Given her husband’s political affiliations, they knew they could not return to Iran. Back home, their possessions were confiscated, including Farmanfarmaian’s collection of traditional folk art. Her glass paintings and mirror works were destroyed.

After that, the trajectory of her career slowed considerably. Mirror cutters and craftsmen in New York were few and far between, making it near-impossible to create her mosaic reliefs. “She wasn’t as involved in the art world as she always imagined herself to be,” says Darya Isham, Farmanfarmaian’s granddaughter from her first marriage.

“Imagine if you were an artist, and you have one major medium that you are known for, but are unable to do … That’s hard. Despite continuing to draw and create, what she really wanted to do were these mirror mosaics.”

Domestic life also added a set of responsibilities that pulled her grandmother from producing work, adds Isham. “She was very involved in this world of hosting things, being a wife and all the duties that came with that.” Nevertheless, Farmanfarmaian kept creating. She put together a studio space in her apartment and made vibrant mixed-media collages in the 1980s. In these works, which are on view at her Sharjah retrospective, she abandons the angular and measured geometrics of her drawings and mosaics, opting for looser, curved forms made from cut-outs and textile pieces.

At this time, she also produced delicate ink drawings of flora with fluid strokes. “She had this innate ability to draw,” recalls Isham. “She had a very casual mannerism when she was creating … like free-flowing, even though anybody who has ever tried to do that knows it’s anything but casual.”

After the death of her husband in 1991, Farmanfarmaian began making a series of sculptural works she called Heartache Boxes. While the mirror mosaics and collages reveal the brilliance of the artist's mind, these works are insights into her heart. They are also the only works by Farmanfarmaian that are autobiographical in nature. These little boxes of memory, two of which are on view at Sunset, Sunrise, contain memorabilia, old photographs and cut-outs that embody her reflections on home, exile and her artistic practice.

This longing for Iran haunted her during her time in New York. “It was very much a major part of her personality. It was all kind of wrapped up – the story of Iran, how she had to leave … She always talked about summers by the Caspian Sea [where they had a home].” She would talk about their garden, their pool, the dinner parties they had thrown, Isham adds. “Most of the fun memories she had were about the nature, the land and, again, the mosques, the culture, the art and the beauty and all of that.”

Isham, who grew up a few steps away from Farmanfarmaian's apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side, also remembers her grandmother's appreciation for beauty – in any form. "Everything about her life and her apartment – from her garden to the little area she carved out for her studio – it was all very much the ethos and aura of an artist. It was just a given.

"Part of her personality was this great connection to art and nature. Even the things she would do that were not art, were also creative and artistic," Isham adds. "She has this magnificent garden at her apartment and she would tend to the plants, and she would also feed the birds and have this wonderful relationship with the pigeons that would come to her balcony."

Isham also remembers dinner parties when she would help her grandmother cook for extended family. "All the food would be laid out in this beautiful array of dazzling dishes and platters … They always looked so beautiful."

Gallerist Sunny Rahbar, who has had a long-standing relationship with the artist, agrees. Farmanfarmaian’s penchant for beauty and attention to detail were all-pervasive. “Everything is elegant and thought-through,” she says.

Rahbar met her through curator Rose Issa in 2007, three years after Farmanfarmaian permanently moved back to Iran. At the time, Rahbar had just opened her gallery, The Third Line, in Dubai. On a visit to Tehran, she met the artist in her studio. “The door opened and there was a small studio with a lot of light in it,” she recalls. “I saw all these works reflecting the light and, because it was a sunny day, it felt like I walked into a light installation. Monir was bobbing her head [to music] and had this really youthful spirit.”

She was in her eighties at the time, but Farmanfarmaian still had a vitality that drove her to continue producing mirror mosaics with the help of traditional craftsmen. In the 2014 documentary, Monir, by Bahman Kiarostami, we witness the artist's sharp mind at work as she instructs, and at times reprimands, mirror cutters as they materialise her visions.

"I was really inspired by her," adds Rahbar. "Forget about her as an artist, but just as a woman … The fact that she restarted her career at age 81. Most people are like: 'OK, I've lived my life. My kids are grown up. My grandkids are grown up. I'm just going to chill.' She was never going to stop. Even until the very last day of her life, she was still creating work."

It is rare to see artists produce work and receive recognition in old age, which made Farmanfarmaian’s solo show at the Guggenheim in 2015 even more special. “For her, that was a major, major moment,” says Isham. “It was her epitome of modern art. There was definitely a little bit of ‘I can’t believe I’m here’, but, at the same time, ‘I’m finally here’.”

Rahbar remembers that moment, too. “I could just sense how incredibly happy she was. Her whole family was there. We were walking in and I remember looking her, and she was looking at me, and she had this joy of a child. She was so excited.”

The two shared a kinship that went beyond the artist-gallerist dynamic, Rahbar adds. “Monir and I were really good friends. By the end of her life, I would say that she was one of my best friends. I spent a lot of time with her, maybe more time than I did with my other artists.”

Their timelines seemed to converge, with Rahbar growing her gallery as Farmanfarmaian re-established her career. “I was very young in my career when I met her. We just opened the gallery a few years before … Things happen sometimes, and we had to meet. I feel really blessed.”

Towards the end of her life, the artist's mind was still active, although her body was becoming increasingly frail. "I think the only frustration she had was that she didn't have enough time left to do all of the things that she wanted to do," says Rahbar. "She'd always say: 'I still have so many ideas, Sunny … I just dream about everything that I'm going to make, but I won't have the time to do all of them.' I think that was the only frustration, maybe even a regret, because her career was interrupted at so many different points for so many different reasons, including the revolution in Iran, kids, her husband's death and then moving."

Rahbar saw the artist in her home just a few days before her passing. "We were talking and laughing," she says. "I knew somewhere deep down inside that this might be the last time I see her. I kissed her on the forehead and told her I loved her. She looked at me and said, 'I love you, too'." Rahbar heard the news of Farmanfarmaian's death just after returning to Dubai.

The artist may be gone, but her work continues to fascinate. Rahbar and Isham are determined to maintain her legacy in their own ways. In 2017, Isham took over the artist's estate, managing the database of her works. "So much of her artwork was lost or destroyed during the revolution, and then, once she started making it again, there was no database. There was absolutely no record of it. So I basically created that and took over managing her relationships with galleries and museums."

Rahbar continues to work with curators and galleries to show Farmanfarmaian’s work around the world. Currently, she is exploring a collaboration with the Serpentine Galleries in London and its artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist. There are tentative plans to publish the curator’s conversations with the legendary Iranian artist, and to present an exhibition in 2021, along with an unrealised large-scale sculptural project. Farmanfarmaian discussed these ideas with Rahbar while she was still alive, and the gallerist says that she intends to make them a reality.

It seems Monir Farmanfarmaian’s third life has begun.