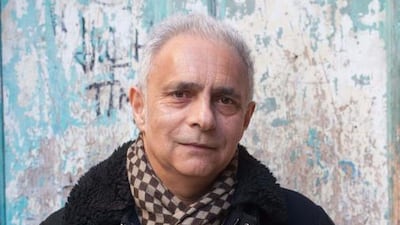

Hanif Kureishi's The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) was one of those audacious, bolt-from-the-blue debut novels that skilfully managed to define an era while heightening our cultural perception of it. Since then he has continued to tackle the issues of identity, social division and race relations in novels, as well as in short stories, plays, films and essays.

His latest offering, Love + Hate, is a collection of stories and essays which covers both familiar ground and new. Those who have made a point of zealously tracking down and reading everything Kureishi has written may be disappointed, as eight of the 15 pieces here have previously appeared in newspapers or anthologies. The rest of us can consistently enjoy a bold and versatile author gliding between fact and fiction to explore the clear-cut dichotomy – and at times blurred distinction – between love and hate.

Of the five stories, three make a lasting impression. “The Racer” is a comic tale about a couple on the cusp of divorce whose last joint-hurrah is a competitive race. Tonally opposite, “This Door is Shut” begins with a mother being brutally expelled from Pakistan by her son and made to start again in Paris. What follows are her attempts to acclimatise, together with her memories of, and a scathing commentary on, the homeland she has left behind: “What other country in the world would hide Osama bin Laden in the centre of a city while pocketing vast amounts of American money to finance the search for him?”

Hovering between black comedy and dark tragedy is the story that kick-starts the proceedings, “Flight 423”. A man flying first-class grows restless, then fearful, as the plane carrying him stays stuck in its holding pattern, performing infinite repetitive loops.

As hours turn into days, food and water supplies run out, toilets overflow and passengers begin to mutiny and even kill themselves. “What a thin membrane it was that kept civilisation and hell apart,” the protagonist remarks.

Kureishi’s essays outnumber his stories, but they also outperform them. There is a sharp-eyed study of “eternal teenager” Kafka (for Kureishi “the paradigmatic writer of the 20th century”) and his fractious relationship with his father. Later, we get reflections on Enoch Powell, the bogeyman who terrorised Kureishi during his adolescent years, and consequent ruminations on racism, “the lowest form of snobbery”.

In a similar vein, a brief but bracing piece on the demonisation of immigrants opens with society’s stoked up prejudices and hysteria before moving on to the author’s own level-headed plea: “Unless we act, he will forever be a source of contagion and horror.”

Rounding out the collection is Kureishi’s sobering account of how a conman swindled him out of his life savings.

For many it will be the various essays on the practice of writing that prove the most absorbing. Not only does Kureishi teach us tricks of the trade, he also shows us deeply personal portraits of the artist as a young man. In “I Am the Future Boy”, a jog with his son takes Kureishi through his neighbourhood and then down memory lane where he ruminates on his own youth in the 1960s and his decision to become a writer: “It was art or nothing.” Other essays on Kureishi’s “calling” touch on the advantages of distraction, the power of imagination and the alternating pleasure and pain derived from the whole creative enterprise.

Whether nuts-and-bolts analysis, soul-searching reportage or stories that straddle the fantastic and the real, the writing within Love + Hate is characteristic Kureishi: candid, stimulating, and uniformly convincing.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance essayist and reviewer.