How can a work of translation become a successful work of literature in its own right? For Philip Kennedy, the general editor of the Library of Arabic Literature (LAL) and the founding faculty director of the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute, and Paulo Horta, assistant professor of literature at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD), the question begins with a set of very detailed and practical literary considerations, but has implications that are far more widespread and profound.

For both men, the practice of translation not only helps to shape the public understanding of Arabic literature, but it also remains a fundamental challenge to the wider understanding and appreciation of Islamic culture in general.

“We have a badly proportioned sense of what Arabic literature is, because there is still so much translation and editing work that needs to be done,” Kennedy says.

Both Kennedy and Horta are also keen to emphasise the collaborative nature of the successful translations they are presenting as part of the Cultural Programme of the book fair this year.

“For some reason there has been a tendency to underemphasise the collaborative nature of translation,” says Horta. “If you just translate a play, even if the poetry is still there, it’s always very difficult to make it work in a new language as spoken text. Instead, we share a belief in the ability to learn from people who know how to make a text sing in translation, which transcends the idea of one person working alone in a room with a dictionary.”

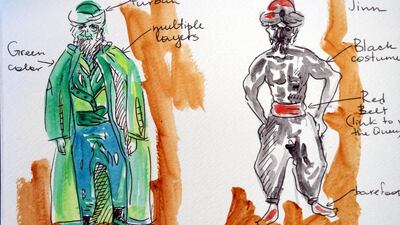

The translation in question is The Jinni Speaks, a one-act play by the Egyptian novelist and Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz. The play is based on The City of Brass, a fantastical tale of magic and jinnis from One Thousand and One Nights. It is the first time the play has been translated into English and both the translation and the reading by Horta and his students are world premieres.

“We have an Emirati student, a Syrian and a Palestinian student who were involved in translating the play, but then we also had theatre majors from both the campus in New York and from Abu Dhabi who were involved in the dramaturgy. The translation was a process that took two semesters of collaborative work,” Horta explains.

“What often happens is that you have people who work on the translation in a purely linguistic manner, from Arabic to English, but then you also have people who cannot read the language of the original text but who can read the language of the theatre and make sure that the text can be spoken.”

The commitment to creating a translation that 21st-century readers can relate to defines the NYUAD rendition of The Jinni Speaks as well as the latest editions from the LAL. These include Humphrey Davies’ translation of Leg Over Leg, a 19th-century satirical work by the Ottoman scholar, writer and journalist Ahmad Faris Al Shidyaq.

“Davies has stepped up with a book that reads wonderfully in the English,” Kennedy explains. “The Arabic sounds totally different to the English, but somehow, the English conveys the spirit of the Arabic. You have to be extremely inventive, inspired and full of energy when you do it, but it is possible.”

For Kennedy and his executive editors James Montgomery of the University of Cambridge and Shawkat Toorawa of Cornell University – both of whom are appearing at the book fair – a collaborative approach to translation is one of the things that defines the LAL, as is a commitment to producing something that is more than just an academic crib.

“We realised that one of the most important genres in pre-modern Arabic is poetry. It’s the pride of the Arabs in a way, so how can we do this library without translating some of that poetry? You don’t want to be married to every single detail. It’s more important to be lean rather than to be comprehensive in certain respects so that in English, some poems ended up reading as English poems in their own right.

“How can you render medieval Semitic poetry into a language that readers in the 21st century now can relate to? I don’t think we’ve had a healthy relationship with translations of classical or pre-Islamic poetry to date. It’s always been very academic and the translations have really been cribs to the Arabic.”

• Philip Kennedy, Shawkat Toorawa and James Montgomery will present the latest bilingual titles published by the NYUAD Institute and NYU Press on Saturday at 7pm at The Tent. A dramatic reading of The Jinni Speaks will take place on Thursday at 5.30pm on the Discussion Sofa

nleech@thenational.ae