American composer, artist and contrarian John Cage once said: “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then 16. Then 32. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.”

It is an idea he lifted from Zen Buddhism, but the concept applies just as well to Boléro, Maurice Ravel's orchestral blockbuster from 1937, in which repetition is undoubtedly the key to its success.

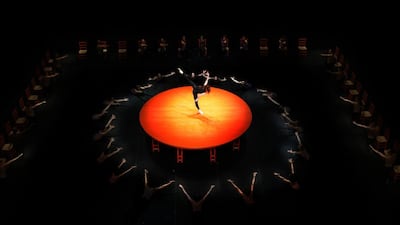

The piece is heard so often in the world’s concert halls that it is easy to forget its origins as a ballet score. It is in this form that it will be staged at Dubai Opera on Saturday, when Swiss ballet company Béjart Ballet Lausanne perform Maurice Béjart’s spellbinding choreography as part of Ballet Gala.

Although the ballet was originally choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska in 1928, following a commission by Russian actress and dancer Ida Rubinstein, Béjart’s intense choreography, created in 1961, has arguably become the most well known.

The psychological drama of both dance and music was so perfect that French filmmaker Claude Lelouch lifted it hook, line and sinker and dropped it into his 1981 epic, Les Uns et les Autres.

However, it is undeniable that the source of the work’s power is drawn from the music.

Unusually, Ravel chose neither to develop nor contrast melodically the languid 16-bar melody he constructed. Instead, it merely loops round and round – 18 times in total.

Of course, being a master craftsman (Igor Stravinsky once compared Ravel to "the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers"), he had more than a few tricks up his sleeve to keep the audience interested. Orchestration is one area in which he excels – conductor and composer Pierre Boulez described Ravel's genius as being his skill in "finding exactly the right colour for a melodic line" – and in Boléro, he deftly employs a variety of instrumental combinations and textures to build suspense until the work's thundering climax.

The composer himself described it in 1931 as “a piece lasting 17 minutes consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music” – something that his snooty critics leap on as evidence of the work’s “poor quality”.

Following one performance, Ravel argued with celebrated conductor Arturo Toscanini, accusing him of conducting it too fast, to which Toscanini reportedly replied: “You don’t know anything about your own music. It’s the only way to save the work.”

Florent Schmitt, a contemporary of Ravel’s, described it as the “only error” in the composer’s career. Yet none of this has diminished the work’s enormous success.

It was an overnight sensation following its Paris Opéra premiere in 1928, and since 1960, it is estimated to have generated a staggering €50 million (Dh203m; unfortunately for Ravel’s estate, the copyright ended this year).

One apocryphal story from the Paris premiere describes a woman, exasperated by the repetition, exclaiming: “He is gone mad.”

Sadly, some experts now think this may well be a possibility. Boléro was one of the last works Ravel finished before his death, which was associated with a brain condition (he died following experimental cranial surgery in 1937).

"Perseveration" is a characteristic found in people suffering from brain conditions such as Alzheimer's disease. It is a word psychologists use to describe the phenomenon where people continually repeat an activity, gesture or a sound in response to a stimulus. The theory goes that the repetition Ravel employed in Boléro was symptomatic of his own degenerating brain – a form of musical perseveration. Certainly, his first recorded symptoms – including memory loss and disorientation – occurred the year before he wrote the work, when he was 52 years old.

If true, it is perhaps one of the saddest stories in the history of classical music, up there with Beethoven’s deafness. Surely it is only a matter of time before someone turns it into a blockbuster film starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley.

Whether influenced by madness or not, the motoric repetition in the music has a profound effect on audiences.

The work made Ravel a star, much to his bemusement – and nearly 90 years after its debut – Boléro is still regularly performed around the globe.

Its curious alchemy has been co-opted by advertising campaigns and filmmakers. Grace Slick, 1960s icon and singer with Jefferson Airplane, said it inspired the song White Rabbit, while Rufus Wainwright rolled it into his song, Oh What a World, in 2003.

It also helped propel British ice skaters Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean to gold at the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics.

At a time where many classical composers were turning away from writing crowd-pleasing works, Ravel was still able to combine innovation with the populist touch.

Boléro also shows he was not half bad at writing a catchy tune.

• Béjart Ballet Lausanne: Ballet Gala is at Dubai Opera on Saturday at 4pm. Tickets start at Dh350 from www.dubaiopera.com

artslife@thenational.ae