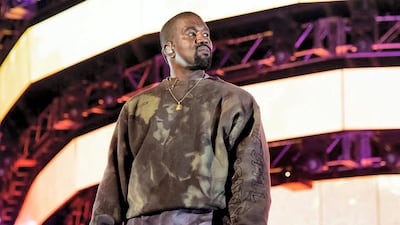

Kanye West wants everyone to know that he found God.

Ever since emerging in April with a series of live impromptu performances, which he called Sunday Service – where West would perform reworked versions of earlier hits with a gospel choir – a picture slowly emerged of a rapper seemingly revitalised.

While West may have once felt his best work stemmed purely from his musical risk-taking – which in part is true – what is perhaps less acknowledged is that his musical genius often arrives when he is at his most focused.

For instance, it takes a certain amount of discipline to meld baroque strings with squalling rock guitars and propulsive rhythms, as he did on plenty of songs from his 2014 masterpiece, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

However, as a result of his fraying mental health (which he later attributed to a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder) and his knack of making unsolicited controversial comments in a public forum, West then dropped the creative ball, and the chaotic albums of the last six years only offered glimpses of the creative genius he claimed to be.

But West says that all of that is now in the past. Seemingly powered with the zeal of a new convert, he dropped his latest album, Jesus is King, last week.

In true West fashion, he declared it a monumental piece of work, while lambasting secular hip-hop songs (and his role in creating them) for their soul-destroying subject matter. He also said he was now "a new Kanye".

The only thing is, however, is that it is not a monumental piece of work at all.

While the album is sonically beautiful and a tight collection of Christian rap songs, it is actually more of a retread than a step forward.

Ever since emerging in 2004 with the epic Jesus Walks, West has always been elaborating about his faith, whether it is about him as a seeker (Never Let You Down) or a sinner (I Am a God).

The relatively muted reaction he is presently receiving for Jesus is King is not down to the sincerity of his actions, but to how West is delivering his message of salvation.

If there is anything the last 50 years of pop music has taught us, it is that fans don’t like to be hectored. They are willing to accept their heroes’ change of lifestyle and artistic focus, as long as it is not rammed down their throats.

This is something Bob Dylan found out when his conversion to Christianity spawned a trio of albums – 1979’s Slow Train Coming, 1980's Saved and 1981's Shot of Love – that remains his career nadir.

Once again, there was nothing wrong with the sentiment. But the awfully po-faced lyrics and uncompromising vision (“You either got faith or you got unbelief and there ain't neutral ground”, from Precious Angel) made it hard to believe that this was the same person who penned some of the most poetic songs in rock history.

While Dylan eventually abandoned the evangelism after his 1983 album, Infidels, he still managed to successfully convey his spiritual outlook through the subtle religious imagery of his lyrics.

Perhaps this was something Cat Stevens took heed of when returning to secular music – after 28 years –with the 2006 album An Other Cup.

Now performing under his Muslim name, Yusuf, the British singer-songwriter managed to brilliantly infuse his evocative songwriting with subtle references to his faith.

Yusuf does not hide his belief in Islam from his fans. Instead, tracks such as Maybe There's a World and I Think I See the Light, act as friendly pleas for understanding, as opposed to Dylan’s lyrical sermons of vengeance and salvation.

The success of Yusuf’s career resurgence proves there is a middle ground of infusing faith and music, if an artist is inclined to do so.

When soul music legend Al Green – now Reverend Al Green – returned to secular music with 2003's successful album I Can't Stop, he kept the subject matter clean, while his odes to romance always seemed like they were referring to a bond stretching beyond the earthly plane.

It was a similar case for Prince upon becoming a Jehovah’s Witness in 2001. Fans soon got over the shock of the Purple One no longer performing his more scandalous songs again after the steady release of even more funk-tastic songs and albums.

Alternatively, one can take a leaf out of the late Leonard Cohen’s book of wisdom. While the Canadian singer and poet never hid his Buddhism in interviews, he nevertheless wrapped them in songs in such an evocative way that fans are still finding new meanings nearly three years after his death.

Whether West will embark on such a route is debatable. One thing for sure is that he needs to dial the histrionics down in order for his fans to cross over with him. If anything, what is the point of faith if it doesn’t teach you humility?