It took almost a lifetime for Kamal Keila to find international success.

Not long before the Sudanese jazz maestro died in Khartoum last Saturday, he had been marvelling at the fact his music was being heard by jazz and funk aficionados globally, being blared from speakers in EDM clubs and at festivals.

He may have been 90 years old when he died of natural causes, but he was in the midst of a career resurgence and a new run of fame. This was down to the rerelease of his critically acclaimed debut album and having a song sampled by hit UK dance group Disclosure.

Jannis Sturtz, head of record label Habibi Funk, also played an instrumental role in Keila's late career bloom. The label specialises in releasing albums by vintage acts from the Middle East and North Africa.

In the summer of 2018, the German label released Keila's Muslims and Christians, a compilation of English and Arabic songs composed in the 1970s and recorded for a Sudanese radio station in 1992.

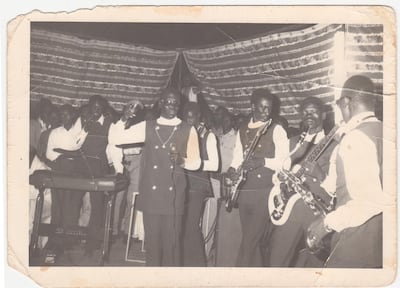

The 10-song set demonstrates why Keila, a singer and composer, was viewed as a leader of Sudan’s vibrant jazz scene in the 1970s, with fans describing him as the country’s equivalent of James Brown and Fela Kuti.

They were not too far off.

That album's title track, along with African Unity, exhibit hot horn flourishes and thick basslines that the Godfather of the Funk would have approved off, while the polyrhythmic drum patterns and circular guitar riffs in Ya Shaifni and Taban Ahwak show that Keila was paying attention to what Kuti was doing when forming the sound that was to become Afrobeat.

That Keila’s songs saw the light of day was a minor miracle.

Speaking to The National, Sturtz recalls travelling to Sudan in the summer of 2017 to research the country's jazz and funk scene. With a plan to release lost recordings by groups from these music genres, Sturtz remembers Keila's name mentioned reverentially by Sudanese friends and musicologists.

“I managed to find only one song of his on YouTube and I remember finding it really interesting,” Sturtz says. “Also the people I met were drawing all these parallels between Keila and what Kuti was doing and I realised that I would love to meet him.”

A quiet man with powerful songs

When Keila, already retired for the best part of two decades, heard a record label head wanted to catch up, he put the kettle on and welcomed Sturtz with a little scepticism.

Sitting in his modest home on the outskirts of Khartoum, where he lived alone with a few pigeons he nursed as a hobby, Keila was a man of few words, recalls Sturtz.

"He has been in the business for a long time so I think he was already trying to manage expectations about our meeting," Sturtz says. "And then, when he told me had original reel tapes at home of a performance on a Sudanese radio station that was almost 30 years old, I was excited."

That happiness soon turned to dismay when Keila emerged from the back of the house with the dilapidated tapes.

“They looked horrible, mouldy and a little wet,” Sturtz says.

"I didn't know if we could salvage what was there. So, I decided I wouldn't listen to it in Sudan but once I got back to Germany. Normally, you get one chance to hear music in good quality from an old tape, so I decided to listen to it while simultaneously digitally transferring it."

What Sturtz heard in the Berlin studio blew him away. It wasn’t so much the tight musicianship, which was expected, but for what Keila was talking about in his songs.

The two reel tapes held separate performances. One contained Arabic songs that focused on standard topics such as love and friendship, while the English material was politically charged.

In the track Muslims and Christians, Keila makes calls for the end of the sectarianism that has often been a fault line within Sudanese society.

Over fluttering horns and urgent basslines, he croons “Sudanese people, Muslims and Christians / Sudanese people, Christians and Muslims / Let’s all sing a song for peace.”

In in the strident Agricultural Revolution, Keila subtly lambasts government policy that left generations of Sudanese depending on foreign aid.

“We need an agricultural revolution to find the solution for hunger,” he says in the song’s powerful spoken word intro. “I am feeling hungry but I don’t need nobody to give me something.”

When Sturtz asked Keila if he knew he was playing with fire, considering the songs were recorded a few years after former president Omar al-Bashir took over the country in a military coup, Sturtz says Keila typically demurred.

“This is part of the reason why these songs were specially done in English. There was more freedom in censorship if you were singing in English at the time,” Sturtz says.

"When we spoke about that with Keila, he didn't say that out loud, exactly. But at the same time, he said he didn't disagree with that argument, either. Keila wasn't someone used to discussing these subjects, he really said all he had to say in the music."

A new generation discovering his work

Sturtz used all the songs recorded in those radio sessions, with Muslim and Christians beginning with the five English tracks and ending with Arabic songs.

Upon its release in June 2018 on streaming services and vinyl, the album immediately garnered international attention with the UK's Financial Times and The Times newspapers publishing enthusiastic reviews.

Not long after, Habibi Funk received a message from UK dance group Disclosure who inquired about sampling Keila's vocals for what would be the single Where Do You Come From.

Keila’s initial reaction upon hearing the thumping deep house single, featuring manipulated versions of his croon and grunts, remains a favourite memory for Sturtz.

"I honestly don't think he understood the song because the world of sampling and electronic music was so far away from what he is used to," he says of one of his last meetings with Keila in 2018. "He found it weird and, 'Said this is my voice but I am not singing it," but he was OK with it."

The fact it also came with a relatively healthy pay check allowed the ailing Keila to spend the rest of his days in relative comfort.

While he wasn't a household name in Sudan, or abroad by any means, Sturtz says his death remains a loss.

“As for what his death means for the Sudanese people, I am not qualified to answer that. Time will tell because a new generation can now listen to his music,” he says.

“As for myself, as someone who loves music and what Keila did, indeed it is a loss. I am just happy that we were able to release his music out there and into the world while he was with us.”