"Suede never really felt that we were part of Britpop," says Brett Anderson, the band's former lead singer. "We felt extremely disassociated from it. We pretty much started the entire scene - and then we disowned it."

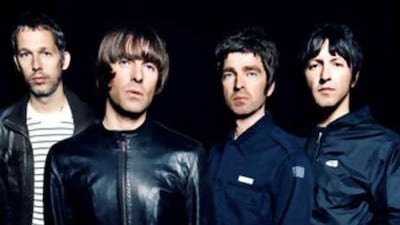

This week, two of the biggest former players in Britpop, the home-grown music scene that dominated the UK in the mid-1990s, have new albums out. Oasis release their seventh studio effort, Dig Out Your Soul, and while a new Oasis album is no longer the major media event that it once was, multiplatinum sales and No 1's across the globe are still guaranteed. The contrast could not be starker with Wilderness, Anderson's second solo album. This muted, minor-key album of acoustic love songs arrives with no fanfare save a handful of decidedly intimate European live dates. With no record label or publishing deal, the singer is releasing it himself.

"I'm delighted with that," says Anderson, still slim and roguish at 40, as he folds his leather coat around him on a chilly London afternoon. "I have no wish to conquer the world any longer as I did with Suede. Back then, I was miserable. Now, as long as I can make records I like, I'm incredibly happy." Happy or not, Anderson's reduced circumstances are deeply ironic, as his bold opening statement is largely correct. Arriving at a time when UK music was still dominated by the Nirvana-led Seattle grunge rock scene, Suede's eponymous 1993 debut album, shot through with melancholy and suburban angst, marked a dramatic cultural shift.

"Everything seemed to be about America," says Anderson. "What I wanted to do with Suede was sing about how I saw the world, which was as a white, working-class nobody living in rented accommodation in London." Suede hit No 1 in Britain and opened the floodgates to the phenomenon that was to become known as Britpop. They were followed by Jarvis Cocker's Pulp, a Sheffield band whose wry songs of provincial yearning had seen them languish in obscurity for 10 years before their moment arrived.

Blur also mined a seam of defiant Britishness, singing of working-class culture and shooting the cover for their Parklife album at Walthamstow greyhound racing track in London. Suede and Blur became arch enemies, particularly after Anderson's girlfriend, the future Elastica singer Justine Frischmann, quit Suede and left him for Blur's frontman, Damon Albarn. Yet a larger nemesis awaited Blur. The Manchester band Oasis arrived on the scene like a juggernaut with their strain of anthemic, melodic rock, which drew heavily on the Beatles. Northern and laddish where Blur were arty and middle-class, they had little love for their southern rivals and soon turned Britpop into a class war by proxy.

The flashpoint of the struggle between the two Britpop titans came in August 1995 when they went head-to-head with the simultaneous single releases of Blur's Country House and Oasis's Roll With It. The question of which record would reach No 1 was so burning that the BBC ran it as a lead item on an early evening news bulletin. Blur ultimately triumphed. Britpop was by now an all-encompassing social phenomenon - but for Anderson, it had already lost its meaning.

"Personally, I was trying to sing about sadness, the poetry of loneliness and the beauty of the everyday, but it all got turned into this thing of, 'Oh yeah, let's sing about going to chip shops,'" he says. "Suede were the first link in the chain, but people destroyed my initial vision and made it into a jingoistic cartoon. So we turned our back on it and made Dog Man Star, an album that was not about little England in the slightest."

By the late 1990s, as egos spiralled and the pressures of sudden fame took their toll, the scene began to founder. In many eyes, Britpop died in 1997 when Oasis unveiled Be Here Now, an album whose unfettered arrogance and bombast made it virtually unlistenable. Since the demise of Britpop, its main creators have experienced vastly conflicting fortunes. After Pulp split, the idiosyncratic Cocker became a ubiquitous media figure, hosting a series on outsider artists for the BBC, directing music videos and curating 2007's Meltdown festival on the South Bank in London. Cocker also wrote songs for the soundtrack for Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire and played a cameo role in the film. Despite having lived in Paris since the millennium, he has become an eccentric British national treasure. However, his eponymous 2006 solo album and a record he released last year under the pseudonym of Relaxed Muscle both sold modestly.

Oasis have continued to fill stadiums around the globe but have seemed stuck in a state of creative stasis since the late 1990s, with each album appearing to deliver diminishing returns on its predecessor. Forever in thrall to the Beatles, Noel Gallagher's musical conservatism has remained stubbornly in place even as his once-majestic songwriting abilities have declined. The Guardian summarised the mood in the UK last week when it reviewed Dig Out Your Soul under the weary headline "While their guitars gently plod". "They sound as if they're killing themselves trying to come up with something that'll do," sighed their critic, Alexis Petridis.

To Gallagher's undoubted chagrin, however, it is Blur's frontman, Albarn, who has proved to be the Renaissance man of the Britpop generation. With Blur in a seemingly permanent hiatus, Albarn has enjoyed critical and commercial success with both Gorillaz, the "virtual" band that he formed with the Tank Girl illustrator Jamie Hewlett, and the dub-inclined The Good The Bad and The Queen, a supergroup whose members include the former Verve guitarist Simon Tong and the former Clash bassist Paul Simonon.

Last year, Albarn again joined with Hewlett to create Monkey: Journey to the West, an audacious Mandarin opera based on a 16th century Chinese novel and featuring a cast of hundreds of Oriental actors, dancers and acrobats. Albarn's inventive soundtrack was lauded by both pop and opera fans alike as the spectacular production opened at the Manchester International Festival and then toured Europe and America.

It would be easy, in the circumstances, to see Suede's Anderson as the Britpop totem whose fortunes have declined the furthest in the intervening years, but it is an interpretation that he fiercely rejects. Now clean living and happily settled, he speaks of having found a new inner peace and independence. "I know not many people will hear Wilderness and it simply doesn't bother me in the slightest," he claims. "It is the first record I've ever made where I haven't had to worry about chart positions or radio play or second-guessing journalists, and I have found that new freedom fantastically liberating. This is exactly the album I wanted to make and, really, what else matters?"

Yet Anderson must inevitably keep abreast of the activities of people such as Albarn and Cocker, his fellow graduates of the Britpop Class of 1995? It is only human nature. The question is hardly asked before it is emphatically rebutted: "No! I have absolutely no idea what they are doing." There's a pause, and an exasperated sigh. "I simply don't care either way. They are just not people who are on my radar."