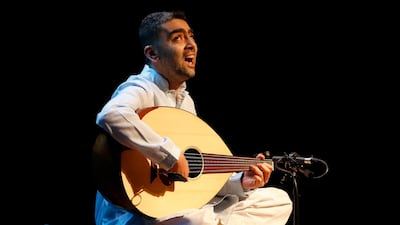

Mustafa Said is the first winner of the Aga Khan Music Awards performance prize.

The Egyptian oud musician and composer emerged victorious among 14 other esteemed finalists, who hail from central and south east Asia, as well as the Middle East, and who all performed a 25-minute set in front of a jury of musicologists and artists. They all competed in three separate heats over the course of three days.

What happened in the finals?

Said’s final set consisted of two pieces, inspired by the Muwashahat music tradition, an Arabic poetic form full of refrains and running rhyme.

The first rendition had him sing a Sufi poem, which dates back more than 3,000 years, to sparse yet complex oud instrumentation. The following piece saw Said pay tribute to a range of Arabic poets, from Omar Khayyam to Khalil Gibran.

Said will take a share of the award's total prize money, which totals $500,000 (Dh1.83m).

And the winner is...

While the winner of the three-day Aga Khan Music Awards was set to be announced before the closing concert on Sunday afternoon, news of Said winning the award was already swirling on Arabic social media.

A source close to the awards confirmed to The National that Said had indeed won the prize and that the musicians were told who won last night so they could prepare for the closing concert.

Who is Mustafa Said?

Abu Dhabi fans will know said from his brilliant and sold-out 2014 Abu Dhabi Festival performance – as the leader of the Asil Ensemble.

Said, who was born blind, learned to read and write music in braille from an early age before studying at Cairo's renowned Arabic Oud House and learning western music composition in correspondence with the US-based Hadley Institute for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Through the Asil Ensemble, said aims to reintroduce the beauty and the complex musicianship of traditional Arabic music to a new generation of listeners.

A reviver of a steep Arabic music tradition

In a previous interview with The National, Said stated the aim of the group was to expand people's knowledge of the form and associated poetry.

“At the moment the prevailing attitude is one of copying,” he said. “If the style is jazz, tango or rock then they will add that on top of Arab classical music. What we are trying to do is develop classical Arab music from within itself by taking from other Arabic music traditions from around the region.”

Who else performed in the finals?

Said was one of a number of finalists hailing from the Arab world, they include a trio of Palestinians: the oudists Ahmad Al Khatib and Huda Asfour, as well as the singer and flautist Nai Barghouti, Lebanese soprano Abeer Nehme and Syrian buzuq player Mohamad Osman.

They each performed in front of a live audience and a jury which included David Harrington, the violinist and founder of the revered experimental group Kronos Quartet, and Nouri Iskandar, composer and former director of Syria's famed conservatory Arab Institute of Music.

Intriguingly, as the presenter announced before the first performances took place, the jury were not looking for pure technical talent. Instead, the panel was more interested in how the artist's work exemplified the award's mission of preserving the cultural heritage of music from the Islamic world.

That lofty aim, not to mention the mixed audience of music lovers and academics, made for a surreal gig for Nehme. Talking to The National after her set – which had the polyglot artist backed by a qanoon player and percussionist, and singing a mix of sacred and folk tunes in Arabic, Aramaic, Amazigh and Greek – Nehme said that she didn't know what to expect.

“I mean, it is an absolute pleasure and honour to be nominated. But this is not my usual kind of performance. I only had two instruments and 25 minutes, so it was really about me giving people something that they can value” she said.

“But you know, being here is actually what matters. As a musician, to be here with all these other wonderful artists from all over the world is really fantastic and rewarding. We made it from over a 1,000 artists, so this whole experience is great.”

An exchange of cultures

It is a sentiment echoed by Mohamad Osman. An instructor of the buzuq at the Higher Institute of Music in Damascus, he said that this was an opportunity to illustrate how the instrument is also part of the Arabic music tradition.

“A lot of the time it is the oud that gets the most attention and that is understandable,” he explained.

"But this instrument is also very important and part of that music universe as well. I try to show that to my students back home and here in front of an international audience.”

Osman hopes the Aga Khan Awards, or another organisation, runs a similar event in the Arab world.

"I do think it is needed because we can show people another side of our culture. At the moment, the market is dominated with these entertainment shows – and that's what they are – that use music," he said.

“Look, I understand that too. There is a bigger audience in that and that means more investment. But these kinds of music events, such as the Aga Khan Awards, is also important and not that big of an investment in the grand scheme of things. You get people to come, enjoy music and learn about their culture.”

And that learning can go both ways, too.

While honoured at the unexpected nomination, innovative Palestinian oudist Ahmad Al Khatib said he came to Lisbon with a point to prove.

"As an oud player from the Arab world there is always an expectation placed upon you by people. People, in both the Arab world and Europe, want to hear the oud played a certain way," he said.

“In the Arab world people want you to play songs they know, while abroad they want to hear that – and I really hate this word – ‘oriental’ sound. I do none of these things because I want to bring the oud out of this museum that people want it in and bring it to the present and the future.”

While Al Khatib’s finals set – a medley of various track that features both surprising riffs and melodies – was short, he deemed it effective in hinting what the oud can do.

“And to make it to the finals of this award shows that perhaps other people want the same thing too,” he said. “People are listening, in some way, and that’s important.”

The details

The Aga Khan Music Awards is being held at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, Portugal and runs until March 31. For more information on the award and the full list of nominees go to www.akdn.org/akma.