Musical classification is a much-maligned practice. Music is a butterfly, floating free, cry critics of labelling - why would you want to pin it to a cork board in a fusty museum? The vast majority of genre names and categories come into existence by accident, when fluid, descriptive, jokey or slang-based terminology calcifies for the sake of easy identification - at least, in these cases, there is no one specific for the critics to blame.

There is one little-known but extraordinary exception to this principle. "World music" as an idea was quite deliberately invented on a Monday evening in June 1987 in a pub in north London. Billed as an "international pop label meeting" for concerned parties, the minutes from the meeting have been kept, and make for fascinating reading.

Gathered that day were 19 record label owners, journalists, radio DJs and enthusiasts interested in music from outside the Anglo-American rock, pop and dance axes, and at that point they faced one major problem: getting the music they loved heard by western audiences. The simple, banal obstacle was that record shops - back when they were vitally important - didn't know where in their racks to place high-life, or cumbia, or raï, or zouk, or anything else that wasn't obviously jazz, rock, dance, or pop as the music retail industry understood it.

These many and varied styles needed an umbrella name to solve this problem - and so, after some debate, the 19 present voted by a show of hands for "world music"; those rejected included "worldbeat", "roots", "international pop", "ethnic", "tropical" and bizarrely, "hot". They launched a world music chart, a world music month, and as large a PR campaign as they could afford. The record shops bought the idea of a separate section.

The committee had a pretty straightforward goal, and they achieved it: to help sell the music they loved in the West. Yet the concept of world music has been problematic like none other in music. The Scottish musician David Byrne spoke for many critics when he wrote in The New York Times in 1999, in a piece headed "I Hate World Music", that it was "a way of dismissing artists or their music as irrelevant to one's own life. It's a way of relegating this "thing" into the realm of something exotic and therefore cute, weird but safe, because exotica is beautiful but irrelevant; they are, by definition, not like us. It's a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of western pop culture. It ghettoises most of the world's music. A bold and audacious move, White Man!"

Ian Anderson, editor of fRoots magazine, strongly rejected the idea that these two words represented the West's latest adventure in cynical or patronising orientalism, recalling the enthusiasm of the 1987 meeting: "Nowhere in any of this was there the faintest whiff of exploitation, exclusivity, cliques, ghettoisation, conspiracies, cultural imperialism, racism or any of the nonsensical '-isms' that have been chucked at the notion, often by people who ought to know better and in the end do little more than expose their own foibles." The message from Anderson and his peers is clear, and pretty persuasive: we've brought incredible music to new ears, made money for its creators, and broadened horizons on all sides - and the only people complaining about it are white liberals wrestling with their post-colonial guilt.

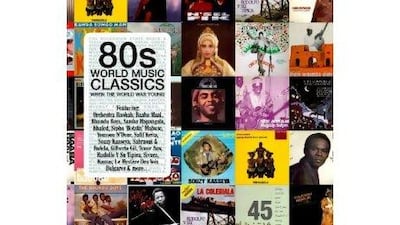

Several of the same names present at that historic meeting in 1987 were responsible for choosing the 26 tracks on a new double-CD collection of 80s World Music Classics. And they really are classics, by megastars such as Gilberto Gil, Baaba Maal, and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. It's a marvellous album, full of household names, legends living and passed, and though most of these records are less than 30 years old, it speaks to a bygone era. The full name for this collection is 80s World Music Classics: When The World Was Young - and the unfortunate choice of subtitle is an encapsulation of every problem people have with the term "world music": that the world outside the West is infantile and underdeveloped - something to be enjoyed and patronised like a small child, not respected like a peer.

Authenticity is part of the world music myth, one of the focal points for its exoticisation. In the introductory sleeve notes to this collection, Nigel Williamson proposes that world music blossomed in the UK and Europe as a response to "fakeness": "As western pop music in the Eighties lost its way in a cacophony of synths and drum machines, discerning music lovers began to look elsewhere for their musical satisfaction," he writes. Because you can't be discerning and like synths, of course.

Yet the idea persists in contemporary pop. The vogue concept in western chart music for the last couple of years has been the use of Auto-Tune, the robot-like vocal filter that removes a singer's idiosyncratic style - it is the very opposite of authenticity in its fetishised form. So where do western musicians look? Overseas, again - one of the hippest indie-rock bands of the last few years, Vampire Weekend, drew on African influences for their first album, and Caribbean for their second. There's no doubt that the internet has revolutionised the global networks that feed into and out of western pop - in contrast to the quasi-anthropological work carried out by some western enthusiasts in the 1980s, who set out to track this music down and "bring it back", like Captain Bligh with his breadfruit.

The distinction between a fake western pop product and an authentic "other" is absurd. In 2011 we do not bat an eyelid at the Portuguese-Angolan kuduro band Buraka Som Sistema being the hippest things in western dance music, incorporating cutting-edge London or New York club sounds into their DJ sets, and playing Rage Against The Machine and MIA too. The Very Best, a collaborative project between two Swedish dance DJs and Malawian vocalist Esau Mwamwaya, began when they met purely by accident as neighbours living in London - and their two albums were some of the most critically revered in recent years. It is no surprise that Syrian dabke sensation Omar Souleyman now plays to large venues in the UK and Europe to the hippest club crowds going.

These trends aren't new to 2011, but they've become more normalised. Sahraoui and Fadela's N'sel Fik was released in 1987 on the Manchester indie and dance label Factory Records - and it fitted perfectly with their aesthetic, just as Buraka Som Sistema's kuduro fits with the house music popular with British dance DJs now. But the best retorts to essentialism or to those fetishising purism (wherever they live) are musical, and Fadela's isn't the only such answer on 80s World Music Classics. Ofra Haza's Im Nin'Alu is a disco anthem of such undeniable greatness that it transcends the world's dance floors: here is a woman from a devout Yemenite Jewish background, taking a 16th century religious diwan poetic form and rendering it zeitgeist-hugging diva club music of the highest order.

Fusion may be a horrible word, but the arguments in its favour have rightly won the day. Ian Anderson tells a story about Youssou N'Dour (whose terrific Immigres appears here) receiving entreaties from an earnest Englishman who hoped he wouldn't "westernise" his sound, like Salif Keita had done with synthesizers. "Youssou politely, gentlemanly, put the guy in his place, saying that instruments don't have a nationality, only musicians, and that if a Senegalese musician played a synthesizer or an electric guitar, it became a Senegalese instrument." This took place in 1987 though, at a time he calls "World Music Year Zero", and it's difficult to imagine a similar conversation happening now.

Saying "the world was young" in the 1980s seems like such a provocative statement on first glance, but as long as "the world" means the world in its entirety, not just the non-western majority of it, it's a fair comment. We've all grown up a bit since these records were first released - the controversy surrounding the making of Paul Simon's Graceland, for example, seems a lifetime away. Much of that western naivete has gone, and it's thanks to the people who sat in a London pub in 1987, and came up with a name so many people love to hate.

Dan Hancox is a regular contributor to The Review. His work can be found in The Guardian, Prospect and New Statesman