Danny Boyle is, he confesses, a little nervous, but it's not the imminent premiere of his latest film, 127 Hours, at the Toronto International Film Festival that is causing his apprehension. After all, this is the city that rapturously embraced his then-unknown Slumdog Millionaire two years ago and sent it on its way to an eventual eight Oscar wins.

No, although he is eagerly anticipating the premiere, what is on his mind much of the time is the 2012 Olympic Games in London and his role in organising the opening ceremony. "You can imagine how nervous I am," he says with a grin. "It's quite a responsibility and there'll be a few sleepless nights and it will probably shorten my life by about five years, but to be honest, I feel very privileged to be asked."

We are talking in a crowded room at the Thompson, Toronto's newest and trendiest hotel where Boyle and his 127 Hours star James Franco, along with Natalie Portman, Carey Mulligan, the new Spider-Man Andrew Garfield and others are guests of honour at a festival party. The Olympic stadium, where the opening ceremony and many of the events will be held, is a mile from Boyle's home in Stratford, East London. "It's very beautiful, like a porcelain bowl," he says. "I can't tell you much about our plans but we're trying to make it a more inclusive Olympics for the spectators. We want to include them more in the Games and make them a part of it but other than that I have to keep it top secret."

We talk again a couple of days later in the more formal setting of a plush hotel suite, although one has the feeling that the affable and outgoing Boyle would be more at ease in a local pub. Earlier, 127 Hours, the intense true story of how climber Aron Ralston had to amputate his own arm after his hand was trapped by a fallen boulder in an isolated canyon, had been screened to rave critical reviews and a highly appreciative audience, who were not put off by the film's graphic scene of self-amputation.

Franco, who is in every scene, gives an Oscar-worthy performance as Ralston, who attended the premiere and cried freely as he watched the re-enactment of his primitive surgical procedure with a blunt knife. As he proved with Slumdog Millionaire, Boyle can take a scene that at first glance looks impossible to film and make it both visually kinetic and emotionally moving. He admits, though, that persuading a studio to back the idea and then filming it proved one of the bigger filmmaking challenges he has faced in his 30-year career.

"I followed the story when it happened because it's one that snags in your brain," he says. "I read Aron's book and then I met him and I had this idea of how to make the movie. I had the idea that we'd make an action movie where the action hero - and he is an action hero because he's super fit - can't move. "I thought it might be entertaining and stimulating if we can get the right actor but most importantly I wanted the audience to be involved in it with him and help release him because otherwise there would just be streams of people walking out saying: 'I can't watch that'."

Boyle, who is returning to England for an Olympics meeting immediately after our interview, knows that if he and his producer, Christian Colson, had not made Fox Searchlight a stack of money with Slumdog Millonaire, 127 Hours probably never would have been made. "When you have the success that we had, you've got to use it," Boyle, who turns 54 on Tuesday, says pragmatically. "It's a window of opportunity and this is the kind of film that a studio would normally baulk at."

Like every film Danny Boyle has made, 127 Hours is totally different from any of his other directorial efforts. While many directors choose the safe path to regular employment by sticking to the tried and tested genre they are known for, Boyle is constantly striking out in new directions and has managed to chart his own, unique path without having to bow to studio pressures. Also unlike most directors, he also likes to film on a low budget rather than have Hollywood's mega-millions at his disposal. His one flirtation with Hollywood in 2000 ended in near disaster when the big-budget The Beach, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and was filmed on location in Thailand, was bedevilled by production delays and environmental protests and was a critical and financial flop. What was worse as far as Boyle was concerned was that it led to a falling-out between him and Ewan McGregor, the actor he discovered, steered to stardom and then, bowing to studio pressure, dumped in favour of DiCaprio for the starring role.

It took five years, a certain amount of pride-swallowing and a humble apology for Boyle to heal the breach. "I think I'm better at making films on my home turf really," he muses. "You learn from experience and I learned that through The Beach. It cost $55 million [Dh202 million] and I found all that money was unbearable. I'm not cut out for that kind of stuff because it doesn't sit well with me. I love seeing big movies but I'm better at making small films."

Born and brought up a Catholic in a working-class area of Manchester, Boyle had a father who was a manual labourer and a devout Irish mother he remembers for her philosophy of believing the best in people. "There was this tramp who used to hang around our area and she used to invite him in to eat and he smelt really bad," he recalls. "But she would look after him. "She and my dad worked very hard to educate me. Someone from my background wouldn't end up as a film director normally, but they let me develop my imagination."

Until the age of 13 he was convinced he would become a priest, but a local clergyman convinced his parents to make him wait until he was 18. By that time he had gravitated towards the theatre and joined the Joint Stock Theatre Company, known for being controversial and for new and cutting-edge plays. In 1982, he moved to London's Royal Court Theatre Upstairs as artistic director in charge of putting on smaller productions. He became the Royal Court's deputy director and then two years later made the leap into television drama, directing among other things two episodes of Inspector Morse and the made-for-television films The DeLorean Tapes and For The Greater Good.

His breakthrough to films came in 1994 when, collecting £800,000 (Dh4.67m) from Channel 4 and a grant from the Glasgow Film Fund, he made the black comedy Shallow Grave. In it he created a number of brilliantly shot comic set pieces that helped to win him several awards. He followed it with Trainspotting, a dark look at the drug-infested Edinburgh underworld that contained some memorable scenes, notably a sequence in which McGregor's Renton dives head first into a public toilet, and his harrowing attempt to quit heroin cold turkey in which the room takes on a fantastic life and character of its own.

With a cult following, Boyle had assured his future in dark, low-budget filmmaking, but instead he made the oddball comedy A Life Less Ordinary and followed it with The Beach. His Hollywood lesson well learnt, Boyle returned to his beginnings to make two television films before hitting the jackpot with his post-apocalyptic horror film, 28 Days Later, a surprise hit around the world. He followed it with Millions, a compelling fantasy about two brothers who find a suitcase full of money, and then shifted genres again for Sunshine, a science-fiction space thriller.

A die-hard Manchester United fan, Boyle arguably has a better track record than his favourite football club when it comes to spotting and nurturing talent. He gave career boosts to McGregor, Christopher Eccleston and Peter Mullan in Shallow Grave and, later, Jonny Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle and Kelly Macdonald to join McGregor and Mullan in Trainspotting. Another two of his discoveries are Cillian Murphy and Naomie Harris, who went on to become bona fide stars following their roles in 28 Days Later.

For Slumdog Millionaire he chose the unknowns Dev Patel and Freida Pinto, who have gone on to star in major movies and who are both at the Toronto festival with different projects. It was perfect casting and Slumdog, with its eight Oscars, including one for Boyle for best director, changed his world. "It was amazing," he says. "We had an extraordinary time and we were offered a lot of different projects we said no to because we wanted to make a film we'd be really proud of... something that was born out of Slumdog Millionaire in a weird way."

But first he and Colson used some of their Slumdog proceeds to provide for the young children who appeared in the movie, and they also inaugurated a wider scheme to help slum children throughout India. They came in for some unwarranted criticism shortly after the movie was released when it was revealed the younger children in it were still living in the slums of Mumbai. in fact the two men used a good portion of the film profits to buy homes for the children's families and to set up a raft of measures to safeguard their long-term future, including a trust fund and sending them to a local school.

"There are many charity things we did to provide for the kids and also we had a responsibility to use some of the profits from the film for a wider scheme that would help slum children in India," says Boyle. "We've been trying to make sure that all goes off well and there are other obligations to meet, too. The funny thing is I can't explain them really but they mount up. "Then we started thinking about what film we wanted to make next," he says. "I talked to Christian about making 127 Hours as an immersive first-person experience in which the audience goes into the canyon and stays there with Ralston, but he wanted it more as a documentary. So I showed him the synopsis I'd written and he agreed we should do it.

"It's a very personal film in a way. It seems funny because he's such a different guy from me," Boyle says of Ralston. "He's from the western states of America, I'm not from there, and he's into the wilderness and I'm an urban person, but there are certain similarities I have with him that I recognise in myself. I think I would apply myself in the way he does with strength and commitment and not losing heart."

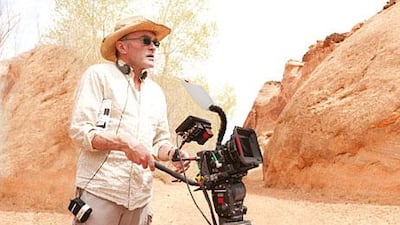

Boyle and his crew spent six days filming at Bluejohn Canyon in Utah, where Ralston was trapped, and then using laser scanning techniques, they created a replica of the site in a warehouse in Salt Lake City, where most of the filming was done. Boyle may be in demand but he is still a down-to-earth, working-class lad at heart and he is occasionally bewildered by the fame and money that have come his way.

"I'm fortunate to have some money and to own my own house so I don't have a mortgage," he says. "It's incredibly liberating because it means you can do stuff that you want to do rather than stuff you feel should do because it will make money. "I'm not very good with money and I don't understand it. I don't like spending huge amounts of it so I try and keep the budgets of the films down." Boyle does not pretend to have any idea about what films will appeal to audiences, although he knows what he likes.

"I don't want to make pompous, serious films. I like films that have a kind of vivacity about them," he says. "I want my films to be life-affirming." And what of box-office success? "You just kind of follow your nose," he says with a chuckle. "You don't think about whether it will be financially rewarding or make you powerful, you just follow the story you want to tell. "Look, I made this film, Sunshine, which I'm really proud of but nobody, I mean nobody, went to see it. There was nothing you could do to make people see that film. And then I make Slumdog and you couldn't stop people watching it. So you just have to continue to make what you feel is honest and truthful and worthy of people's attention. And then hope that it works out."

For Danny Boyle, it is a philosophy that has so far worked out remarkably well.

'Chop your arm off, do it now!'

It sounds like a Japanese reality TV show or a motivational exercise gone wrong: climber gets his arm stuck in a rockfall. Does he wait for rescue or can he free himself? Unable to move his arm, he waits for rescue. Five days later, having drunk all his water, delusional and dehydrated, he levers his arm against the rock, breaking the bones like a chicken leg.

Then he takes out a $15 pocket knife and hacks off the ligaments, leaves his hand and lower right arm under the rock, scales down a 19.8-metre sheer wall with blood dripping out of his elbow and walks out of Bluejohn Canyon in Utah. At the car park he runs into a couple from the Netherlands, who give him water and a couple of Oreo biscuits. No doubt that helped. Aron Ralston's action is the stuff of nightmares. You can watch him on YouTube, where he gives a deadpan account of cutting off his arm with a blunt knife.

"It slid in like I was sliding it into a pack of warm butter... as my hand was decomposing after five days," he says. "Finally the bottom bone snapped with a 'pow' sound... next thing I had to do was break the other bone." He tells how he used the smaller blade to stab away at the muscle, before applying a tourniquet and taking pliers to the tendon. He describes it as the happiest moment of his life: "I knew I was not going to die right here. The power of that was astonishing."

Now a motivational speaker ("Chop your arm off, do it now!"), he continues to climb mountains, ski and raft. Before his moment of drama - and unbelievable pain - he was a student of French and mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon, a university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He quit in 2002 to climb all of Colorado's "fourteeners", or mountains over 14,000 feet (4,267 metres) high. It was in May 2003 that he was trapped in Utah. His arm was retrieved and cremated, and he later returned to the spot, where he spread the ashes.

He still loves rock climbing. "My prosthetic is the key," he says. "The part replacing my hand includes a climbing pick and adze. I plug the device into my arm and use it for both vertical ice and rock. Then I just switch it out for a claw attachment for belaying and rope management. I feel like I'm climbing as well, if not better, than ever."

* Rupert Wright