Lina Al Abed's Ibrahim: A Fate to Define won El Gouna Star for Best Arab Documentary Film at Egypt's El Gouna Film Festival last week, an award that included a $10,000 (Dh36,700) prize. Last month, it had its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, and this week, it will be screened as part of Palestine Cinema Days, a film event taking place in Bethlehem, Ramallah and Gaza. The documentary tells the story of the Palestinian director's search for the truth about her father, Ibrahim Al Abed, who went missing in 1987.

On the surface, Ibrahim appeared to be an ordinary man with an unremarkable job, who lived in Damascus. But he also had a secret life. Under the alias Rashid he was part of the Abu Nidal Organisation, a Palestinian militant group. Named after its founder, the group had split from Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Liberation Organisation in 1974.

The film begins with archive footage of Arafat giving a speech to the UN General Assembly on November 13 that year, in which he said he envisioned a Palestinian state in which Jews and Muslims lived side by side. He also offered a more conciliatory approach to attaining this goal, using peace talks rather than armed struggle. Abu Nidal's Revolutionary Council rejected the proposal.

After her father went missing, Lina Al Abed would tell her school friends that he was a salesman. "My self defence as a child was my imagination," she tells The National. "Until I finished high school, whenever people asked me about my father, I pretended he was still around. I would say he was away travelling and he brought me things back. I understood later that it was my defence mechanism to understand this trauma."

The family continued to live in Syria. "I was 14 or 15 when I started to see my mother in the laundry room, where she was reading from this book and crying all the time," Al Abed says. The book was Patrick Seale's 1992 biography Abu Nidal: A Gun for Hire. In it, Seale says Ibrahim was executed by the Abu Nidal Organisation after they accused him of being a spy for Israeli intelligence agency Mossad and the US's CIA.

"I started doing a journalism course at university and I read the book," recalls Al Abed. "It was the first clear bit of information that I could really find out about him."

But the account given by Seale was contradicted in 1998 by a neighbour of Al Abed's family, who claimed that Ibrahim had returned home after his disappearance, only to leave again in a hurry. "I don't believe that he was a double agent, for the simple reason that if he were, we would have lived in a different way," says Al Abed.

"There is something that is still not clear about what happened, and that is about money and what my father would have done with it."

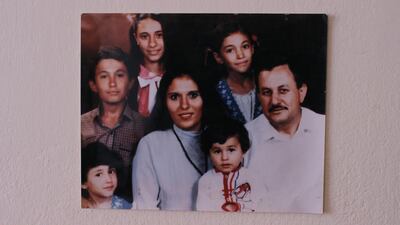

In the film, Al Abed talks to her mother, elder sister and brother, as well as her father's friends, in an attempt to uncover what happened to her father. She asks them questions about how they felt towards him when he left and what kind of man he was. The filmmaker was too young at the time of her father's disappearance to remember him properly. "I didn't make the film as a revision for what happened or to say I was angry," she explains. "I had already reconciled with his absence by the time I started to make the film in 2012. When I was a teenager, I was angry. Later on, I decided I didn't want to speak about it."

Her desire to tell the story grew after she finished making her debut documentary, 2012's Damascus, My First Kiss. "For the first time in my life, I received permission to travel to Palestine. My mother is Egyptian and I grew up in Damascus with a Jordanian passport," she says. "I went to stay with relatives of my father in his village, Deir Abu Mashal, near Ramallah. Those nine days were enough to relieve me from the refugee feeling that I had all my life. I started to ask myself fresh and new self-identity questions. It was then that I knew I was ready to make this personal film."

Al Abed started to develop the project alongside producer and collaborator Rami Nihawi. A year later, in 2013, Al Abed went on a research trip with a friend of her father's in an effort to see his old house and to gather information. Al Abed carried out the central part of the shoot in 2016, which took her to Cairo, Alexandria, Beirut, Amman, Berlin and Deir Abu Mashal.

"I started to notice that although the Abu Nidal Organisation is powerless, it still exists, which makes it hard for people to talk about it," says Al Abed. "But I realised this process is not about the result or destination; it was about the journey itself. When I started editing and deciding how to structure the material, I realised that I would never have this feeling of emptiness that I had in my childhood again. It was like I was holding a big monster inside of me and I finally confronted my fears. Now I'm so happy that I told my father's story."

Palestine Cinema Days starts tomorrow and runs until Wednesday, October 9. More information is at pcd.flp.ps