The camera's lens is pointed at refugees trying to enter Europe in Ai Weiwei's latest documentary The Rest. It's a continuation of the work the celebrated artist, 61, has been creating for a number of years, in which he has been using art to highlight a global crisis.

His endeavours have included gallery work such as Law of the Journey, which featured the creation of a 230-foot inflatable boat carrying faceless refugee figures. In several other shows, Ai has made use of life jackets discarded by refugees fleeing wars in Syria and Libya as they have abandoned rubber boats and landed in Greece. His art has often shown how the material benefits we enjoy in everyday life have come at a terrible human cost.

A direct work on displacement

The Chinese artist – who now lives in Berlin – has visited more than 40 refugee camps around the world since 2015, many of which featured in his powerful feature-length 2017 documentary Human Flow, whichportayed the scale and breadth of the crisis.

The Rest, which premiered at the CPH:Dox festival in Copenhagen last week, is a companion piece to Human Flow, and is in many ways Ai's most direct work on displacement.

It is made up of footage shot as refugees from the Arab world and Afghanistan are stopped or face difficulties at borders in Macedonia, on the Greek island of Lesbos and in Calais, where the infamous “Jungle” saw refugees stranded in tents and makeshift abodes in a no man’s land in their attempts to get to Britain. The documentary is a harrowing humanist work about an urgent crisis.

It also shows the breadth of stories and reactions to refugees. One person carries their cat across borders, a touching human reaction. More brutal is the image of a man trying to rescue a child on a boat whose lungs have been filled with water. The sense of injustice also sees a complaint against a smuggler sentenced to only two months in jail after a rubber dinghy he requisitioned sank, killing 13 children.

The cryptic title, The Rest, has a double meaning. "In making Human Flow we shot more than 900 hours of footage, and I was sorry that I could not use all of it. So we went back to it; this is the rest of the footage," Ai explains. He then gives the more literal and heart-breaking explanation: "The refugee situation is the leftover topic of society – these people are the rest."

Meeting Ai Weiwei

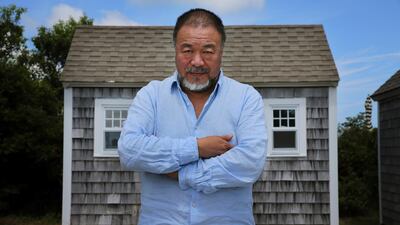

I meet Ai in a hotel lobby in Copenhagen. He's a short man with a huge presence. His beard juts from his jaw, as he sits on one of those impossibly handsome chairs that Scandinavians seem to make for fun. It makes me wonder, what is the human cost for this beauty and comfort?

The softly spoken tells me that supporting refugees has become his life's work. "Since 2015, when we started making Human Flow, we have never stopped filming. This is the second film to come out related to the topic and soon the third one will come out." That future project will see Ai take a close look at the persecution of the Rohingya people, the Muslim minority in Myanmar.

The artist reveals that his interest is not just as an observer – he has let an Afghan refugee reside with him for the past few years at his studio in Berlin. "One of the Afghan refugees I interviewed when we started filming stayed with us. During this long time, at any moment he was facing deportation and this is not an easy process, not everybody can really mentally handle it."

The power structures at work make it difficult for refugees coming to Europe, Ai adds. "The power and the inhumanity is designed to crush you," he says.

The asylum system is a robotic inhumane mechanism, and The Rest also highlights how citizens can complain about the inconvenience to their own lives rather than show compassion. Does he think people in the digital age, where phones are brought to the dinner table, have forgotten the art of interaction and communication? "I think so," he says.

Ai argues that modern life means our species no longer stops to think about greater questions of existence and the meaning of life. "I'm not a religious person," he explains. "But I need ritual and I need practice, certainly. I need inner discourse to reach a certain kind of enlightenment. Topics such as life and death are no longer talked about. We try to avoid talking about it. But in religious institutions people keep going back to that topic."

The drive to meet refugees, the artist says, is due to his own sense of curiosity. "I have to see something to believe it. I have to see the person's eyes and hear the person when they climb out of their boats into the water. What is the sea like? What do they carry? What do they wear? What kind of language do they use?"

Even though Ai braced himself for what to expect, he is never prepared. His reaction is the same to how these men, women and children are treated. "I'm shocked. I'm totally speechless."