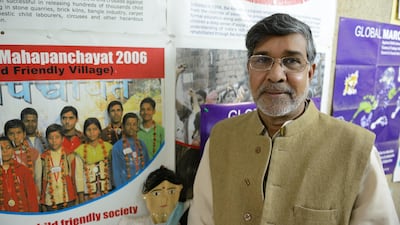

Indian children's rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi is the founder of organisations including Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save Childhood Movement), the Kailash Satyarthi Children's Foundation, Global March Against Child Labour, and GoodWeave International. He has been something of a fixture in the region of late.

Last month, he was in Jordan to speak at the annual summit of the Laureates and Leaders for Children foundation, while this month he was in Abu Dhabi to attend a private screening of the Sundance Festival Grand Jury Prize-winning documentary Kailash, which follows his life and work, at the CultureSummit.

Satyarthi is remarkably unfazed, although clearly quietly pleased, about being the subject of an award-winning documentary from Oscar-winning producer Davis Guggenheim, but when conversation turns to his work for children he becomes far more animated.

The challenges faced by refugee children

Satyarthi notes that the Middle East is a particularly relevant place to be discussing children’s rights at the moment, given the ongoing situation in Syria, as well as recent and continuing refugee crises in places such as Libya, Iraq and elsewhere: “My experience of the experience of children on the move in the Middle East, particularly with reference to the refugee crisis in Syria and elsewhere, is that it is not being paid adequate attention,” he says. “When we talk of the refugee crisis it’s usually quite generalised, but children have to face more specific problems including trafficking, child marriages, child labour, slavery, and more.

“They’re the most vulnerable to becoming victims of further exploitation, whether they’re in refugee camps or outside.”

Satyarthi says that the problem is not confined to the Middle East, but also to other areas of the world where refugees typically flee, in particular Europe.

“About 10,000 children went missing in Europe last year,” he says. “We don’t know where they’ve gone, but they may have been taken by someone with dubious intentions. Jordan was a great place to talk about this last month [at Laureates and Leaders], and we brought laureates, activists and youth from all over world to discuss the issues.”

Raising awareness to make a difference

Satyarthi was a founding member of the Laureates and Leaders for Children foundation, which brings Nobel laureates and world leaders, including King Abdullah of Jordan, Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela Rodriguez and former Irish president Mary Robinson, together to raise awareness around issues affecting children.

The organisation held its first meeting in Delhi in 2016, and it has already achieved some notable results. “That first meeting of Laureates and Leaders had its outcomes and recommendations brought before the G20 summit, and actually incorporated into the G20’s agenda, which was a great result for us,” Satyarthi says.

For Satyarthi, this kind of awareness raising is crucial to the success of his work. “It’s challenging, but once we bring these issues to the public and political discourse, people can’t ignore it so we try to encourage young people in colleges and universities to speak out,” he says.

“We have launched the 100 Million Campaign to mobilise the youth and make them spokespeople and decision makers. Once you raise that strong, loud, moral voice then governments can’t ignore it.”

The one task he would force upon the UN to carry out

Satyarthi has dedicated almost his entire life to his good works. He had a brief career as an engineer at the behest of his parents, but gave it up in 1980 to focus on children’s rights, and his desire to make a difference goes back much farther than that. “For me, this began in childhood, on my very first day at school,” he says. “I saw a toddler sitting outside the school gate with his father, trying to shine shoes. Of course, we didn’t need our shoes shined because it was our first day at school.”

The image struck Satyarthi, and he immediately inquired of his new teacher why the boy wasn’t in school with his other classmates. “He was surprised, but explained that it’s not uncommon for some children to have to work to support their families. The same answer was given by my family and parents, but it just wasn’t convincing me,” he says.

_____________________

Read more:

Malala Yousafzai in Pakistan for first time since she was shot

Plagued by decades of child trafficking, India activists call for crackdown

_____________________

The inquisitive child took it upon himself to ask the boy and his father directly, but the answer still wasn’t to his satisfaction. “The boy was shy, but his father said: ‘I never really thought about it. I started working when I was a boy to support my family, and this is the same. Perhaps you don’t know that we people are born to work’.”

The idea that some children were born to work at the expense of their childhood and education did not sit comfortably with Satyarthi, and when he was 11 he began collecting old books and money to help educate less fortunate children. Indeed, for all the vital work Satyarthi has carried out fighting child trafficking and slavery, it’s this right to education that he sees as the most vital part of his work, and the Nobel prize-winner says that if he could force the UN to carry out just one task to help the world’s children, it would be in the field of education.

“Every child should be brought to a school, now,” he says firmly. “That is simply the most important thing for the whole future of humanity.”

Kailash is due on general release in September or October this year