Analogue filmmaking isn’t part of the memory bank or cultural vocabulary of Generation Z cinephiles. What they know of the visual image is informed by video technology and largely disseminated via the internet. In fact, watching films on a smartphone is no longer brattish behaviour; it is the norm. However, a film renaissance is on the horizon, like a sliver of sunlight glinting through a chink in the curtains, much like at a cinema hall of yore.

Celluloid film, a format that all but vanished in the past decade, is slowly making a comeback of sorts, like a fading diva hoping for a second innings in Tinseltown. A tiny gaggle of filmmakers and artists in India are attempting to keep the format alive through their works and initiatives. In keeping with this trend, Kodak India has even re-opened its film lab in Mumbai, and to much fanfare.

"We are seeing a great interest in film on a global scale," says Vanessa Bendetti, global managing director of motion picture and entertainment, and vice president, consumer and film division at Kodak.

“And there was a need we could fill by opening a lab for local language and international productions in India,” she continues. “There is absolutely a film renaissance taking place, and projects shot on film are garnering a significant amount of recognition worldwide, at festivals and industry award shows. Film matters and makes a difference, and both artists and audiences are responding. As India is home to one of the biggest film markets in the world, we look forward to seeing interest grow in the region with directors, cinematographers and movie-goers alike.”

Why shoot on celluloid?

To some filmmakers, the choice of shooting on celluloid is driven by the themes they choose to explore. Kanu Behl, director of the critically acclaimed criminal family drama Titli, which premiered in the Un Certain Regard category at the Cannes Film Festival in 2014, says, "For better or worse, when making Titli, we knew that our film was going to be boxed in the 'noir' genre, even though the term itself is foreign to me. Yet, for a grainy look that would accentuate the grim milieu we were exploring, shooting on film made sense. More importantly, the decision to shoot on film was not merely thematic or driven by nostalgia. Shooting on film is an emotion. Anyone who grew up watching films projected in a cinema hall [and not beamed digitally] will relate to this feeling."

Some filmmakers have also claimed that shooting on film (which, unlike digital video, doesn’t allow you the prolific freedom of multiple takes of the same shot) brings more rigour to their craft. Actors and crew, for instance, work on a scene with more focus because they are more conscious of how expensive the format is. “To a generation like mine, which knew no better than shooting on film, this discipline is a given. It’s not new to me or my crew because we studied film with film,” adds Behl.

Reframing the Future of Film

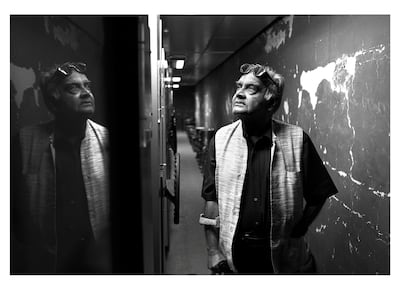

That said, there is a cautious optimism among cultural stakeholders about the future of celluloid in Tinseltown. Filmmaker and archivist Shivendra Dungarpur, a passionate crusader for the cause of India's crumbling film heritage, says there is still a lot of work to be done. In 2014, he set up the Film Heritage Foundation to promote the conservation, preservation and restoration of the moving image. To rally support for the industry in India, his foundation invited Hollywood director Christopher Nolan (of Inception and The Prestige fame) and visual artist Tacita Dean to Mumbai in March this year for an event aptly called Reframing the Future of Film.

"It's a shame how much we have lost of our film heritage. Of the 1700 silent films that were made in India, only nine survive, thanks to the efforts of P K Nair, founder of the National Film Archive of India [Dungapur even made a film titled Celluloid Man in 2012 to salute the pioneer].

While it is heartening to see Kodak open a lab in Mumbai, a lot more institutional investment will be required to create a sustainable infrastructure,” Dungarpur explains. “I am hoping that industry stalwarts and Indian philanthropists are more forthcoming in supporting our cause. Only then can we expect a true renaissance.”

Kodak India is hopeful of creating a buzz around the format.

“Our collaboration with Filmlab will ensure continued colour and black and white 16mm and 35mm processing in the region, as well as upgraded scanning services, lower film stock prices and expanded regional Kodak sales support,” says Bendetti. “Kodak has also formed a strategic alliance with Ivanhoe Pictures in order to identify and support local language and international productions on film in regional markets.”

16mm format is becoming a trend

In April, the National Film Archive of India acquired 71 titles in 16mm format, including Amitabh Bachchan's 1979 blockbuster Suhaag and a treasure trove of Marathi-language classics, a culturally significant acquisition, since it was 16mm films that connected the poor in dispersed locations across India with cinema.

The 16mm format could be easily distributed to the country’s rural nooks, but the city slickers have caught on and film in the 16mm format is becoming a trend. Harkat Studios, an artist collective in Versova in north Mumbai, for instance, held a 16mm film festival this year. Aside from screening movies by filmmakers across the globe, eight artists were also invited to toy with footage sourced from Chor Bazaar – one of the largest flea markets in India – as part of a filmmaking workshop.

In fact, so thrilled is the collective with the result that it is now planning to host a second edition of the festival later in the year. “We are also collaborating with LaborBerlin [a film lab in Berlin, Germany, run by a collective of cinephiles and artists], for a workshop on hand-processing film as part of this second edition,” explains Karan Talwar from Harkat Studios.

Restoring film to its past glory will not be easy, and some might even dismiss these recent twinklings as a passing fad, or a novelty at best. But there is a generation of young people increasingly receptive to the visual medium (though, cynics might even say that in an era driven by social media, visual languages are the only language this generation is conversant with). There is also a significant number of older cinephiles and artists keen to connect with the tactile nature of a format they grew up with. Let there be light.

_______________________

Read more:

Manav Bhalla on his Dubai movie and Om Puri's final performance

Review: Even Anil Kapoor can't save 'Fanney Khan'

Karwaan: A road-trip film that leaves you with a warm fuzzy feeling

_______________________