The cover of Dying Every Day, the latest book from the classical scholar James Romm, features a composite sculpted bust: the Roman emperor Nero and his tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca, the Stoic philosopher, share the same plinth but face, tellingly, in opposite directions. The statue was discovered in 1813, and in reality Seneca is paired not with Nero but with Socrates – a sign of the esteem in which Seneca the philosopher was held – but the driving impetus of Romm's extremely readable and thought-provoking book is that the philosopher's true alter ego was the young emperor whose education he guided – or perhaps the deeper duality belongs to Seneca alone.

Adherents to the Stoic school of thought scorned riches and advancement as the mere baubles of the material world, totally unworthy objects of any serious person’s ambition. Stoics – looking to their great exemplar Cato – prized their freedom to exercise their minds and live simply; in the increasingly sharp gear-work of the Roman Empire, such a lifestyle seemed antithetical to a state service characterised by lavish pomp and slavish devotion to the person of the emperor. True Stoics – as Seneca’s many enemies have pointed out through the centuries – would never deign to enter the cut-throat world of jostling for favour.

A member of the middle “equestrian” rank of the society in his home city of Cordoba in Spain (and the son of a well-known literary figure now known as Seneca the Elder, whom Romm describes as “a tough-minded, rock-ribbed man of letters, still sharp as a tack in his late eighties”), Seneca was a senator under the mad emperor Caligula, who disliked Seneca but refrained from having him executed. He was a minister under Caligula’s successor Claudius, whose third wife, Messalina, convinced him to exile Seneca to Corsica and whose fourth wife (and niece), Agrippina, convinced him to recall Seneca to Rome in order to act as a high-profile tutor to her son Nero.

Romm depicts, in other words, the life of a thoroughgoing imperial toady, and the stark contrast between such a creature and the other Seneca, the public intellectual steadily producing works of Stoic philosophy and literature, has split the ranks of historians and rhetoricians from Seneca’s day to the present. “He had attained both the wisdom of a sage and the power of a palace insider,” Romm writes, “but could the two selves coexist?”

Romm’s hugely enjoyable 2011 work Ghost on the Throne told the story of the successors to Alexander the Great, and in Dying Every Day he continues his examination of the dynamics of power in the ancient world. Drawing on the ancient sources for Seneca’s life and times (mainly Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio) and expertly utilising the last century of Senecan studies (particularly Miriam T Griffin’s extensive and groundbreaking work), Romm attempts to understand the two Senecas and perhaps to meld them.

He sees immediately that both halves of the book-cover illustration are equally important; Seneca’s name is forever linked to that of Nero.

Nero has of course become a watchword of insane tyranny, but it wasn’t always so. The emperor Trajan (like Seneca, a native of Spain), revered by the Romans and sufficiently esteemed by posterity that Dante exempted him from Hell, famously described the “quinquennium Neronis” – the first five years of Nero’s reign – as the pinnacle of imperial success. And many Romans at the time of Nero’s accession at age 18 would have agreed: here was the only surviving descendant of both the golden military hero Germanicus and the deified Augustus, a talented youth of unbounded potential. Romm appreciates that potential – and becomes to my knowledge the first historian to compare Nero to Spider-Man when he writes: “Seneca depicts Nero as an omnipotent but morally serious adolescent. Like a modern teenage superhero, the princeps knows that great powers confer great responsibilities.”

Of course, it notoriously all fell apart. Despite the tutelage and guidance of Seneca, Nero descended into insanity, killing his mother in AD59, killing his wife and her unborn child in 65, subjecting the entire populace of Rome to brutal caprice, cowing the Senate and driving conscientious intellectuals like Seneca’s fellow senator and Stoic Thrasea Paetus into voluntary retirement from public service. Romm characterises this as “the wreckage of the Roman political class”, and in a nice phrase alludes to “the regime’s moral casualties”.

Near the end of his decade in Nero’s service, Seneca described himself as “suffering from an incurable moral illness”, but the central frustration of Seneca is that he was so lax in seeking a cure. He grew enormously wealthy as a result of his close association with the teenager-turned-tyrant, and however much he might extol the virtues of the plain and simple Stoic life in such works as De Clementia (On Mercy) or De Ira (On Anger), Seneca seemed to embrace the sordid as well as the sublime.

“Literary art,” Romm tells us, “that supremely supple tool of which he was a supremely subtle master, could advance him in two ways at once, both as a political player and as a moral thinker.” The political player could engage in “rapacious lending in the provinces” at usurious rates (the calling of such loans in Britain may have precipitated the revolt of Boudica in AD60 or 61) even while the moral thinker deplored the rot seeping through Neronian society – and the clash created a worsening tension in the man who tried to reconcile them.

Seneca actively participated in that rot, and it tortured him. “The leading men of Nero’s age made their way, as best they could, through the moral thicket of the participation problem,” Romm observes. “[Seneca] withdrew only part of himself into a serene world of philosophic contemplation. The other part, the part that had chosen politics to begin with, remained chained to Nero – even though the emperor was rapidly becoming Seneca’s worst nightmare.”

One of the most dramatic episodes of that nightmare was the great fire that swept through Rome in AD64, wiping out entire neighbourhoods and dispossessing thousands of citizens. If Nero is known for any one anecdote, it’s the story of his blithely singing and strumming a lyre (or, anachronistically, fiddling) while Rome burned. The reality is of course much more complex. Nero wasn’t in the city when the fire broke out, but he hurried back and opened his properties (untouched by the fire) to house the homeless and emptied his treasuries to provide relief. But in the aftermath of the disaster, while the serious, responsible Nero was redesigning streets and building codes to make the city more fire-resistant, the egomaniacal Nero was planning the most ambitious palace the West had ever seen, the Domus Aurea, his Golden House, covering more than 100 acres.

It was a sure portent of things to come. “Seneca felt, as he watched the Golden House rise on a mountain of loot,” Romm writes, “that he must get clear of politics without delay. Nero had become an offence to all Stoic principles, an embodiment of luxury and excess.” And in addition to an offence, he’d also become a danger: his paranoia now encompassed everybody. In the wake of a major palace conspiracy (the plotters reputedly tried to involve Seneca, but it seems he was too cautious – or perhaps too loyal to the young emperor he’d helped to raise), Nero ordered his former tutor to take his own life – just as Cato himself had done a century before – and so Seneca was finally confronted with the logical extrapolation of his Stoicism, that it should be easy to let go of life once life has become intolerable.

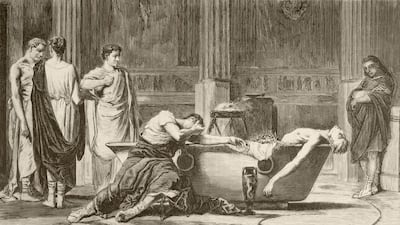

He went home and did it (either his wife volunteered to join him or he dragooned her into it – in either case, she survived). The act wasn’t quick and convenient as it invariably is in the movies; he cut his wrists, but the bleeding wasn’t fast enough; he cut the backs of his legs, but additional bleeding still wasn’t enough; he took a draught of hemlock, but it only made him sick; finally he eased into a superheated sauna and slumped there until the fumes and the blood loss carried him off.

He was an old man when he died and James Romm paints a touching portrait of how worn out he must have been after a decade of negotiating the contradiction at the heart of his life. Dying Every Day dramatises that contradiction wonderfully for a readership more acutely aware than ever of the hypocrisies of political life.

Steve Donoghue is managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.