When Gabriela Maj stepped inside an Afghan women’s prison for the first time, five years ago, she was expecting to be in and out in a matter of hours.

It was her first visit to the war-torn country. A freelance photographer, Maj was not there to document women’s issues in the country or prison conditions. She was there on an assignment to take photos of a subversive Kabul performance artist when she received a call from a French magazine asking her to go behind the bars of the capital’s only women’s prison, Badam Bagh.

She was sceptical that it would even be possible to get inside the jail – but after a week of paperwork and legal wrangling, the Polish-Canadian photojournalist arrived at an unimposing three-storey building, jutting out from the “arid, cracked earth” less than 10 kilometres north-west of the city centre.

When, a few hours later, Maj, 35, who normally splits her time between Dubai and New York, emerged from the prison into the baking June sun, her life set off on a very different course.

The first prisoner she had met inside was Fareshte, a woman her own age who was incarcerated after being raped. She told Maj how, having escaped a stoning by the village elders, a court sentenced her to jail, where she gave birth to a son. The 30-year-old was planning to marry her rapist in exchange for a reduced sentence.

After hearing this story, and others, Maj was moved to spend much of the next five years in Afghanistan, travelling across the war-ravaged land, documenting the tragic stories of women behind bars for offences that the legal systems of most countries would not consider criminal.

Badam Bagh translates as Almond Garden, a beguiling name for a facility that holds more than 200 female prisoners, the majority of whom are reportedly held captive for “moral crimes”. Technically defined as crimes relating to adultery – the crime of “zina” in Sharia – in many cases the women are reportedly guilty of nothing more than running away from an abusive partner, family or an arranged marriage. Other moral crimes include accusations of rape or prostitution.

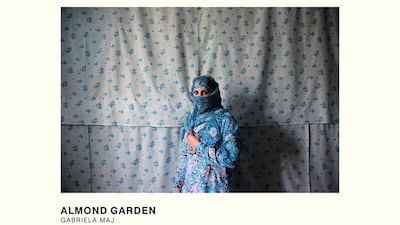

Almond Garden is also the title of Maj's new book, releasing on June 23, which collects the stories and portraits of dozens of female inmates from all over Afghanistan.

“I was deeply moved by the experience of meeting these women,” says Maj, recalling that first afternoon at Badam Bagh. “The stories I heard and the role of the justice system in their lives – it was sort of a funhouse-mirror role in terms of what I understood a justice system to be. These were victims of abuse who are being transformed into criminals. That was something that really stayed with me.”

Between 2010 and last year, Maj estimates she spent close to 12 months in Afghanistan, photographing and recording the testimonies of more than 100 women at eight jails, of whom 75 appear in the book.

A “moral crime” typically carries a sentence of between five and 15 years. Many prisoners are accompanied by their children – but release is not always something to look forward to.

“One of the most common responses I would hear to the question: ‘What will you do when you’re released?’, just over and over, was: ‘I will be killed,’” says Maj. “To be accused of a moral crime is the worst thing that can happen to a woman in Afghan society. These women believe that when they are released, because of the shame they have brought upon their families, [death] is what the repercussion will be for them, and possibly for their kids.”

While it is not unheard of for western journalists to gain access to women’s jails in Afghanistan, typically reporters and photographers go inside for a day, produce a single sensationalised news report and move on.

Maj worked for weeks at a time, travelling alone with only a local female translator. She travelled by plane where possible, or huddled cramped in the back of an old Toyota Corolla, disguised in a burqa or black abaya and headscarf. She spent hour after hour, day after day, getting to know the women, treating them with a respect not found in their own society.

“I always removed my shoes before I went into the cells, which the guards either found hilarious or completely annoying,” says Maj.

“In an Afghan home, if you were not to remove your shoes going into anyone’s personal space, it would be a tremendous insult. This was something little, but something that often set a tone.”

Becoming a confidante to many of the women, Maj came to grasp the inner workings of Afghan jails. Bribery and corruption were rife – cash can buy everything from a larger cell or forged documents to an earlier release or a banned mobile phone.

Maj tells in her book how on “several occasions” she heard from prisoners, wardens and Afghanis alike about the sexual abuse and prostitution of inmates.

Amid conflicting personal testimonies and subjective narratives, Maj chose not to restrict her work to prisoners jailed for “moral crimes”.

In Herat jail she met Nafisah, a woman who was engaged at the age of three, and married at 14. When war broke out the couple, like many others, fled to Iran. Her husband developed a substance addiction and sold her to another man for an evening. So she drugged her husband and slit his throat.

Hearing so many of these stories took a psychological toll on Maj, but she remained driven by more than a desire to complete the book. What, perhaps, began as an aesthetic art project grew into a humanitarian cause.

Maj is working closely with Human Rights Watch and has hosted a series of talks and book launches in the United States and Canada, inspiring coverage from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Vice and the Huffington Post, among others. More events are planned.

“This project was very special to me,” says Maj. “If I was a doctor, maybe I would have expected a moment in life where I felt I was doing something meaningful with the skills that I have – this was that for me.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I don’t think of it as finished by any means – there’s a lot of work to be done with getting the word out about what’s happening to these women. The hope is that this project can contribute to that effort, and effect change in the country.”

• Almond Garden is available from www.almondgarden.net for Dh165. A portion of the proceeds go to Women for Afghan Women, an organisation that runs shelters and provides free legal support and education to incarcerated women and their children in Afghanistan.

rgarratt@thenational.ae

![“One of the most common responses I would hear to the question: ‘What will you do when you’re released?’, just over and over, was: ‘I will be killed,’” says Maj. “To be accused of a moral crime is the worst thing that can happen to a woman in Afghan society. These women believe that when they are released, because of the shame they have brought upon their families, [death] is what the repercussion will be for them, and possibly for their kids.” Courtesy of Daylight Books](https://www.thenationalnews.com/resizer/v2/KYVJBRNCNUGFST6VULUYD4FOSQ.jpg?smart=true&auth=07a4734886ea7202d1aea40cf866b2f3d31f7e63e4512cf2fe8828bcdb282505&width=400&height=225)

![Almond Garden is available from [/URL]](https://www.thenationalnews.com/resizer/v2/VPG4WY2MAHSQVJNLYYQDUUTAN4.jpg?smart=true&auth=1419803ba2f9d42e2233fcfaca6e16a0c71581fc2e27e0ca13eae9a26b2c29b3&width=400&height=225)