Nostalgia makes for plenty of mystery in the present, so what must it have been like for people in, say, 1917? It’s hard to imagine the world they lived in, much less the worlds they longed for. And what if those people were, say, musically virtuosic and Vietnamese?

Obstacles to understanding stack up all the more as specifics come to pass. And yet we can hear strains of such bygone worlds, so disparate and distinct, in sounds that have been handed down through history. It happens messily and chaotically but, also, viscerally – and with inextricable ties to a past that can come to seem both more and less alien over time.

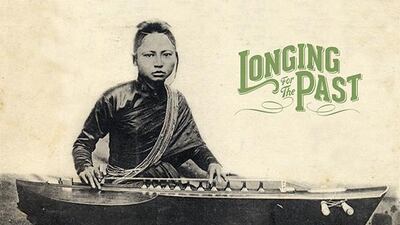

Nostalgia of that very peculiar kind – from Vietnam, via music, circa 1917 – makes up part of the subject of the stupendous new box set Longing for the Past: The 78rpm Era in Southeast Asia. In a handsome hardcover book published with the equally scholarly and collector-centric set, producer David Murray writes of vong co, a type of Vietnamese aria that made listeners in its time pine for memorable worlds that had faded away. The term translates as “longing for the past”, and its moving, thrilling, saddening, solemnising, bittersweet sentiments are in high supply in songs culled from many different styles and many different homes.

Other areas of interest in the book and four-CD set include Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, each surveyed with scarce resources from early records, from as far back as 1906, that remain.

Much like in the rest of the world, the formative years of recording in South East Asia were beset by challenges of considerable kinds. Indeed, an essay on early record-making expeditions in the book makes one wonder how the work could have happened at all. “With oppressive temperatures, monsoons, mosquitoes, fever, dysentery, and language and cultural barriers,” the essay reads, “not to mention hauling hundreds of pounds of fragile equipment and wax masters across the continent, it’s astonishing that these recording engineers were able to overcome the many obstacles before them.”

Yet they did, and in great abundance. With motivation to sell as many expensive phonograph players as they could, early recording companies fanned out to capture as many sounds and styles as ears might stand to hear. Industry pioneers in England, Germany and America sent recordists on boundless adventures around the globe, with tales of bumpy boat rides, dodgy cross-country journeys, and spells in illicit opium dens trailing behind them. In 1902, the British Gramophone Company sent a recording engineer on a storied trip that lasted nearly a year.

It’s worth remembering how exotic their findings would have seemed to the music-minded masses at the time, as many archival images in the set make clear. An old illustration from Laos of a gathering from around 1870 depicts a teeming ritual with staffs of fire burning amid musicians playing strange instruments in a thatched hut – and a lone bearded white man writing things down in a notebook. Or rather, he’s holding a notebook, frozen stock-still, while he stares off in a mix of seeming wonder and disbelief.

Consider, too, how primitive their equipment would have been when machines entered the scene. An old sepia-toned photo shows a band crowding around a tabletop recording apparatus, with a singer angling his voice into the mysterious hole of a metal horn. The best-case scenario would have been a scratchy remnant of a fleshy voice made ghostly and remote – but also profoundly magical in ways we can most likely no longer conceive.

So how does the music sound now? Maybe it’s magical in a different way, or maybe in much the same way, for all we know. In any case, it is in fact magical for all its variety, which shifts between recordings of lavish communal assemblies and singers who sound supremely, cosmically alone.

Longing for the Past opens, fittingly, with a vang co song from Vietnam. Sprightly plucks and sounds from guitar and violin align it with lots of kinds of folk music from all over the world, but the melodies slide through different notes and modes in a manner that is distinctly Vietnamese. From there, the set opens up into limitless vistas of sounds summoned by gamelan orchestras, bamboo flutes, different-stringed fiddles, xylophones, lutes and percussion of alternately booming and tinkling kinds. A comprehensive list of the many instruments heard would stretch on much longer, and then some songs have none at all. As in several others like it, a solo a cappella song from 1930 in Cambodia features a lone male singer invoking what sounds like dozens of different emotions all at once.

Musical styles during the time of these recordings were known to have swirled and blurred. A prehistory in the book, going back 2,000 years before the earliest record included, tells tales of changing empires and revised versions of who was who, in terms of shifting borders and evolving national concerns. “In each case,” it reads, “we know that it was customary for the victors to absorb the court musicians and dancers from their conquests, spreading musical styles and ideas.”

The same goes for music from pretty much everywhere, of course, but it’s a testament to Longing for the Past that a focus on the long view of history feels so relevant and so right. It feels pressing, too. More wisdom from the book, once again from the producer David Murray: “Because of the archaic nature of some of these recordings, I felt it was important to describe the contents in great detail, perhaps more than is necessary for the casual listener.”

It’s an earnest and wry confession for a set that doesn’t stint on the particulars. (Some songs, each given an individual informational inventory, get a page and a half of text in the book.) But more than that, it serves as a bracing reminder of just how easily recordings of the sort could have vanished, died out, disappeared. Most of the records collected are rare, and many of them have barely any verifiable information left to cite. (The text for one, the same Cambodian a cappella song from above, begins: “This recording is from a genre of solo song unknown in the literature today.”)

All the old records are given a good new home, however, in a set that seems as in love with the sounds as it is fascinated with the history behind them. Even though some of the recordings are from as recent a vintage as 1966, the whole of Longing for the Past smacks of an urgent and essential project of reclamation and rescue. Pages upon pages in the book flip through lovingly reproduced images of archaic old labels and logo art. A choice example among many features a drawing of an elephant holding a record aloft in its trunk. Along with those come historical photographs and illustrations of people making music, listening to music and revering music as something much more fundamental and important than a means for mere entertainment.

In mind of that, a pair of songs of Khmer heritage from Cambodia wander through dreamy evocations of down-to-earth life. They date back to 1930, and credits for the artists who performed them are now unknown. More assuredly, they serve as examples of “action tunes” used in stagings of Khmer theatre, to accompany dramatic actions like a simple but seemingly majestic walk in the forest. “Listeners who know the repertory,” the accompanying text says, “can often tell from the music what is happening on stage, even without seeing it.”

Listening can take us a long way, after all.

Andy Battaglia is a New York-based writer whose work appears in The Wall Street Journal, The Wire, Spin and more.