A self-portrait with a difference – this is not a painting, photograph, sculpture or sketch, but instead something more original and more in keeping with its creator's profession. An oval sits in the middle of a piece of white card, like an almond-shaped eye staring out, featuring an elegant wash of Persian lettering in black ink. The writer declares himself the 20-year-old pupil of master calligrapher Sayed Ata Muhammad Shah. Clearly he is learning fast, and how to think for himself.

This man is Sayed Mohammad Daud Hossaini (1894-1979) and this so-called "calligraphy self-portrait" is one of many examples of his craft on view in an insightful new exhibition in Berlin. Calligrapher to the King – Hossaini demonstrates the wide range of the artist's achievements in calligraphy. His self-portrait makes for a fitting starting point. It is more of a signature statement, a calling card that advertises his wares, flaunts his abilities and proves his worth. It is apprentice-work that announces the arrival of an up-and-coming artist, one endowed with a precocious talent. Over the years, he would produce singular results in all shapes and sizes.

Hossaini was born in Kabul. He became a professor of calligraphy, literature and jurisprudence at the university there, before taking up the role of cultural adviser and unofficial calligrapher to the last Afghan king, Muhammad Zahir Shah. A member of Afghanistan’s political and intellectual elite, Hossaini was charged with producing masterpieces of Islamic calligraphy for diplomatic gifts and designing large-scale architectural inscriptions for national monuments, such as the Taq-e Zafar, Kabul’s Triumphal Arch.

He was a prolific artist. Today, however, only a small amount of his vast output survives. Some of his art lies neglected, languishing in distant vaults and dusty archives. The whereabouts of at least 300 calligraphy works owned by the National Archive in Kabul is unknown. Fortunately, and somewhat miraculously, a selection recently resurfaced in the German capital. Hossaini's son, Haschmat, who is based in Berlin, donated a significant portion of his father's work to the city's Museum of Islamic Art in the Pergamonmuseum.

The exhibition, which opened last week and runs until Sunday, May 3, presents for the first time Hossaini's remarkable calligraphy.Some of the exhibits serve a practical function. There is Hossaini's 1932-1933 design for the first official calendar of Afghanistan. It is an intricate and detailed grid network of rows and boxes containing finely penned lettering. The exhibition's curator Margaret Shortle is on hand to decode it. "What makes this calendar interesting is that it is three calendars in one. You get a grouping for each month with three horizontal lines in it like an Excel spreadsheet. The numbers run across. The first line is the Persian solar calendar, commonly used in Afghanistan. Then you have conversions for the Islamic lunar calendar, then the Western Gregorian solar calendar."

Next to this is another work from the same period, also made while Hossaini was the director of the national printing industry in Afghanistan. His design for the industry's official seal reproduces components of the country's national emblem – an image of a mosque, twin flags, and surrounding sheaves of wheat – in clean, precise lines.

The more beguiling displays, however, are those that show Hossaini's creative flourishes. One section is devoted to his experiments with pigment and paper. There are examples of abri – Farsi for clouded or marbled papers – first developed by Chinese artisans in the 10th century, before spreading to Central Asia. Hossaini's grounds are composed of watery swirls and spangled golden light. Some of his patterns seem accidental, resembling oily stains or spillages, but all are aesthetically striking.

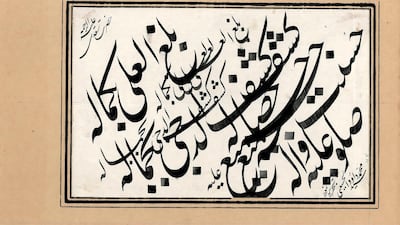

In another section, are Hossaini's examples of siya mashq, or black practice, an artistic form that emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries in Persia, involving the layered repetition of letters. In each sample here, Hossaini's bold black calligraphy makes its mark over faintly coloured marbled grounds.

"Siya mashq is visually dynamic," says Shortle, "but if you know the rules of Islamic or Arabic calligraphy, even when it's done in the Farsi language, it is very strict. You are showing on the one hand [that] you have the artistry to replicate letter forms and letter combinations perfectly, but on the other hand, retaining some sort of dynamic quality so it almost looks like the calligraphy is in movement. You are so good at creating replications that you kind of move beyond stiff repetition."

Elsewhere, the relationship between Persian calligraphy and poetry emerges, the exhibition admiring Hossaini’s lines from important literary figures such as Saeb, Hafiz and Hossaini’s favourite poet, Bidel. Some of the calligraphy visually mimics the rhythm of the poetry. Much of it is written in nastaliq, a script famous for its stretched lines and rounded forms, which matured in the late 15th century in what is today Afghanistan.

The calligrapher spells his native land out at one point – not on one of the mounted pictures, but on a grain of rice in a glass case. The grain next to it is inscribed with a Quranic sura. The artist was kept busy producing these miniature marvels in the 1930s and 1940s, as they were sent to world leaders to strengthen Afghanistan's international relations. Among the letters on display from grateful recipients is one from the office of Adolf Hitler.

Another Quranic sura, the 94th, is displayed on a wall. The beautiful Arabic calligraphy sits within a series of ovals that are themselves surrounded by a decorative rectangular frame. Shortle considers it one of the standout exhibits. “In the four corners, in these clover-like cartouches, you have the names of the first four caliphs. In the smaller ovals, there is Allah and Muhammad. The reason I selected this one is because it looks like it has been printed – it’s ornate and it’s complex. But it hasn’t. It’s all brilliantly done by hand.

"What I find interesting with Hossaini's work, is you have a mix of Persian literature and then you also have a lot of Arab religious elements – a lot of Quranic suras, names of the prophets and Islamic theologians throughout history. These things keep reappearing, again and again."

This exhibition deserves praise for illuminating an overlooked genius and displaying his valuable contribution to Islamic calligraphy.

Calligrapher to the King – Daud Hossaini is running at the Museum of Islamic Art in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, until Sunday, May 3. M ore information is available at www.smb.museum