In 1969, Max Ernst paid a visit to Lebanon to watch a concert by Karlheinz Stockhausen, held inside the newly-remodelled Jeita Grotto. Waddah Faris, at the time a painter and graphic designer, heard about Ernst’s visit and was determined to get a photo of his idol. He bought his first camera and hired a taxi driver to tail the German artist.

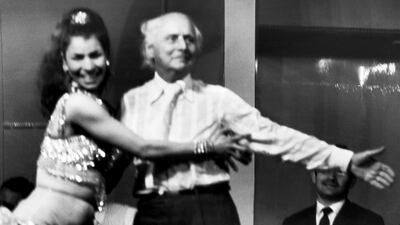

Fortuitously, the two were introduced while relaxing at the St George Hotel, and Ernst mentioned he had not had a chance to see “the real Lebanon”. Faris became his unofficial tour guide, taking him to visit the old souqs, Byblos, Beiteddine, and even to a seedy cabaret so that Ernst could see bellydancers perform.

Throughout their time together, Faris snapped a series of candid photographs of Ernst. It was the beginning of a love affair with photography that has lasted almost half a century.

Between his meeting with Ernst and the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, Faris took hundreds of photographs, most of them portraits. Dozens of these black-and-white images are on show at Saleh Barakat Gallery in Beruit until July 29. Beirut, the City of the World's Desire: The Chronicles of Waddah Faris (1960-1975) pairs Faris' photos with original artwork dating from the same period by Lebanon's luminaries – many of them captured in Faris' photos.

“It took a couple of years to go through the massive photo library that I have,” says Faris, who had developed the negatives from the period but never printed the photographs. He estimates there are more than 100,000 negatives in his archive, of which 5,000 are of a good enough quality to exhibit.

In keeping with gallerist Barakat’s vision for a show reflecting on the artistic community during the period known as Lebanon’s Golden Age, the photographs selected for this exhibition are mostly of prominent art-world figures.

Artists including Mona Hatoum, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Paul Guiragossian, Shafic Abboud and Dia Azzawi; prominent journalists and art critics like Ghassan Tueni, Joseph Tarrab and Helen Khal; and art-world figures like Janine Rubeiz – founder of the famous Dar al-Fan – share space on the walls with theatre-makers including Roger Assaf and Nidal al-Achkar and writers like Hanan al-Shaykh.

Faris’ photographs aren’t simply a collection of staged portraits, however. Shot at candid moments, in natural light, they are intimate and expressive. Faris’ subjects were his friends and contemporaries and their personal relationships allowed him to capture them in all their humanity – laughing, dancing, smoking, sometimes thoughtful or even sad. His portraits of al-Shaykh and Hatoum, in particular, are tender and revealing.

Faris stresses that he wasn’t interested in fame, but simply preserving moments. “When I photographed Mona Hatoum I was photographing the woman that I liked, that I coveted,” he confides.

“That was the reality. It wasn’t that I had a futuristic view of talent. These people I photographed were my friends. I enjoyed spending time with them and I really loved them as people … My friends, as I saw it, all had something particular that I wanted to retain. You have to enjoy people for who they are, not where they are or what they can be.”

As the photographer, Faris is a constant presence in the exhibition – the man at the centre of this Bohemian circle and the eye behind the lens that seeks to capture their essence. Yet he is also notably absent from the show, captured only fleetingly in the mirror and a single playful self-portrait.

“I always consider myself an alien,” he says. “I am Iraqi, Syrian-born, and I call myself a trans-Arab. Wherever I find myself, I have a mission to do something to challenge existing practices.”

Hung alongside his evocative portraits and some of his own work as a graphic designer, are paintings and prints by the artists and their contemporaries. Abstracts by Abboud hang close to early figurative works by Huguette Caland, accompanied by the poster Faris designed when she exhibited in his art gallery, Contact, in 1972. There’s even a portrait of Faris himself, sketched in charcoal by Guiragossian.

Pre-war Beirut is often evoked as a sort of earthly paradise, where wealthy stars sunbathed and swam and partied the nights away. Faris’ photographs go beyond the nostalgia and the mythologising to show real people experiencing day-to-day emotions, and the work they created.

“What I reject in this exhibition is the idea that it’s done for nostalgia,” he says. “It’s not. It’s done to show the mood of me in my time. I like it when somebody comes and asks me, ‘How did you do this portrait?’ I love this question! I try to remember and elaborate on it.”

Rather than the glamorous shots of celebrities partying at the Phoenicia and models sunning themselves at the St George that often crop up in exhibitions about pre-war Lebanon, Faris has selected images that show another side to the country’s history. A series of photographs of Bedouins taken near Baalbek in the Bekaa Valley are among the highlights of the show. Other images capture dance rehearsals in the Bacchus Temple and friends lunching at the Palmyra Hotel.

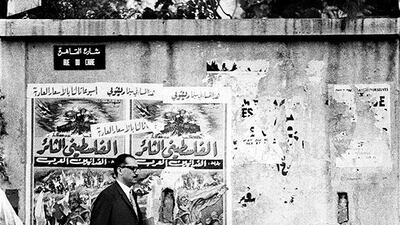

A series of 18 photographs reveal the diversity of 1970s Beirut. Taken from the iconic Horseshoe Café in Hamra, a favourite haunt of artists, journalists, bohemians and academics (now replaced by a branch of Costa Coffee), they are framed around posters for a Palestinian film opening at another vanished Beirut landmark, the Rivoli Cinema.

Over the course of several hours, Faris photographed a series of people walking past the posters, from a man and his dog, to couples in their 1970s attire, schoolchildren and besuited men on the way to or from the office. The series provides insight into the clothes, attitudes and characters of a wide range of locals who share the same stretch of pavement.

Although he rejects the label of “artist” or “photographer”, Faris’s love for the medium is clear when he waxes lyrical about the beauty of black-and-white film, the power of analogue cameras – which he still uses – and the over-saturation of imagery in the digital age.

“Some of the young people come and look at that time and they try to understand it. That’s interesting,” he says of reactions to his work. “But most interesting for me is the guy that only knows how to photograph with his iPhone looking at a different concept of photography and wanting to know how it’s done.”

Beirut, The City of the World's Desire: The Chronicles of Waddah Faris (1960-1975) runs until July 29. Go to www.agialart.com/Exhibitions/barakat_exhibitions