“I am a very stable genius.”

It’s the tweet that sparked countless memes. It’s also the phrase that got Diana Weymar stitching.

Paraphrased from a Twitter thread by Donald Trump in January 2018, it is part of the US President's response to doubts about his mental health. Struck by its strangeness, Weymar, an American textile artist, stitched the words on to an old embroidery work by her grandmother as a way to make sense of them. "I think turning to this medium, especially when it comes to language, is certainly the way I process," she tells The National.

She started doing the same for other Trump tweets, making one or two small pieces a day. But Trump's vitriol was unrelenting, and she found that could not keep up. Friends started to join in. When Weymar shared the work on social media, that's when things really took off and the Tiny Pricks Project was born.

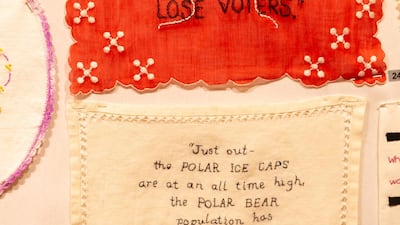

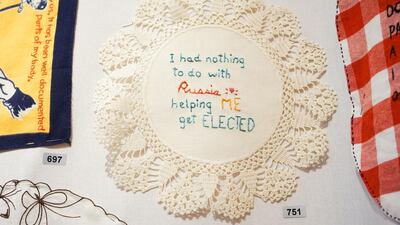

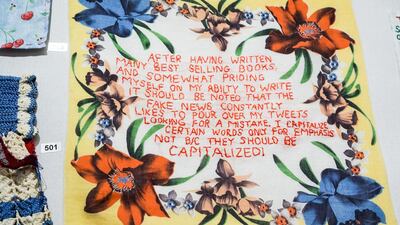

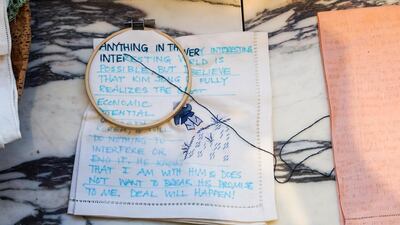

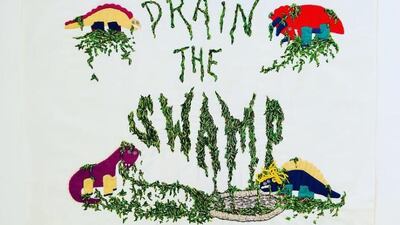

Weymar refers to the initiative as "a material history of Trump's quotes", and it has become a form of artistic resistance against the US president's policies and online statements. The idea is simple: take a tweet or statement by Trump that has affected you and stitch it. No aesthetic guidelines to follow. No level of expertise required. For the artist, this adds to the appeal. "It's not as much pressure as if I said to you, 'Stitch a piece about a memory that's important to you or a political event or translate a photograph in your childhood.' All of that would be much harder than just a quote and because the quote is there." The project's title comes from the fact that Weymar considers every tweet or quote a tiny sting or stab, though it is also a reference to needlework.

People around the US began submitting their pieces or pictures of them to Weymar's studio, which would then be shared on the project's dedicated Instagram page. To help it gain even more momentum, her social media-savvy teenage daughters came up with a campaign centred on a shared goal: gather 2,020 pieces by 2020 (#2020by2020) – just in time for election year and "a constant reminder that we have opportunity for change", says Weymar.

Back in the spring, the artist and mother of four felt like they had set an "impossible" aim, but the project now has more than 1,800 pieces in its inventory, and more arrive every week. Online, its following keeps growing – the Tiny Pricks Project Instagram account has more than 40,000 followers. "Honestly, if there can be 500 pieces, there can be 5,000, and if there can be 5,000, there could be 50,000," Weymar says, adding that "the more pieces there are, the more it's about a group and less about the individual". It also makes a stronger political statement. Having a sizeable body of works has also helped the project build a large enough collection to put together an exhibition. So far, there have been three, with previous shows in New York and San Francisco, and a current show in Speedwell Projects in Portland, Maine, which runs until November.

In an exhibition space, the works grouped together offer a more concrete view of Trump’s ideas. Tweets come and go. The constant churn of offensive comments on the news cycle can make them hard to track. But a wall of embroidery pieces that spell out one quote after another creates a visceral effect. Here, there is an immediacy to language when it is not mediated through screens. “It’s a medium that I relate to and also it’s a way to relate to other people through something you don’t usually see stitched. You usually see something shared or retweeted,” says Weymar.

A piece of embroidery is perhaps the exact opposite of a tweet. While a 280-character stream-of-consciousness rant can be fired off in seconds, needlework requires you to complete words one stitch at a time. This conscientious effort is not lost on Weymar. "It's a gift of your time," she says. "It's a gift of your creative energy. And it's a gift of your political opinion."

Looking at the works posted on Instagram, we can see how Trump's quotes have affected participants deeply, and how the act of embroidery empowers them to speak out. A recent submission by artist Maria Wulf is from a tweet Trump posted after the UN Climate Summit, where teenage activist Greta Thunberg made a moving statement about the world's fate in front of world leaders. With mocking undertones, Trump described Thunberg as "A very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future."

The stories behind the works get even more personal. Using a Raggedy Ann Doll made by her mother in the 1960s, Jenny Morgan stitched the words "Sadly, she's no longer a 10", which Trump said in reference to model Heidi Klum in a 2015 interview. For Morgan, the doll "represents a mother's love, wisdom, and empathy. True beauty". Trump has been criticised for the way he talks about women and degrades their character based on appearances. When asked about rape accusations made by writer E Jean Carroll in June, for example, Trump told political news outlet The Hill: "I'll say it with great respect: Number one, she's not my type. Number two, it never happened. It never happened, OK?"

“She’s not my type” is one of the most common phrases stitched and submitted to the project.

The works are not just a way to speak out against the presidency. They also confront larger global issues. Janet Burroway's son, Tim Eysselinck, was a soldier and mine removal expert during the Iraq War in 2003. In her artist statement, she writes, "He got enough of war, and came back bitterly disillusioned with the Army, the occupation, the privatisation of which he was an unwitting part, and George W Bush. He took his own life two months into his 40th year."

![“[I] am very happy to offer [this piece] to the Tiny Pricks Project, which seems to me the right place to speak out against war," says Janet Burroway. Her son was a soldier who served in the 2003 Iraq War and took his own life after coming back to the US. Burroway has used his old baby clothes to create the piece for the project. Courtesy Tiny Pricks Project](https://www.thenationalnews.com/resizer/v2/CAIM45TNZJYRR4MPDYVVCXE3DE.jpg?smart=true&auth=fec5525d0d61d291b4280615ad87992a2b9a80498d395a452183d2e3c7e30eee&width=400&height=400)

Taking one of her son's baby clothes, Burroway stitched the words: "He knows less than I do about Russia, and I know nothing," which Trump said about Mitch McConnell in the midst investigations about the government's ties to Russia. She explains: "I am very happy to offer [this piece] to the Tiny Pricks Project, which seems to me the right place to speak out against war."

As the initiative nears its goal, Weymar has started a UK version after receiving many requests to do so. This time, the target is UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, seen as a kind parallel to Trump, as he navigates the complex waters of Brexit. "As soon as I get the Tiny Pricks planned out for 2020, I hope to find a partner in the UK and work on that project," she says.

For now, Weymar wants to focus on presenting more exhibitions, especially if it means creating dialogue with those who might not agree with the project or its ideas. “The goal is to exhibit it in swing states for 2020,” she says, acknowledging that previous exhibitions have been located in more liberal states.

“What if it were somewhere where you were challenged? What if you walked in and it challenged what you thought and believed. Would it be a kinder, gentler, a different way of being challenged?”

![“[I] am very happy to offer [this piece] to the Tiny Pricks Project, which seems to me the right place to speak out against war," says Janet Burroway. Her son was a soldier who served in the 2003 Iraq War and took his own life after coming back to the US. Burroway has used his old baby clothes to create the piece for the project. Courtesy Tiny Pricks Project](https://www.thenationalnews.com/resizer/v2/CAIM45TNZJYRR4MPDYVVCXE3DE.jpg?smart=true&auth=fec5525d0d61d291b4280615ad87992a2b9a80498d395a452183d2e3c7e30eee&width=400&height=225)