Showcasing 17 international artists, the Known Unknowns group exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery in London offers a fascinating insight into assembling a major collection and the diversity and ever-evolving careers of its featured artists.

Riffing off the famous soundbite from then United States defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld in 2002 about the Iraq War which was subsequently a title of a book by the gallery’s owner, Charles Saatchi, the exhibition features artists who are largely unknown in the mainstream art world, but are greatly admired by their contemporaries and seen as breaking new ground.

Each of the 17 – who span more than a generation from their births between 1966 and 1990 – is given generous space in the 70,000-square-foot space in Chelsea, to underline just why they deserve greater recognition.

The presentation raises questions of identity, cultural boundaries and social divisions, with contemporary subjects and perspectives experienced via a rich and varied display including painting, sculpture, video and multimedia.

Predominantly working in collage, the Danish artist Kirstine Roepstorff incorporates media images into her work that visualise existing power relations and critically deal with the history and failures of political ideas.

Guided by the theme of darkness, Roepstorff appreciates that embracing shadows is essential to her working process. She says: “It’s one of the essential themes and resonances in my life. We discover our potential and opportunities by shedding light on our shadows – as individuals, as a generation, and as a society.” She is concerned with exploring the cracks, breaks and spaces in-between.

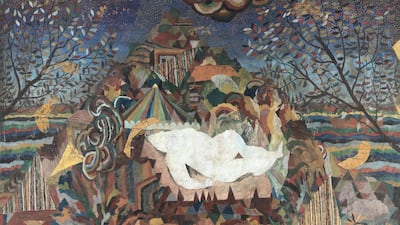

In Hidden Truth (2002), Roepstorff depicts an interpretation of natural landscape formations with an explosion of images at the top of the canvas, which hovers above a picturesque landscape below. Roepstorff has fabricated this place, with planets, buildings and fish being thrown out like a big bang.

On seeing her work in the flesh, one is taken aback by the sheer scale of her artwork, in which her use of collage gives the images additional depth as they move away from being 2D artworks and take on a sculptural quality. “Collage is my first media, and from this arose something which could look like painting, but it’s not really painting, it’s more like residue,” she says.

Roepstorff is driven by the power of aesthetics and visual culture. She says: “I use aesthetics, with all it encompasses of incorporeal sensibility and bodily determination, as a handle that allows me to open doors leading to the subtler and more intangible aspects of everything that moves us – physically as well as mentally. I would say that the starting point of our being is aesthetic. We are creatures governed by senses first of all.”

She has also moved away from western philosophies that hinge upon scientific logic and invests instead in the sense of balance with the body that is taught by eastern traditions, which comes across through the balance between figuration and abstraction in her artwork.

Focusing on journeying, foreign places and the stories that can be told through objects, the Berlin-based British artist Tom Anholt alludes to art historical traditions to open up broader themes of time and object-making.

In his painting, The Lion's Second Dream (2017), he has taken a small ivory sculpture of a man with a lion's head, between 35,000 to 40,000 years old, as inspiration to meditate upon the passage of time and artistic processes of making.

Anholt says: “Roughly 40,000 years apart, the maker of the Lion Man and I have, for different reasons, done a pretty similar thing. I find that an overwhelmingly beautiful thought.”

A man or perhaps a giant lies in the centre of the work on a mountain with a lion asleep below him, perhaps dreaming of the nature around him. Camouflaged in the background is the top of a carousel, perhaps a whimsical nod to the circus and the dreamlike world of the magic roundabout.

The textures and various coloured patterns across the piece are not unlike early Cubist paintings, such as landscapes by Cezanne, where the landscape has been broken down into blocks and reconstructed once more. His process of abstracting the landscape adds depth as a tree sits halfway up the mountain above the white figure. This painting shows the whole journey before us as Anholt explores this story.

Anholt’s rich Irish and Persian-Jewish lineage provides a source of inspiration, pushing him to explore Christian and Islamic art history. He says: “I like this idea that everyone carries their ancestry within them; stories of our family histories. Painting is a process that unearths them and turns them into pictorial language.”

His method of storytelling is not linear and moves unpredictably between art historical references from Hellenic antiquity and Persian miniature painting to European Romanticism and beyond.

He says: “More recently, I think of the narrative less as clear stories and more as poems or songs. They give a feeling and suggestion of narrative – I believe the viewer should be able to find their own stories in the paintings. I want them to be open, so that they lead the emotion without there being a right answer.”

As with Anholt’s work, the Dutch London-based artist Saskia Olde Wolbers uses storytelling as the glue between thought and image whilst exploring the relationship between digital and analogue imagery.

In her video installation, Interloper (2003), the narrative voice guides you across images that change between representation and abstraction. She blends fiction with reality, taking inspiration from pseudolica phantastica syndrome, a condition where the sufferer makes up most of his life out of lies that become indistinguishable from the truth. The narrative is told from a doctor's divided point of view; as a phantom lover and a placebo surgeon.

Olde Wolbers explains she chose this character because, “being a doctor is a very suitable job to pretend to have. It is a noble profession with a status and a clear uniform and one could blend in nicely walking around in the endless labyrinth of hospital corridors. The hospital also becomes a metaphor for a space in the character’s head.’

Although referencing computer-generated imagery, the liquid visuals in Interloper are entirely analogue, shot in real-time inside model sets. She says: "The process of image making is an experimental, completely analogue process, where temporary and unstable miniature film sets are dipped in paint and filmed, in real time, underwater.'

____________________

Read more:

Safeya Binzagr: the woman who put Saudi art on the map

Rare opportunity to see work by New York sculptor Jene Highstein

Emirati art collector sues auction house Sotheby's over Dh3.6 million Egyptian statue sale

____________________

Skeletal objects, architecture and living forms are given a “skin” when dipped in paint and submerged underwater giving them an otherworldly quality. The materials are animated through this unpredictable confrontation of oil and water and oscillate between representation and abstraction.

These recordings of sculptural and chemical lo-fi processes subvert the truth-telling qualities of filming reality whilst the absurd voiceover narration reminds viewers that they do not know whether what they are seeing is fact or fiction, revealing how biography and the documentary are subject to translation and interpretation in the same way as fictive genres of storytelling.

Another artist who explores the familiar and the strange is Isobel Smith, who propels the two concepts together, attempting to have both present at the same time. Her practice seamlessly moves between sculpture, performance and moving image as a way of not restricting her process.

Bunny (Crying the Neck) (2017), featured in the exhibition, is one of these sculptural outcomes of her performances, as many of the original materials in the performances are destroyed in the process of making a permanent piece. She says: "The performance is fleeting and ephemeral – but the image of it may burn more powerfully and more permanently into the viewers psyche than a perfectly presented sculpture.'

Smith seeks to remove herself physically from the work, but only as a way of creating another dimension for her performances where she can move into the sculptures – sometimes puppets – and create living and breathing artwork. On the impact of using puppetry in her performances, she says: “I brought this experience to my performance practice, now attempting to climb inside the puppet, breathe with it and look out of its eyes, and backwards and inwards – discovering a strange perspective – looking out of an art object.”

The exhibition ensures the Known Unknowns are rightly known, bringing these artists to the attention of a wider audience, and collectively offering a glimpse at the breadth and diversity across global art practice in today’s modern digital age.

Known Unknowns runs until June 24 at the Saatchi Gallery, London. For more information visit www.saatchigallery.com/artists/known_unknowns/