At 70, Rose Issa claims she’s “semi-retired” but her energy and commitment to Middle Eastern art are as strong as ever. The well-known London-based curator, writer and producer recently went on a mini-tour of Washington DC, taking in My Iran: Six Women Photographers, a show at the Freer Gallery of Art running until February, which features five of Issa’s close collaborators. While there, she also spoke at the opening of the inaugural exhibition of the Middle East Institute Art Gallery.

The MEI show is the latest incarnation of Issa’s Arabicity, a term Issa coined for a moving and varying series of exhibitions she has curated over the past 11 years in Brussels, Liverpool, London and Beirut, showcasing what she believes is the finest new art from the Arab world.

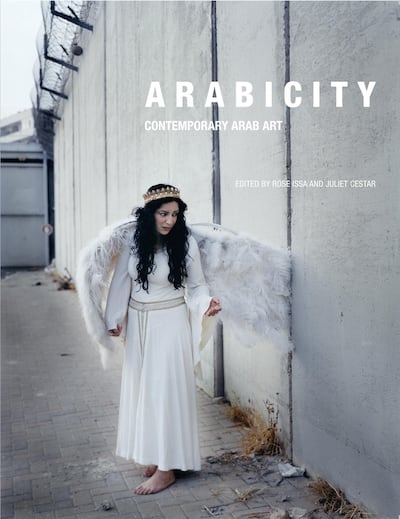

Arabicity is also the title of a new book, being published this month by Saqi Books, reflecting Issa's vast achievement in fostering Middle Eastern artists. It features more than 200 illustrations from 50 living Arab artists.

Amid all this, Issa still found time to catch up with The National, taking a break from her recent holiday in Nice to discuss and compare the merits of work from the Middle East versus Europe. With restless enthusiasm, she begins by explaining the superior vitality and relevance she finds in art from Arabia. "The Western concerns are not the same as ours, whether aesthetical, conceptual or artistic," she said. "In Europe, apart from Banksy, I see people copying what those like Marcel Duchamp did 100 years ago."

Duchamp, an American-French painter who died in 1968, was seen alongside Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse as driving Western modernism. He believed art should address the mind as well as appeal aesthetically, but Issa argues Western art no longer engages with current social realities because it hasn’t moved with the times.

“Damien Hirst for me is Marcel Duchamp 100 years later,” she says. “This doesn’t bring anything new, it doesn’t speak, while the work of [Abdul Rahman] Katanani or Mona Hatoum reflect the concerns of the general public in our part of the world.”

The work of Palestinian artists Katanani and Hatoum are both found in Arabicity. "Katanani is in his early forties and lives in the Sabra-Shatilla camp in Beirut," Issa explains. "When you go to his studio, it's in a [former] hospital destroyed by the Israelis in 1982. It became flats for refugees with almost no doors. He produces work with the elements immediately available for him – corrugated metalwork and barbed wire."

Issa herself moved to Lebanon aged 12, following an early childhood spent in Tehran with her Iranian mother and Lebanese father. After studying mathematics and statistics at the American University of Beirut, she left the city, along with many other Lebanese citizens, during the civil war. She then went on to do a Masters in Arab literature and international relations at the New Sorbonne University in Paris.

In France, Issa successfully organised a film festival on the theme ‘Occupation and Resistance’: “I called film director friends in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. The cinema asked for 10,000 francs. I went to the Libyan embassy [which was funding the project], they handed over the cash, which I took in a taxi to the cinema.”

This was the moment that cemented Issa’s career as a curator and advisor for film festivals, a trajectory that would take in Cannes, Rotterdam, London’s Barbican and many others in later years. Back then, she also noticed there was little awareness of modern Arab art in 1980s Europe. “The ethnographic museums – the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum – showed some interest. My argument, though, was that our culture didn’t stop 200 years ago, we were still producing art.”

Issa began curating art after an offer from Iraqi architect Mohammad Makiya. “He had space in a building in London, opened it as the Kufa Gallery [in 1985] and paid me a salary. After two years, I went freelance, although from time to time I did an exhibition with them.”

Issa then went in search of wider exposure. She worked at the Leighton House Museum, the V&A, St Petersburg’s Hermitage, Tate Britain and Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum. She encouraged Venetia Porter, assistant keeper at the British Museum, to collect modern Middle Eastern art. In 2005 she opened Rose Issa Projects, which ever since has hosted exhibitions promoting art from this region and published art books on topics ranging from photography to calligraphy.

Issa says her approach to curating is simple: “I trust myself. If something is new, exciting, I’m interested. And if I’m interested, I want to share it with friends and other people.”

Arabicity, edited by Issa with art historian Juliet Cestar, rounds up material from Issa's shows since 2008 that have focused on the theme of "Ourouba". "[The word] ourouba is not translatable so I translated it as 'Arabicity'," she says. "It's whatever has to do with the word 'Arab' – ayn, r, b, the root. The shows' catalogues went out of print in a few weeks, so I decided to do a book with Saqi, in paperback, so students can afford it, and where I can put more than [is in] the exhibitions."

The book charts the path of modern Arab history. As Issa writes in her introduction: “We start with artists from Palestine, one of the first historical issues to augur the dismantling of the Middle East; then comes Egypt, which was at the heart of Pan-Arabism…” Then it’s Lebanon, where “decades of civil war and invasions produced a whole generation of young artists who remember only conflict”. Next are Iraq and Syria, then north Africa, where “many artists have had a foot in Europe”, and finally Gulf artists “who capture different inner tensions resulting from stagnation versus growth”.

The works Issa has chosen are both vivid in their aesthetic and provocative, even disturbing. The composite tableaux of Morroco's Hassan Hajjaj blend images with patterned textiles and empty cans of popular food. The cover image, Angel, is by Jerusalem-based Palestinian Raeda Saadeh, whose work often sets her own body in some guise, or disguise, against a backdrop of occupation.

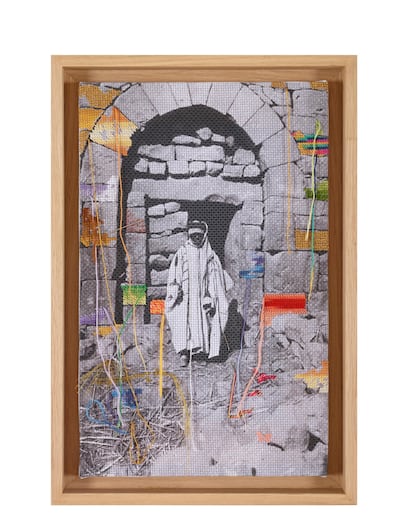

Saadeh's Crossroads, a self-portrait by an open door with a suitcase next to one foot and a concrete block encasing the other, features in a chapter Issa has written on modern Middle Eastern art in another new book called The Image Debate: Figural Representation in Islam and Across the World, edited by art historian Christiane Gruber and published by Gingko. It is a tome of 13 essays and around 200 illustrations, including Iranian artist Farhad Ahrarnia's Ballet Pars no 1, an installation with digital photography of ballet dancers mixed with hand stitching. Issa has been so taken by his style that she has also curated Art in Another Language, an exhibition of Ahrarnia's latest work that opened at Beirut's Galerie Janine Rubeiz on Thursday, September 19.

"Farhad lives between Shiraz and Sheffield, where he went aged 18 to study," says Issa. "These are two cities where textiles and silver are both important, and this shows in his work." Issa was first drawn to Ahrarnia by his video Mr Singer, which is based on the character Sergeant Zinger – from Simin Danishvar's 1969 novel Savushun – who sold Singer sewing machines while working as a British spy.

“Farhad’s work was very original, a video of a sewing-machine mapping the Middle East, and I was the first one who bought it,” says Issa. “In 20 years’ time, he will stand out as one of the finest artists.” Given the number of trail-blazers who have emerged over three decades from under Issa's wings, this is praise indeed.

For more information, visit www.roseissa.com