More than a decade ago, I worked at Cisco Systems and travelled to Africa a lot. Mesmerised by the continent and largely inspired by my father, I explored the art scenes of the many cities in my free time. How could this art not exist beyond African borders? Why couldn't I find any African names in European exhibitions? How could there be such a big gap of information on African artists? I realised how important my father's visibility in Europe was to his career – he had made a name for himself in Paris, then returned to Morocco.

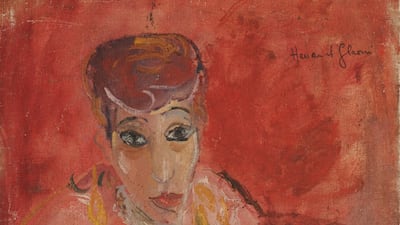

The idea to do something for African artists who were not part of the global discussion started to crystallise. So, I quit my job in 2011. Though I had considered an art fair as a voice for African artists, a lot of uncertainty clouded my life. At the time, I was co-curating a show, Meetings in Marrakech: the paintings of Hassan El Glaoui and Winston Churchill, which opened at Leighton House Museum in London in January 2012. By then, my father had developed dementia and I didn't know if I should or could share my uncertainties with him. "You don't look at ease," he said to me suddenly. "I know you are organised, and that there is a lot of chaos in your head, but just accept it, and you will be fine. It's normal to feel like this; you are doing something that has never been done."

It was so poignant. Had I known that would be his last piece of advice to me, I would have taped it. I felt relieved. The buzz around the exhibition inspired and energised me, and in 2013, I launched the first 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London.

The anecdote in our family was that my father learnt to paint because of Churchill, who, on a visit to Marrakesh in 1943, met and befriended my grandfather, Thami El Glaoui, the tribal warrior of the Atlas Mountains and last Pasha of Marrakesh. They became good friends. My father painted; my grandfather disapproved. It was akin to a dishonour for the prominent 300-year-old Glaoua Berber tribe for the heir to opt for painting in place of his birthright. But Churchill saw talent in my father's work and encouraged my grandfather to send him to France to study art seriously. And so, in the early 1950s, my father enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he trained under French avant-garde artist Emilie Charmy, whose figurative and landscape paintings hung in our home in Rabat.

Many of my father's paintings in the Meetings in Marrakech exhibition featured horses, and I once asked him why he was so fascinated with the creatures. As a young man, he had received money from his father and bought a horse that became his infatuation and caused him to neglect his studies. The school raised a red flag, and my grandfather gave the horse to another tribe that practised fantasia, a form of martial arts performed during cultural events in the Maghreb. It didn't stop my father from going to see his horse perform. The animal appeared prominently in his work while in France – a response to a deep nostalgia for his homeland.

Painting was a soothing experience for my father. He never talked about difficult moments in his life, such as when his family's wealth was confiscated following the death of my grandfather in 1956 after Morocco's independence, or when my father and his brothers were kidnapped in 1957 for almost two years. Those experiences no doubt made an impact on him, and he often said his passion for painting helped heal some wounds.

He was so calm and collected. I remember him having breakfast on the terrace of our house in Rabat, in a different spot every day to gaze at the flowers, and the pomegranate, orange, lemon and avocado trees that he had planted. He was aesthetically motivated, and food had to look beautiful, too. We didn't have a father who woke up and went to work and it had always been funny to explain to people, because we didn't have the same familial structure. Though he worked for the king as an attache, he was first and foremost an artist and that, among other things, meant we went to his exhibitions and other shows. Yet some at school had never been to museums, so how do you explain that that's a lot of what we did?

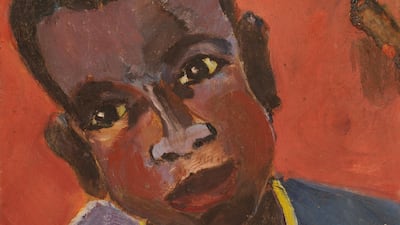

Four daughters in the house made for a boisterous, fun place. Our father's studio was in the heart of our home, where I loved to hide between the many easels. He only painted portraits of his family and would ask us to pose for him if we were nicely dressed, which is awful when you're a child. We'd sit there for about 30 minutes and only a few lines would appear on the canvas. It looked like he was staring, but he wasn't and sometimes he closed one eye. I felt like he was disconnected, almost possessed. He could stay in that moment for hours, almost like he was meditating.

I knew I didn't have a lot of time with my father, especially since I am the youngest. My friends' parents were in their thirties, my father was in his fifties and 20 years older than my mother. I had nightmares he'd die because he was older.

He was the kind who couldn't resist sketching something on a napkin or tablecloth, wherever and whenever. It was sad to see that spontaneity leave him. He would have a go at old paintings, a line here, a dash there, but towards the end, he would say he had produced enough. When I saw him slow down, I started archiving his work.

Two of my nephews and I are working on his catalogue raisonne as part of our commitment to his legacy. We want his work to be more visible in the Middle East. In his later life, he wrote a lot – in bad handwriting – and one of my projects is to try and decipher these notes to better understand him.

By 2013, when his dementia had progressed, he wasn't very talkative. I still had plenty of questions for him; I never asked him about God, his childhood, his favourite colour. I'm hoping that the more I work on his life as an artist, the more answers I'll get.

Remembering the Artist is our monthly series that features artists from the region