A funeral service gives relatives and friends a chance to say their last goodbyes to the dead, to grieve and mourn. However, what happens when there is no body to bury? Iraqi artist Ali Eyal, whose father and five uncles disappeared in 2006 during sectarian violence in Iraq, says he has become like a walking graveyard.

"If you lose someone and can't get a chance to bury them, his or her grave will be in your mind," he tells The National.

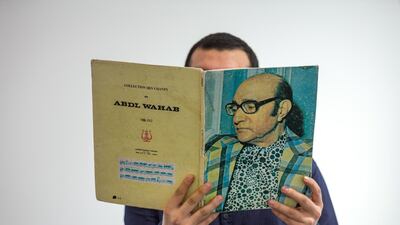

The artist, 26, has not had a picture of his face taken since 2012 in tribute to his father and uncles. "It's my way of showing that I'm missing as well."

However, Eyal tried to say goodbye to his father in a 2017 film titled Tonight's Programme, which debuted at last year's Sharjah Film Platform. Set in Baghdad's Khuld Hall, the film merges Duke Ellington's 1963 performance with the violent coup Saddam Hussein carried out in the same theatre 16 years later. It creates a fictional space dedicated to all those who disappeared in Iraq, giving Eyal a chance to communicate with his father.

"I've always been interested in the merger between personal history, transitory memories and fiction," he says. "The central themes of my work are always questions posed by my reality, questions like how to deal with catastrophic events, the limitations of which I try to overcome with fiction and artistic narrative."

One of Eyal's more recent works is on display at Warehouse421 in Abu Dhabi, but this time it explores the boundaries between formal and independent publishing. The work, which is part of the exhibition How to Maneuver: Shape-shifting Texts and Other Publishing Tactics, was the result of an old blue suitcase he stumbled upon in his family's home in Baghdad.

"In the suitcase were old magazine clippings and photographs, all of which had my mum's notes scribbled on them, stuff like Nizar Qabbani poems and questions addressed to her friends."

The work, titled No Part Of This Book May Be Reproduced, In Any Way, By Photocopying, Recording, Or Otherwise, Except with the Prior Consent of the Publisher, exhibits his mother's belongings. Pages of musical compositions, old magazine covers and photographs are pinned on the wall, with his mother's notes written in pencil. Some refer to the US invasion of Iraq, others are about a birthday party she was planning for her daughter.

Eyal's illustrations – some of human figures and dolls, others of beds and fans – are drawn over them. The drawings flow out of the pages, connecting the disparate sheets in rippling blue ink.

"My mother documented everything from 1991 until the mid-2000s," he says. "She stopped because of the country's circumstances, as well as some personal reasons. I placed some government papers at the very end. I consider them the reason why mother stopped writing her notes."

Eyal says he played with the different pages like elements on a storyboard. To him, the sheets comprise different chapters of a book and the suitcase itself was a publishing house. The work was exhibited in Beirut Art Centre before coming to Abu Dhabi.

"To me, the suitcase's contents are like a book that never got published," he says. "The drawings are like blue ink that has spilled in the suitcase and covered the pages as it travelled around Iraq, then to Beirut and Abu Dhabi."

In 2016, Eyal was selected as one of the artists for a year-long residency at Ashkal Alwan in Beirut. That year turned into three. His artistic practice flourished and he began using a wide range of media in his works. Though his pieces primarily incorporate multimedia drawings, he often uses photographs, text and installations. "I was given a studio at Ashkal Alwan. The manager, Christine Tohme, was very generous," he says. "I was very lucky. There's not much of an art scene in Baghdad. Our politicians are too busy with the military."

Eyal is now bound for the Netherlands. He says he has been given a studio there for two years, at the end of which he will exhibit new work in an open studio. "For now, I want to spend time with my family in Baghdad and my friends in Tahrir," he says. "It's very important to me."

Tahrir Square is at the centre of the protests in Iraq, which began in October, as people rallied against corruption and foreign interference in Iraqi affairs. The demonstrations are a sensitive subject for Eyal, who says

it is not the time for art. "People aren't protesting for jobs or government services," he says. "This is a movement to take back the country and restore people's rights.

Maybe in five, six years, after it all sinks in, maybe then I'll do a piece of work on the revolution."

How to Maneuver: Shape-shifting Texts and Other Publishing Tactics is on show until Sunday, February 16