This month a unique exhibition opens at the Barbican, Europe's largest multi-arts venue, nestled amid the concrete jungle of the City of London. With its odd amphitheatres and jagged high-rises, elevated gardens and glittering windows, it's an appropriate setting for The Surreal House, an exhibition-cum-installation that juxtaposes classic surrealist works with those of newer artists in an innovative and enveloping experience.

"The house has always been a rich area for artists, and a laboratory for architects," says Jane Alison, the curator. "We wanted to plunder the realm of the alternate or 'other' house, which is of course a loaded area for memory, anxiety, play and domesticity. We also felt that surrealist architecture hadn't really been covered in an exhibition like this before". But this is far from being an exhibition of architecture - the first name that comes to mind, Gaudi, is represented only second-hand through a pair of Man Ray prints. This is the house as a collection of interiors, and as expression of introversion. The exhibition is housed in a site-specific network of rooms, roofs and walkways designed by the architects Carmody Groarke, that fill the two-storey exhibition space with light and dark, openness and enclosure, compression and expansion. When the first room is basically a shrine to Sigmund Freud, you know something unusual is afoot.

The exhibition is supported by the Freud Museum, a townhouse just off London's Finchley Road that houses the doctor's memorabilia, including his legendary consulting room. One of the exhibits here is his leather desk-chair which, displayed behind glass against a background of deepest black, looks shockingly human. Its scarred head, back and arms are like a totem, a voodoo doll or one of the tribal fetishes that Freud loved collecting. Displaying what is essentially memorabilia as art is also in itself a nod to Marcel Duchamp.

The room is dominated by the artist Rachel Whiteread's modern sculpture Black Bath. Against the sensory-starved black backdrop, the concavity left by a rubber-cast moulding of a bathtub suddenly looks like a sarcophagus. It is a reminder of death, sinking, of the submerged subconscious. Over it all gazes a photograph of the spy-hole on Freud's consulting room door. This is what the exhibition does so well. It is a dark labyrinth where the context is as important as the content.

The usual suspects are all here - Dali, Man Ray, Duchamp, Andre Breton - but they're not the stars of the show. Dali's famous Sleep sits peacefully at the top of the stairs. "The real idea was to explore what a surreal space could be," says Alison of the relationship between works and rooms. "We are bringing together paintings which depict the house, films which perform the house, and architecture which designs and builds the house." There are individual treasures to be found at every turn, often emerging slowly from the surrounding strangeness. A seemingly chaotic little heap of scrap metal on the floor turns out to be casting a shadow of two rodents against the wall.

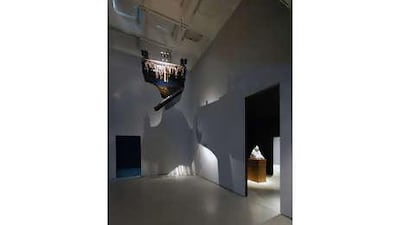

A tiny house made of diaphanous tissue held together with a single pin turns out to have been made by a dying artist from his own surgically-removed skin, reminding us that our first home - the structure that most shelters and sustains us - is our own body. Surrealism at the Barbican is not silly, zany, wacky art. The juxtaposition of pieces here tends toward philosophy and psychological comment rather than humorous theatrics. Not that drama is lacking. The weird soundscapes and blacker-than-black settings give The Surreal House an atmosphere unlike most exhibitions you'll see. Wandering away from the Freudian shrine, viewers enter a seemingly empty room. Yet above them, suspended upside-down from the ceiling, is a grand piano - Rebecca Horn's Concert for Anarchy (1990). Suddenly it creaks, clatters, and jolts towards you, the lid flying open and the keys bursting out of the casing like teeth from a busted mouth.

Not everything in the exhibition is Surrealist with a capital S. It combines the unexpected, the ponderous, the playful and the practical. Architecture and design are not wholly absent, with the postmodern master Rem Koolhaas' Villa Dall'Ava and an unexpectedly carefree Le Corbusier represented by his Beistegui Apartment, the roof garden of which comes on like a De Chirico painting with its whitewashed walls deliberately obscuring the Parisian panorama, and an outdoor fireplace providing a cheeky visual echo of the Arc de Triomphe.

The Surreal House ranges so widely with its theme that it sometimes requires us to work backwards to the idea of home from a Man Ray photograph of a giant egg, or Jan Svankmayer's blissfully inventive 1971 film Jabberwocky, which has little to do with the poem and much to do with childhood, fantasy and the innocence and darkness of the nursery. But these excursions from the straight and narrow are at once necessary and welcome. Svankmayer's film is a highlight - made in Czechoslovakia using naturalistic stop-motion techniques, the 14-minute caper stars a marauding wardrobe and a flying sailor suit, families of creepy cannibal dolls and an irrepressible blob of ink. Political undertones abound, but the net result is a film that has a roomful of grown men in fits of giggles.

Having traversed The Surreal House, climbed its stairs and looked down on the other visitors, gaining a second remove from the works on show, the viewer escapes with regret into the concrete city outside it. But the knowledge that each window hides bizarre interiors, dark secrets and endless possibilities, leaves it richer as a result.