"In many ways, I am probably making the same film over and over again," says artist Amar Kanwar, whose thoughtful, eye-opening movies and multimedia installations have earned him numerous awards throughout his 30-year career.

His works are being presented in two concurrent exhibitions in the UAE – Such a Morning at the Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai and The Sovereign Forest at NYUAD Art Gallery in Abu Dhabi, which both run until May. "I feel like there's a central thread that runs through all my work," he says. "And the thread has to do with multiple forms of violence – be it human violence, ecological, interpersonal, be it among communities, nations, religions."

Yet Kanwar's films, which he directs and writes, contain little violent imagery. Instead, they are filled with scenes of natural landscapes and poetic, philosophical texts that often replace dialogue. Within these narratives, the filmmaker and his characters confront violence in meditative, moving ways. Born in New Delhi in 1964, Kanwar studied history at the University of Delhi, where he cites specific events in 1984 that spurred him towards social activism. These were the assassination of former Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards, and the subsequent massacre of almost 3,000 Sikhs as a form of retaliation. Then a month later came the Bhopal disaster, where a gas leak at a pesticide plant exposed half a million people to toxic substances.

"They impacted a lot of young people who felt there was a need for accountability … At a certain point, I felt it was important for me to find a way to respond," he recalls. He went on to study film, and began working independently for a few years. But he soon grew weary of the profession, and its costly nature made it difficult to produce work, too.

He became a researcher at India’s People’s Science Institute, where he travelled around the country and the subcontinent, learning about occupational health and the mining industry. Interestingly enough, his time there brought him back to film. “It ended up with me having a lot to say,” he says.

The breadth of his subjects prove this, from his film trilogy on the history of Partition, along with its devastating effects on India and Pakistan, and The Lightning Testimonies (2007) a multichannel installation that traces sexual violence against women from the time of Partition to the present. His complex exhibition The Sovereign Forest, an ongoing project comprised of films, images and mixed media installations, expands on these concerns for social justice, specifically about the rights of residents in the Indian state of Odisha (formerly Orissa), whose lands are threatened by extractive industries.

Abundant in natural resources, such as coal, bauxite and iron ore, the state has attracted investments from companies overseas. This has resulted in the forced displacement of residents and clashes, as resistance groups seek to protect their properties against investors and even the government entities that support them. This gets to the heart of what The Sovereign Forest is about. Throughout the show, Kanwar presents us with ways of thinking about land ownership and justice – how do we define people's rights to land? Is it through official title deeds, which can easily be destroyed, or indigenous histories and cultures, which are passed on through generations?

As the work has evolved over time, it has been displayed in various ways. For its iteration in Abu Dhabi, The Sovereign Forest spreads across five rooms. The exhibition begins with the film The Scene of Crime (2011), which details natural landscapes on the brink of disappearing, as corporations and governments attempt to convert them into industrial sites.

In the next room are three large books, The Counting Sisters, The Constitution and The Prediction, made in collaboration with graphic designer and filmmaker Sherna Dastur, who has hand-sewn pages made from banana and cotton fibres to create these beautifully textured works. The left-hand pages of each book contain text, while small films are projected on the other side.

In a small room adjacent to these displays is a grid of seed boxes on the wall. Totalling 260 varieties, these seeds have been developed by residents in Odisha over generations, with locals recognising each type according to flavour and adaptability to the soil. This type of knowledge, often unwritten, remains of little value in the face of corporate money. Kanwar brings to light the differences in the relationship between local inhabitants and investors to the land. The former seek to cultivate it, while the latter simply wish to exploit it.

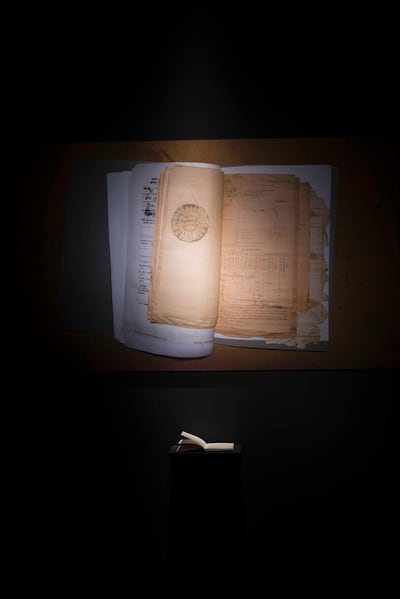

Between 2012 to 2016, The Sovereign Forest was installed at the Samadrusti campus in Bhubaneswar. During this time, Kanwar invited visitors to help build an archive of evidence that could document villagers' struggle against mining companies. The result is one of the exhibition's highlights – a collection of images, newspaper clippings, land records and maps that chronicle the various histories of resistance within Odisha.

A section on Jagatsinghpur details a specific instance where residents seized a hard-won victory over Posco, a South Korean company that wanted to build a steel plant and port in the area. Signing a deal with the local government in 2005, Posco sought to take over 1,250 hectares of land for their project. Villagers protested and clashes ensued. The battle would rage on for more than a decade, until the company backed out of the deal in 2016. A small book called Time is a record of weekly, sometimes daily, developments within the village, noting down the sit-ins, protests, discussions and petitions made by local resistance groups.

Throughout his work, Kanwar imagines the possibilities of “poetry as evidence”, a concept he introduced in 2008, which calls into question our current systems of justice and how they deal with issues of violence and trauma. “I began to feel that there was a way in which you could formally understand a crime, any kind of crime. The formal way of understanding is through the law, through evidence, through a criminal justice system. And in some way, I started to feel that this whole process was quite inadequate for many reasons,” he explains.

The book The Prediction, for example, recounts the assassination of Shankar Guha Niyogi, a labour activist who was killed by industrialists. The case was put to trial, and though the suspects were convicted, the Supreme Court of India eventually overturned the ruling in 2005. For Kanwar, even in the face of so-called hard evidence, justice failed. Through this work, he weaves fiction and fact as an attempt to understand not only the loss of Niyogi, but to create a document that serves as a testament to his life.

"If we were to use poetry, which is inadmissible evidence, we could actually get an insight into the nature of the crime, the scale of the crime, its meaning and implications, from a totally different perspective," Kanwar says. Violence, he argues, cannot always be comprehended through facts or forensics. It requires a language that can encompass deeper ideas.

In Such a Morning at Ishara, the artist continues to reflect on themes of violence, but with a more philosophical approach. The film centres on a maths professor who inexplicably retreats from society to live in an abandoned train carriage in the forest. He arrives at the site with little baggage, building makeshift furniture as he settles in.

In the darkness, he has visions such as rain that falls in fiery sparks. He spends his days ruminating on good and evil, metaphysics, and simply trying to understand his own "darkness". By the end, he has an epiphany, and begins writing his thoughts down in letters to send to the people on the outside. Kanwar translates them into physical letters, working once again with Dastur to create paper pieces with printed text tacked to the wall. They are displayed side by side with small-scale film projections.

Each letter, which calls for several readings to fully appreciate, draws from various schools of thought, including Buddhist, Sufi and Hindu traditions. Kanwar does not settle for one certain philosophy – he acknowledges that he has never sought to be didactic. Instead, he asks us to explore these thoughts on darkness, truth, life and death in our own ways. "It's another way to discuss things that we normally don't do. So it's actually a proposition. It's an invitation," he says.

Does the work affect him? "If I'm trying to address a subject that has violence in it, I am not the one actually suffering. That pain is not necessarily on me," he says. "On the other hand … even if you were to get into the terrain of violence, you are not necessarily going to be shattered. You may actually find somebody who is responding to that situation with such grace, elegance, love and sometimes strength and generosity – and that gives you meaning."

Kanwar’s exhibitions are not only moving, but profoundly significant for our time. On one level, they operate as vital documentation of human struggle and dignity within the context of South Asia, but also for similar communities worldwide. Beyond that, they unsettle us – questioning the systems of law and authority that we’ve come to accept, asking us to confront our own struggle for meaning, particularly in the midst of violence.

It’s an experience that the artist goes through, too. Kanwar says, “Every time I make my work, I understand a little bit more about life, about how to live and how to die, for that matter.”

The Sovereign Forest is at NYUAD Art Gallery until Saturday, May 30 and Such a Morning is at Ishara Art Foundation until Wednesday, May 20