This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus, the extraordinarily influential movement that changed the built world around us: stripping away ornate cornicing and architectural flourishes, and replacing them with the clean lines and openness towards the outside that spoke of modern, egalitarian life.

The Bauhaus was conceived as a school in 1919. It did not distinguish between art, design, performance and architecture, and was housed in Weimar until Nazi opposition forced it to disband in 1933. Many of the lecturers fled to the US and western Europe. The founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, moved to Boston, where he became the dean of the Harvard architecture school. There he taught a generation of architects, while still designing buildings himself through The Architects' Collective (TAC), a collaborative firm of architects.

Other Bauhaus members, such as Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe, were responsible for some of the iconic buildings of the 20th century, such as the former Whitney Museum of American Art (now the Met: Breuer) in New York, and the Seagram Building in Chicago, respectively.

Building Bauhaus, the current show at the Jean-Paul Najar Foundation, brings the school’s influence closer to home: it looks at Bauhaus in the region, as well as in the design of the bespoke Alserkal Avenue space itself.

When Deborah Najar established the foundation in 2015, she commissioned one of Marcel Breuer’s associates, the Italian architect Mario Jossa – who also happened to be her father-in-law.

Jossa transformed the former warehouse space along clear modernist lines: the mezzanine bisects the ground floor at an angle, forming a triangular exhibition display area, while an internal window opens on to Najar's office upstairs.

Plans on view in the exhibition show that the original designs for the space were even bolder: the mezzanine was meant to have floated above the ground floor, and the staircase was to be open, floating upwards. (The designs had to be altered during construction, and the mezzanine is now supported by two pillars.)

Downstairs, Building Bauhaus provides an overview of the school's ethos and impact, particularly that of Breuer and the school's influence among post-war art, which is the focus of the foundation's collection.

But the biggest surprises are upstairs: the show's curator, Wafa Jadallah, has put together archival information on buildings in the Middle East where designs were influenced by the Bauhaus, uncovering a web of geopolitical ambitions, nation-building exercises, and regional stereotypes.

Rather than being a secondary territory for modernist architects, coming in line after European and American conditions, the Bauhaus intersected with notions of what it means to be Arab from the very beginning – and in unexpected ways.

"Modern architecture is known for its use of the cubic form, flat roofing, lack of ornamentation," Jadallah said. "But architecture in the Middle East before the 20th century already had a lot of cubic forms, flat roofing, and simple designs – that was part of traditional Arab architecture. When western modernist architecture came to the Middle East, while it was wonderfully innovative in Europe, people here were saying, okay, but we used to have this, too. Many of the decorative elements in architecture are western European transplants that the colonialists brought with them."

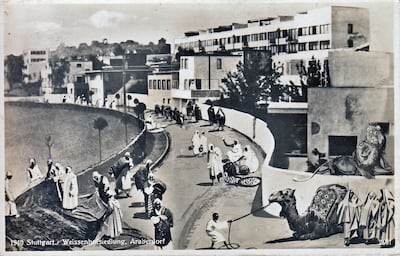

This connection was apparent at the time: when the Nazis closed down the Bauhaus in 1933, for example, they launched a publicity campaign against it by referring to it as “Arab architecture” – “as a negative,” Jadallah notes. To illustrate this, the Najar Foundation show displays a 1940 postcard showing Stuttgart, which at the time had a number of Bauhaus buildings, by Gropius, Mies, Le Corbusier, and others. Whoever produced the postcard dismissively titled the town “Araberdorf,” or “Arab village”, and superimposed images of Arabs in traditional dress onto it. Verisimilitude is not the image’s strong point, but stereotypes are.

A few men seem to be in the midst of buying a carpet, while a young boy tugs at a camel to try. In the background, two rows of women in abayas inexplicably march in single file, and on the very right, two lions with extraordinary manes perch casually on the wall. Within Tel Aviv, however, the intrinsic Arab connections to modernism were played down. The Israelis associated Arabs with backward traditions, compared to their own forward-thinking modernism. "There were 4,000 Bauhaus buildings built in Tel Aviv between the 1920s and 40s, in what was then Mandate Palestine," says Jadallah.

Many of the architects behind Tel Aviv’s modernism were European, and particularly Jewish, transplants.

“Tel Aviv is known as the ‘White City’ because all of the 4,000 buildings were painted white,” says Jadallah, who is Palestinian. “But it is also because they wanted to be the city of the white architects, versus the brown, Arab architects.”

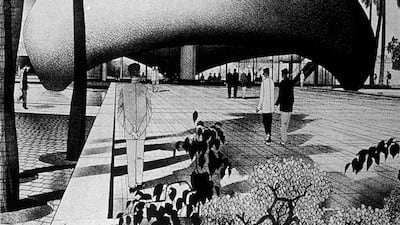

In addition to Tel Aviv, the show takes in other major projects in the Middle East, such as Gropius/TAC's designs in the 1950s for the campus of the University of Baghdad, which was to be built for 12,000 students on a 500-acre plot south of the city. But only a few elements were actually built: some lecture halls, a mosque and a high-rise tower, at the request of then-prime minister Abd Al-Karim Qasim. The mosque, though of extraordinary design, was only partially successful. Three arches supported the building's octagonal dome, so that the mosque was accessible on all sides. But the large windows allowed in so much noise that many found it unsuitable for prayer, and for other reasons it is no longer used as a religious site.

Jadallah also demonstrates how modernism appears in the UAE, in two buildings that TAC designed: the Cultural Foundation in Abu Dhabi and in the Inter-Continental Hotel on Sharjah's Corniche (now the Radisson Blu), which were both built in 1981. (Gropius died in 1969, but the collaboratively led TAC continued until the mid-1990s.)

The Arab flourishes of the Cultural Foundation, such as the blue tiled arches and geometric carving in the dark wooden doors, show how TAC operated in tandem with local architects. The level of regional adaptation – or on the flipside, modernist purity – differed from project to project, based on the goals of whomever commissioned the building. Sheikh Zayed, for example, is said to have ordered the tiles himself from Morocco.

For the Cultural Foundation, TAC worked with the Iraqi architect Hisham Ashkouri, who trained at the University of Baghdad and later studied under the modernist Louis I. Kahn. In his designs for the building, such as the plans for the outside fountain, one can clearly see again the overlap between traditional Arab forms and modernism.

A number of projects launched in the UAE, such as Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi's coming compendium of modernist architecture in Sharjah and the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, which is in its first year, are also investigating the history of modernism in the Gulf. Jadallah stresses that the significance of these buildings is not only in their aesthetic beauty, but in the role they played at the time.

“Modernist architecture from this period was a form of nation-building,” she says. “The UAE was trying to find a national identity, and that new identity came with modernist design. People are now waking up to how important this architecture is.”

Building Bauhaus is at the Jean-Paul Najar Foundation in Alserkal Avenue, Dubai until February 29, 2020