In a tiny, dimly lit workshop in the northern Indian city of Lucknow, Jalaluddeen Akhtar is hunched over a bag of ivory-hued buffalo bones of different shapes and sizes. He inspects each of them meticulously under a lens, assessing them for objects that could be crafted from them.

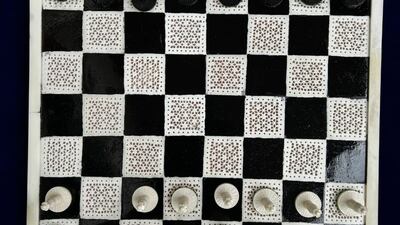

Soon, Akhtar’s work will begin. After days of cutting, cleaning, buffing and shaping – tasks that require remarkable hand-eye co-ordination, precision and skill – he will transform the unsightly bones into stunning marble-esque creations; exquisitely filigree lamps, finely crafted chessboards, knives, earrings, necklaces, hair clips, pens and more.

Sadly, Akhtar, 55, belongs to a vanishing breed of bone carvers in India, a craft that has been endangered by the onslaught of factory-manufactured decor items and plummeting demand.

The Indian government’s ban on ivory trade to rein in rampant poaching of elephants and smuggling dealt the final blow to the profession. Most bone carvers pivoted to wood carving or carpentry for survival, abandoning a legacy that has been part of India’s cultural heritage for centuries.

Back in the 16th and 17th centuries, bone carving flourished under the patronage of Mughal emperors who commissioned elaborate pieces to artisans to decorate their opulent palaces and forts or to give as gifts to other royals. Akhtar’s ancestors were one of them. “Today, we’re one among less than a handful of the remaining families who’re direct descendants of the royal bone carvers,” says the artist ruefully.

Be that as it may, Akhtar is determined to preserve his precious ancestral legacy by passing it on to the next generation. His son Akheel, 29, has been under his tutelage since he was 14. Even though he is now a qualified lawyer, the young man helps his father in his work. Akhtar recalls that he learnt bone carving from his uncle as a young boy and was “fascinated by the alchemy between the chisel, the bone and the artist”.

A devoted son, internet-savvy Akheel is leveraging the power of social media to help reach out to potential customers. However, while technology has helped bolster sales, it hasn’t helped Akhtar's workmanship.

“Very few machines or tools are available for us to work with. Except for some rudimentary ones, like a sawmill to cut the bones or a drill press for jaali [filigree] work, we do everything else by hand. We even make the bone cutter from umbrella sticks,” says Akhtar, the recipient of several state and national awards.

The artist says he sources the buffalo bones from local slaughterhouses. “Even the general belief is that we kill the buffaloes to acquire them,” he says. The bones have other uses as well, such as being used in powdered form as fertilisers.

Akhtar elaborates that a trained eye is required to select the right type of bones. The leg bones are best suited for his work as “they’re the strongest and broadest, which provides more wiggle room for intricate carving”.

After carving, the bones are scrubbed with bleach to get rid of their smell and yellow colour and then dried in the sun. Then begins the carving.

One of Akhtar’s most intricate carvings – for which he also bagged a national award from the Indian President in 2014 – was a 106cm lamp with exquisite jaali – a type of latticed design work. “It required months of labour and three of us to finish,” recalls the artist.

Another piece that Akhtar has just finished is a wall clock inlaid with such delicate patterns that a microscope is required to admire its finer details. It took 22 days of labour, 10 hours a day, to produce.

Akhtar currently has three full-time workers in his workshop, but freelancers are brought on when the work pressure gets intense or when large corporate orders come in during festivals like Diwali or Christmas.

“We’re increasingly getting a lot of work from offices for supplies of pen holders, paperweights, pen boxes, and other such items,” says the father of four. The size of the creations may vary from 1.5-metre room partitions to ear studs measuring just a few millimetres.

Recognising Akhtar’s talent, the government provides support by sending specialists to keep him abreast of current art and design trends. Students of the country’s premier fashion institute – the National Institute of Fashion Technology – visit him regularly for this purpose.

Over the last three decades, Akhtar has attracted clients from all over the world. Art lovers from India – Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Jaipur – regularly drop in to watch him at work. Once, an American couple who had read about his creations came to meet him. They also bought a ring box from Akhtar to store a precious possession – the engagement ring, which the man intended to propose with.

Akhtar says such interest in his work keeps him motivated. “My profession isn’t lucrative, but I owe a lot to it – my livelihood, respect and people’s love. What more can an artist desire?” he asks. But to survive, he adds, one needs patience and perseverance. “That’s why there are only a handful of us left in the trade. But whatever it is, bone carving is my bread and butter now.”

And occasionally jam, too. In 2014, Akhtar and Akheel were invited by the Indian government to participate in the international trade fair in Brazil. “We were in Rio de Janeiro for three days, staying in a five-star hotel, eating delicious food and exploring a beautiful country. We interacted with leading businessmen and sold a lot of our pieces. It was the best experience of my life,” recalls Akhtar with a grin.