Far up in the mountains of Mount Carmel within the borders of occupied Palestine, lies the heart of the country's Druze community.

The Druze are a traditionally insular people, who follow a roughly 1000-year-old faith with historical ties to Islam and have rarely caught the gaze of the filmmaking world. There are roughly two million worldwide, with around 150,000 living within Israel’s 1948 borders and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

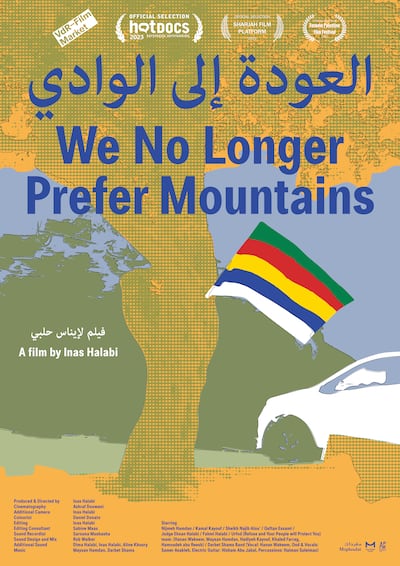

What do the Druze of Mount Carmel consider themselves? Are they Palestinian or Israeli? That depends on who you ask, as we learn in We No Longer Prefer Mountains, the debut feature by Palestinian artist and filmmaker Inas Halabi.

As her camera ascends the mountain and introduces us to the Druze villages of Daliyet Al Karmel and Isfiya, we find towns in tatters, full of divided residents in the midst of an existential crisis.

A seasoned visual artist, Halabi is ostensibly a strong follower of Masao Adachi’s idea of fukeiron, or landscape theory. Adachi posited that the truth of a place, its oppression and sociopolitical realities, can be found plainly in its most everyday landscapes.

Halabi spends much of the runtime in long sequences exploring the towns themselves, showing us street signs and tattered flags, crumbling infrastructure and repressive public notices. We wander through forests full of trees, some indigenous, some foreign and planted by 20th century colonists. We get to the edge of farmland that has been declared a state park, meaning that the Druze owners can no longer till on their own soil. We then go into the homes of the residents themselves, watching them clean their floors or cook their dinners.

And as time passes in the deliberately paced film, we begin to hear more from the people of the town, as they narrate their version of how things got to be the way they are today.

That is when the film becomes truly fascinating.

One resident explains that, back in the 1950s, the Druze leaders decided to start collaborating with the Israeli government, sending their young for compulsory military service. Over the years, the Druze schools were separated from Arab schools by the state, we’re told, and the children who attended new state-controlled schools came home to tell their parents they did not consider themselves Arab or Palestinian any longer. They considered themselves Druze Israeli, unlike their parents, and they resented being called anything else.

With time, the divide grew even greater and those who clung to their heritage and traditional identity found themselves increasingly separated from those who decided to assimilate.

Deep into the film, we hear at last from one of those voices, a man who works in the local court system. He explains that the Druze are a minority wherever they live and can only survive if they pledge allegiance to the powers that be, wherever they may be.

If there were a war with Lebanon, the man says, and he was face to face with his Druze brother on the other side, he would still choose to defend Israel and attack his brother, because that is the way things must be in his estimation. That is how he will keep his people safe.

But for the younger generation, things are getting more complicated. The controversial Nation-State Bill declared Israel the nation-state of the Jewish people and laid bare for many that the government did not believe ethnic minorities had equal rights to their home, which left the Druze in a difficult position.

At the end of the film, a group of young Druze play a song about the bill and the predicament it has put them in. Perhaps it is time to consider themselves Palestinian once again, they imply. Perhaps it is time to engage in some form of resistance, whether that’s refusing to serve in the military on an individual basis or something more organised.

Ultimately the film is another example of a truth of storytelling, of art and of journalism – dig into any niche, and no matter how far you zoom in, you’ll always feel that you’ve only scratched the surface.

That is the beauty, and the most glaring flaw, of the film. It’s hard to watch it without wishing that we could spend more time with these people and hear other voices. Perhaps we could meet some of the young people who are more sympathetic to the Israeli position, to get a better understanding of how they see themselves, rather than hear it from others.

And with a subject matter so rich and characters so compelling, the art film nature of it – the pacing and the long shots of just landscape – makes one wish that the film were easier to recommend to those who have less patience for such things, but that is also a request for a different film altogether.

But as an introduction into this world, there are many unforgettable moments. Even if you may feel bored at times, with moments that echo the quiet depictions of home life found in the work of Chantal Akerman, when you look back at having watched it, your mind will light up.

Boredom as a part of artistic appreciation, after all, is an underrated part of the process. We're too scared of being bored these days, but we shouldn't, as that's when we begin to think for ourselves.

Speaking as a fan of film, I crave more stories from this world, as I feel I have a lot left to learn. Speaking as a human, I hope these people find the justice they deserve. A quiet triumph.

We No Longer Prefer Mountains screens on February 1 at Reel Palestine in Dubai