On November 3, 1914, two British cruisers opened fire on the 17th-century fort guarding the western entrance to the Dardanelles at Seddülbahir. One shell found the ammunition dump and the 85 officers and men of the Turkish garrison who died in the explosion became the first casualties of the Ottoman Empire to fall in the First World War, which broke out in Europe 100 years ago on July 28.

Though the Ottoman army, under the direction of German military advisers, would fight like lions in defence of the Gallipoli peninsula and severely maul Anglo-Indian forces in Mesopotamia in 1915-16, the ultimate outcome was as inevitable as its consequences for the Middle East were far-reaching and catastrophic.

The First World War was the final nail in the coffin of the Ottoman Empire, the once-mighty 600-year-old Islamic state that at its height in the 16th century had dominated most of North Africa, the Middle East and Anatolia and expanded into Europe as far as the gates of Vienna.

In the west, the main focus in this centenary year of the start of the First World War is on the butchery of the trench warfare that characterised the conflict on the western front. But it can be argued persuasively that the greatest calamity of this “war to end all wars” was not the carnage on the battlefields of Europe but the way in which the Middle East was carved up by the victors, sowing the seeds of all that has blighted the region for the past 100 years and, judging by the current events in Gaza, will continue to blight it for the foreseeable future.

For evidence of this, one need look no further than the hashtag #SykesPicotOver, which trended on Twitter last month following the bulldozing of a section of Iraq’s northern border with Syria by members of the rampaging Islamic State militant group.

This symbolic act, seen in photographs released by the Islamic State and captioned “The destruction of Sykes-Picot”, reflected long-held resentment at the redrawing of the map of the Middle East in 1916 by the British and French diplomats Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. But were these mid-level bureaucrats, or even their imperial masters, really to blame for the final catastrophic collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and the consequent dismembering and repackaging of Ottoman vilayets into troubled and troubling countries such as Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and, eventually, Israel?

Dating the problems of the Middle East from 1918 is to start the story’s clock running too late. One hundred years after the first of 770,000 Ottoman troops and as many as 2.5 million of the empire’s civilians lost their lives in the First World War, it is worth remembering that, as cynical architects of their own downfall, the Turkish leadership was complicit in the calamitous map-making that followed.

When the Ottoman Empire went to war against Britain and France in 1914, from the perspective of the two allies it did so in defiance of all common sense and historical precedence.

Within living memory, both Britain and France had fought alongside the Ottoman Empire to prevent an expansionist Russia encroaching on its territories, and for the British especially the impact of the conflict remains embedded in the national psyche.

To this day, the bloody battles of the Crimean War are commemorated in pub and street names throughout the UK. Britain’s highest military honour, the Victoria Cross, introduced in 1856 to recognise conspicuous valour among British troops in the Crimean conflict, is still forged from the metal of Russian cannon captured at the siege of Sebastopol.

And yet in 1914, with the last British survivor of the suicidally courageous charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava in 1854 still alive, Britain and France, now fighting for their own survival in Europe, found themselves obliged by what they saw as Ottoman betrayal to commit badly needed forces to a new front in the Middle East.

In the view of the allies, the new Ottoman rulers had been conned by Germany, whose only interest lay in keeping British troops away from the European battlefields. In November 1914, days after the attack on Seddülbahir, a cartoon in the British satirical magazine Punch, accurately predicting the consequences of the empire’s ill-judged alliance, depicted Turkey as an artillery shell being rammed into the breach of a field gun by the German kaiser.

“Leave everything to me,” the German leader is saying. “All you’ve got to do is to explode.”

“Yes, I quite see that,” replies an anxious Turkey. “But where shall I be when it’s all over?”

In 1914, war with the Ottoman Empire was the last thing Britain wanted. Since the earliest days of the Raj, successive British governments had pursued the admittedly self-interested policy of preserving the Muslim Ottoman Empire as a barrier against incursion by various European rivals keen to help themselves to the bounty that was India.

On the eve of the First World War, this was still Britain’s position, as evidenced early in 1914 in a speech to the House of Commons by a man who would, ironically, go on to play a key part in the post-war dismembering of Ottoman lands. “The disappearance of the Ottoman Empire,” Sir Mark Sykes warned his fellow MPs, “must be the first step towards the disappearance of our own.”

Until almost the last moment, Sir Edward Grey, the long-serving British foreign secretary, hoped that Turkey could be kept out of the war. To that end, as he recalled in the second volume of his autobiography, published in 1925, “everything conceivable was done to make it easy and even profitable for Turkey to remain neutral”.

Grey recalled that for Lord Kitchener, Britain’s hero of the Sudan and, in 1914, secretary of state for war, it had been sufficient that “Britain must not be involved in war with Turkey till after the Indian troops had got through the Suez Canal”. But for Grey there were strategic as well as tactical considerations, driven home by “an Indian personage of very high position and influence in the Moslem [sic] world [who] came to see me [and] urged earnestly that Turkey should be kept out of the war”.

Grey’s visitor told him that “if we were at war with Turkey it might cause great trouble for Muslim British subjects and be a source of embarrassment both to them and to us. I replied that we all felt this, and desired not to be involved in war with Turkey.”

To that end, a joint promise was made to the Turks by Britain, France and Russia that “in any terms of peace at the end of the war her independence and integrity should be preserved”. Nothing, wrote Sir Edward, “was asked from her in return, no help, no facilities for the Allies, open or covert, nothing except that she should remain neutral”.

On the other hand, Grey remarked to Sir Francis Bertie, the British ambassador to France, on August 15, 1914, “if Turkey sided with Germany and Austria, and they were defeated, of course we could not answer for what might be taken from Turkey in Asia Minor”.

Unknown to Grey and the British government, almost two weeks earlier the Ottoman Empire had already signed a secret treaty with Germany. In the process, it had also signed its own death warrant, setting the scene for a post-war territorial free-for-all, the results of which are now being so brutally contested by the fighters of the Islamic State.

In the months and weeks leading up to the Ottoman Empire entering the war, internal upheaval and personal ambition lay at the heart of the Sublime Porte’s confused and ultimately disastrous diplomacy. A coup d’état in 1913 by the liberalising Committee of Union and Progress had seen power shift from the sultan to the dictatorial trio of the Three Pashas, Mehmed Talaat, Ismail Enver and Ahmed Djemal. Riven from the outset by mutual distrust, jostling for personal supremacy and perhaps more than a little dazzled by German gold, the three set about outmanoeuvring one another for political advantage while embarking on the dangerous game of playing one European power off against the other.

In the end, it was Enver, one of the leaders of the Young Turk revolution in 1908 and now the war minister, whose terrible miscalculations tipped Turkey off the tightrope of neutrality. Unlike some of his colleagues, he was not only convinced that Germany would win the war but also believed that, if Turkey shared in that victory, the Ottoman Empire might actually be able to expand into Russian territory – an ambition as counterintuitive in 1914 as it was delusional.

"The big worry preoccupying the Ottomans was that they knew Russian policymakers had discussed how to secure Constantinople, as they insisted on calling Istanbul, and the straits, for direct Russian rule," says Dr Eugene Rogan, professor of the modern history of the Middle East at the University of Oxford's faculty of Oriental studies and author of The Arabs: A History [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk].

This had been a long-standing Russian ambition, partly for historic, religious and cultural reasons, but mainly because to secure the straits and the Sea of Marmara beyond was to open year-round access to the world for Russian shipping from the Black Sea via the Mediterranean.

It was fear of this ambition, says Rogan, that drove the Ottomans “into a frenzy of trying to find an ally in the summer of 1914”. True, the British and French “would not enter an alliance with the Ottomans against their entente partner, Russia”. But all three powers had nevertheless offered to protect Turkey’s neutrality, which meant the decision to go to war at Germany’s side was unnecessary.

But Enver, as David Fromkin noted in A Peace to End All Peace [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk], his definitive 1989 account of the fall of the Ottoman Empire, "stood to benefit personally from the many opportunities to increase his fame and position that war at Germany's side would offer". Not for the first time, the fate of an empire hung on the ambitions and actions of a single man.

A “dashing figure” of “only limited ability”, Enver believed that in throwing in his lot with Germany “he was making an investment, when he was doing no more than placing a wager”. And it was a wager that he, and the Ottoman Empire, would lose.

The widely accepted version of the events of the summer of 1914 is that the Ottoman Empire was driven to war on the side of Germany because Winston Churchill, Britain’s first lord of the admiralty, outraged Turkish public opinion by seizing two battleships being built for Turkey in British shipyards.

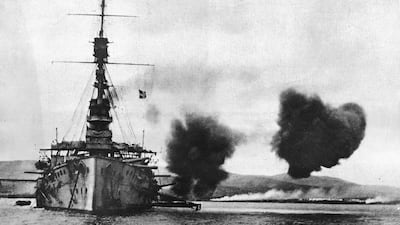

The Reshadieh and the Sultan Osman I were maritime monsters, imposingly armed ships of the new Dreadnought class that would pose a serious threat to Britain's navy should they fall into German hands. Accordingly, on July 31, 1914, three days before Germany declared war on France, and with British doubts about Turkish intentions deepening, the British government duly ordered that they be seized.

Even at the time, Churchill faced harsh criticism, in Britain and abroad, for the decision. History, however, has shown it to have been a prescient one. What no one knew until 1968, when a German historian stumbled on a cache of forgotten papers in his nation’s diplomatic archives, was that Enver had indeed promised the ships to Germany.

Right up to this point, says Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, an associate fellow on the Middle East North Africa programme at the independent policy institute Chatham House, the Turks could still have sided with Britain, or remained neutral – but the seizure of the ships played into the hands of the man determined to lead Turkey to war. "Enver Pasha really had a fight to persuade a lot of his colleagues that it was worth entering on the German side," says Coates Ulrichsen, author of The First World War in the Middle East, published last month [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk]. Though the presence of a German military mission in Istanbul was doubtless an important factor, "the anger in Turkey with Winston Churchill's decision really helped Enver in terms of swinging a large section of Ottoman opinion towards backing the Germans, which wasn't a universally popular position".

As part of the deal to entice Turkey into the war, Germany despatched the cruisers Goeben and Breslau on a flag-waving exercise to Istanbul. When they arrived, however, the Ottoman government, having privately failed to persuade Germany to let Turkey have the ships for its own navy, announced publicly that it had bought them.

As Fromkin noted, the frustrated German ambassador "advised Berlin there was no choice but to go along with the 'sale': to disavow it risked turning local sentiment violently around against the German cause". The Turks lacked the trained crews to operate the modern warships, and so the Germans, donning fezzes and Ottoman uniforms that fooled nobody, did it for them. At last the Turks were ready to come out from behind their pretence of neutrality and on October 28, without any declaration of war, the Turkish fleet with the Goeben and Breslau in the van sallied forth and attacked Russian ports and shipping in the Black Sea.

Something of the fury this provoked among the Allies radiates from Grey’s autobiography, written 11 years after the event. “Never was there a more wanton, gratuitous and unprovoked attack by one country upon another,” Grey fumed. “Russia had been genuinely anxious to avoid the complication of war with Turkey, and had joined in the offered guarantee … Turkey had a fair and genuine offer from the Allies and rejected it.” Turkey alone “was to blame for what followed”.

What followed, after four bloody years of war, was a dramatic and, in most cases, disastrous redrawing of the map of the Middle East, carved up between the victorious French and British with an imperious lack of understanding of cultural, tribal and religious nuances, with consequences that remain with us to this day.

Coates Ulrichsen believes the modern Middle East would doubtless have looked very different had the Ottomans held their nerve and kept out of the war – no Iraq, no Syria, no Israel, no Jordan and, perhaps, a different conclusion in the Arabian Peninsula to the nation-building ambitions of Ibn Saud: if things had gone differently, perhaps the world’s second-largest producer of oil today would have been Turkey.

“While we probably would still have seen a degree of postcolonial struggle against the Ottoman control of the Middle East, it probably wouldn’t have taken on the pronounced anti-western form that it did,” says Coates Ulrichsen.

“It would have been a struggle against the Ottomans rather than western powers, so it could definitely have resulted in a very different Middle East, both in terms of geopolitics and also in terms of the whole Arab-Israeli tension, which has really affected the region ever since.”

It is, he says, unfortunate that when people in the West think at all of the Middle East during the First World War, they think only of Gallipoli and, perhaps, of T E Lawrence, who helped to raise the Arab revolt in the Hejaz in 1916. And that, he says, “is a shame because there were huge campaigns that had long-lasting political results and in terms of the legacy of the war the Middle East is much more important than [what happened in] France”.

Worse, few in the region today appreciate the impact of the Ottoman Empire’s epoch-changing decision to side with Germany in 1914. “The irony is that because we have had so much else happen in the Middle East in the intervening century, there will be very few people even in the region who will look at the First World War with any sense of commemoration. Yet it is the decisions taken between 1914 and 1922 that continue to reverberate today.”

And what of Enver Pasha, the man whose ambition destroyed an empire? Within four years of the end of the war, he would pay with his life. He fled to Germany but was sentenced to death in absentia by a Turkish court martial for his part in dragging the Ottoman Empire to its doom. In 1921 he returned to action as an agent of Moscow in Turkestan, but switched sides and joined the anti-Soviet rebels Lenin had sent him to destroy. Eventually, he was tracked down and killed by Russian forces in 1922.

It was, according to one contemporary account, a mercifully quick death, brought about by a bullet to the heart. The suffering of the Middle East, however, continues to this day.

Jonathan Gornall is a regular contributor to The National.